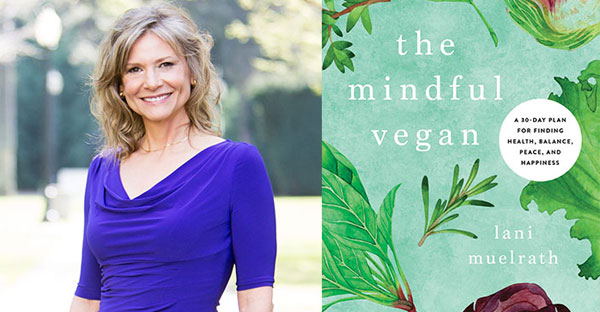

The following is an excerpt from The Mindful Vegan (October 2017, BenBella Books) by Lani Muelrath.

It is a moment I’ll never forget.

As I sat down to the midday meal, I was blindsided by a tightening in my chest, followed by a squeeze in my throat. I felt as if I could barely breathe. Accompanied by a knot in my stomach the size of Manhattan, I knew something monumental was taking place.

No, I wasn’t having a heart attack. But the impact of this event was no less far-reaching. For it was at this moment that a pivotal change took place in my life. It led to liberating me from a painful, troubled relationship with food. A relationship that had played itself out over decades of unsettled eating patterns, a tiresome preoccupation with dieting, constant self-criticism of my body, and the heartache of yo-yoing weight.

When one thought ends, right before the next thought begins, there is a tiny gap called “now.” Over time we learn to expand that gap.

—Spring Washam, meditation teacher

This moment heralded a dramatic new freedom, happiness, and peace with food that I celebrate to this day. Restoring the pure joy of eating, it ushered in an era of ease with food and my body that has proliferated into greater well-being in every area of my life. All of these shifts I can trace directly back to that instant nearly twenty-five years ago. One thing leveraged this dramatic change in my life: mindfulness meditation practice.

More than forty years ago, along with teaching yoga and adopting a vegetarian diet, I began a meditation practice. It wasn’t the mindfulness meditation practice I am sharing with you in this book. It was a different technique. Though my aspirations were all seventies spiritual, between you and me, I was looking for a solution to my food and weight problem, and I had hoped that meditation would do it.

I gave this technique my all, even traveling to remote regions of India several times. I would get up at three in the morning to sit for hours in meditation every day. Though I did learn how to sit still for long periods of time, and cultivated a bit of concentration, these practices never made a detectable dent in my food problem. As a matter of fact, I returned from one of those trips to India noticeably pudgier than when I left from pounding down handfuls of the roasted cashews, glucose biscuits, and endless buttery curries served at the ashram.

About ten years later, browsing through a bookstore while traveling, I came across a small book about mindfulness meditation. It explained how this practice—also known as Vipassana, or Insight, Meditation—could give us insight into our thoughts and emotions, help us simply be present with our feelings instead of trying to figure them out or escape them, and open up our capacity for equanimity.[1] I was immediately interested. Instinctively, I felt this might get to the root of my food problem. The book didn’t, however, include any how-to instructions. And I couldn’t find anything more about it. There were far fewer resources available at the time. The internet was still in the toddler stage, Amazon wasn’t born yet, and research was conducted via library card.

Returning home, I kept the book close and simultaneously dove right into completing my master’s degree and launching my TV show. Meanwhile, I continued to ponder why—though happily married, with gainful employment and a promising career blooming—I couldn’t seem to get a grip on this one area of my life: food and eating. My devotion to the meditation practice I had been doing gradually waned.

I dabbled in diets for another ten years, yet I kept circling back to the mindfulness book. Finally, I decided it was time to see if the benefits it seemed to offer were for me. I signed up for a retreat to learn mindfulness meditation. Located in the foothills of Yosemite National Park, it was a ten-day silent retreat.

That’s right. Silent. The purpose of the silence is to keep all outer distractions to a minimum. Just you and your body, thoughts, and emotions. Silence is where the curious gymnastics of our minds—from elaborate stories we spawn around our experiences to obsessive thinking loops to our particular avenues of escape from the vicissitudes of life, a constant parade of inner distractions—come into full view. Silence allows us to dive into this interior landscape—in a way that our usual day-to-day lives don’t. Mindfulness, together with willingness, kindness, and patience, allows us to be present with all of it in a way that directly defuses our troubles.

I took to the silence like a fish to water. It was actually great respite not to have to activate one’s personality with the usual social interactions. Yet as much as I relished the time “alone,” navigating my inner landscape brought its own set of challenges.

It was on day four of the retreat that the episode I opened this chapter with took place. I had just sat down to the midday meal, to be eaten in silence in keeping with retreat tradition, when I was overwhelmed by the experience that I described. One of the techniques of mindfulness practice is to be willing to look at physical sensations as they arise in the body—curiously, and without judgment or avoidance. So I turned my attention to the chest squeeze, the tightness in my throat, just to observe them for what they might have to teach me.

Immediately, I was flooded with insight. I realized how much tension and anxiety I had around food and eating. And I realized that I had probably been having this experience for years. I had exacerbated it with every new diet and underscored it with every feeling of guilt or other bad feelings about food, with each moment of admonition about eating and shame about my weight.

