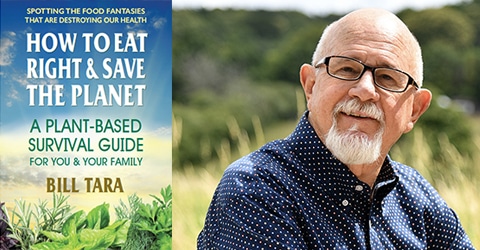

The following is an excerpt from How to Eat Right & Save the Planet (January 2020, Square One Press) by Bill Tara.

The biosphere is a delicate and dynamic system of energy, organic matter, and inorganic matter. When we disrupt any part of it, the results ripple out and have far-reaching effects, often seemingly unrelated to their source. Human activity is one of those seemingly unrelated sources for most of the problems in the modern world. War, degenerative disease, the mass extinction of animal species, and the pollution of the oceans all trace back to us.

We have failed miserably to create a way of living that produces a healthy life for ourselves and the world at large. We need a healthy human ecology, a way of living that assures future generations an opportunity to grow and prosper. We need to do it now. We are running out of time.

In 1943, the famed psychologist Abraham Maslow published a paper called “A Theory of Human Motivation.” This groundbreaking work laid the foundations for the next three decades of developmental psychology. Maslow was looking for defining principles of human happiness, for what makes us feel complete. His conclusions were simple, yet profound.

In identifying what he called a hierarchy of needs, he established that we must meet our basic physical requirements before addressing other areas of fulfillment and joy. The first level of need includes air, food, water, shelter, warmth, sex, and sleep. When these needs are attained, we seek the second level, safety, which includes protection from the elements, security, order, stability, and freedom from fear. Our desires for love, esteem, self-expression, creativity, and the realization of our full potential rest on the foundation of these first two levels. If they are not met, we risk living with constant anxiety, stress, and ill health. It would be fair to say that those first two levels are really talking about health.

When we look at the list of needs for healthy human life, it is easy to see that we are painting ourselves into a corner. Those factors of clean water, healthy food, reliable shelter, order, and freedom of fear are not available to an increasing percentage of the population. Problems that were once only seen to be common in poor nations now inhabit the streets of affluent society.

The number of people living in urban areas exceeded 50% of the world’s population for the first time in 2014.[1] It looks like it will be 70% by 2050. The WHO lists resulting health challenges such as poor water quality, environmental pollutants, violence and injury, increased noncommunicable diseases (cardiovascular diseases, cancers, diabetes, and chronic respiratory diseases), unhealthy diets and physical inactivity, harmful use of alcohol, and increased exposure to disease outbreaks. In an unintended irony, one of the few advantages of urban living is listed as access to better health care.

Our Relationship With Nature

When I started studying food and nutrition over 50 years ago, I was intrigued by the connection between what I was eating and the environment. I discovered that many of the foods that had questionable or negative effects on health also had an adverse environmental impact. This should not have surprised me.

We do not need new products to create a wholesome way of eating. What we need is a new way of looking at the whole issue of food and health. We need a user-friendly, common-sense approach to understanding food that is healthy and sustainable for society and the environment. To accomplish this requires us to question everything we have been told about nutrition and to review some very basic questions about the role of food in our life and in our culture. Much of the Eastern philosophy I have read has pointed to a particular relationship between the individual and nature.

The word health originates in old English and means “to be complete.” Food is certainly an important part of being whole—being connected. To be healthy, we eat food that allows us to operate at our full potential. That potential includes the sensitivity and capacity to adapt to environmental change. Health enables us to nurture the bond between nature and ourselves. Ecology is a central theme of the ancient systems of understanding food.

Ecology is rarely acknowledged when discussing nutrition, and yet it is central to understanding our food choices and how different foods affect us. These effects are both direct and indirect. Rachel Carson, the American biologist, author of The Silent Spring,[2] and the accepted mother of modern ecology, put it this way:

If we have been slow to develop the general concepts of ecology and conservation, we have been even more tardy in recognizing the facts of the ecology and conservation of man himself. We may hope that this will be the next major phase in the development of biology. Here and there awareness is growing that man, far from being the overlord of all creation, is himself part of nature, subject to the same cosmic forces that control all other life. Man’s future welfare and probably even his survival depend upon his learning to live in harmony, rather than in combat, with these forces.

This view of our relationship with nature is more crucial now than ever. Carson’s vision of an evolution in biological science that unifies human life with the environment has been steadily sidelined. If man is “a part of nature, subject to the same cosmic forces that control all other life,” then natural law exists for us, as well as for every other creature, plant, and aspect of the planet. If we do not learn to cooperate with the laws of nature, we will harm ourselves. We don’t need an environmental degree to understand natural law.

We tend to view the world we live in—and often all other life except domestic animals—as the “other.” Our belief in human supremacy (often referred to as anthropocentric thinking) allows us to place ourselves at the center of the universe. We view our uniqueness as a sign of separation from the rest of life that swirls around us and within us.

The belief that we are superior to and separate from other life forms permits us to use the natural world according to our desires and whims. As we pull away from any physical interaction with nature, we fortify those mythologies that lie at the foundation of our most harmful behaviors.

In ecological studies, there are several kinds of relationships between an organism and its environment. The first thing we need to