These emotions, I realized, had been there for a long, long time. I just hadn’t been aware of them. Instead, I had been playing out stress with another batch of cookie dough or preoccupation about the next diet. Inner discomforts had, for me, rallied into what had become an obsession—for when I wasn’t fixated on how I might conjure up a more dramatic weight-loss project, I was getting caught up in food cravings. Mindfulness practice was now giving me specific tools with which to address all of it. This insightful moment had two predominant qualities. I felt sorrow as I thought how sad it was that I had been having this experience for so many years—decades even. At the same time, it was a light-filled, expansive moment because of the insight I experienced around my food and eating problem.

Instantly, I felt a great flood of compassion for myself. Instead of living on autopilot and reactivity with my discomforts, I simply started choosing more and more often to be willing to be with what was present in the moment. This experience officially opened the world of mindfulness to me. It gave me firsthand experience of the transformation that can be experienced by being fully present and how the experience can change someone in an instant. Once you know, you can’t not. Looking back, the more I learn about myself, the more I believe I was probably feeling those tensions and anxieties much of the time, even outside of mealtimes. I simply never had the courage—even more, the basic tools—to realize and face them. All this time, I’d been thinking it was all about the food. But that was just part of the problem. Eating just happened to be the highly charged water I was swimming in at the moment the insight came.

I began to see past the promise of the cookie dough—or whatever form it might take on any particular day. Not out of punitiveness, or with willpower, but out of realizing that the sanctuary I sought in food was false, empty. With mindfulness practice I began to see past this agent of transitory asylum to the pain and confusion that always followed. This came as a natural outgrowth, organically emerging from the mindful experience. Looking clearly at our mental and emotional landscape, along with the physical sensations that are part of our moment-to-moment experience, reveals more to us about our experience than we can imagine. It is really quite remarkable that something so simple as being mindfully present with these phenomena can have such profound effect on our ability to find our way through obstacles that are so often hidden from view.

In that moment of insight at the retreat, I realized that focusing on the food was simply skirting the issue. I made the decision to abandon dieting altogether and travel the path of mindfulness. If the door to navigating this longtime obstacle could be so immediately unlocked and opened, what else might I discover that would illuminate the pathway and lighten my load, if I were willing to investigate?

From that point on, things between me and food changed. I stopped thinking of myself as some kind of food addict or compulsive eater. I stopped repeatedly trying to eat less to shed some pounds, in favor of reconnecting with my hunger and fullness signals—the connection with which is essential to eating mindfully. Chronically cutting back muddies our true hunger and fullness indicators, causes overeating, and is the single biggest driving factor behind food blowouts and binges. Previously, I could overeat with the best of them. But I never again had one binge incident.

While I worked briefly with a coach to help me navigate the uncertainty of letting go of dieting as I knew it, it is the tools of mindfulness meditation practice that walked me through the enormous wall of fear that letting go of these controls around food, eating, and weight presented, and opened the door to unprecedented freedom. Micromanaging and analyzing every bite and obsessing over body weight and size mask underlying stress, anxiety, and not-good-enough syndrome. And heaven knows it’s reinforced by our culture and cemented by the diet industry. It’s one thing to read about these problems and associations and an entirely different thing to steer right through the middle of the unsettling mess. The discomforts of the loss of the familiar, even though the familiar may be painful, can be disquieting as you let go of outmoded illusions of control and move into new, uncharted territory. Without a way to navigate the seas, you continue to spin in the whirlpool.

As I continued to practice mindfulness meditation, moments of quiet, glimpses into a peaceful mind, and the growing ability to let go of the grip of obsessive thinking edified my practice. Obsessive thinking of any kind is a place we seek refuge from our restlessness and fears. We might feel anxious and seek refuge in food, other substances, or surfing the internet. We might feel insecure and seek refuge in a relentless drive for recognition or monetary success. We might feel shame and obsessively enslave ourselves to the pursuit of body perfection. Yet all false refuges respond to an interested and caring attention. We can listen to the energies behind our obsessive thinking, respond to what needs attention, and spend less and less time removed from the presence that nurtures our lives. We experience more and more often the freeing qualities of simply being present.

Over the years, my relationship to food moved in a couple of directions. For one, as I became more consciously connected with the problems perpetuated by dairy—the last vestiges of animal products in my diet—I moved from vegetarian to vegan. For several years, on the way to the school where I taught, I would drive through rolling green hills in which dairy cows grazed. As I passed them, I would sink down in my car seat with apologies in my heart and on my lips. “I’m sorry!” I would whisper. Off and on inspired to make the switch to vegan, I would come and go from eating yogurt and cheese. The awareness of inner dissonance grew with my mindfulness practice. Finally, one day, realization of the unsettling inner state I was perpetuating pushed dairy off my plate. What a difference in lightness of heart and integrity the driving-to-work experience became.

I remain watchful and alert to the many faces that obsessions around food and eating can present. I constantly see them play themselves out in people who come to me for help with their weight, food, and eating problems. Often it shows up as anxiety channeled into micromanagement of even the healthiest of foods. Overanalyzing and replaying one plant-based food plan after another, conflicted about the one right answer—they are unaware that, a large part of the time, the obsession itself is holding them back. We deal with our disquieting states and worries by hiding behind the skirts of one preoccupation or another— or one after another.

With mindfulness, you are cultivating a state of being that allows all the gifts of mindfulness to unfold in your experience. You don’t seek peace of mind; you create the conditions in which peace of mind can take place. You don’t seek to be free of mindless eating; you foster a state of mindfulness that sheds mindless eating like a snake sheds a skin. Rather than seeking just the right thing to say, you restore equanimity, compassion, and heart, bringing a kinder, clearer presence to each conversation and encounter.

Copyright 2024 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.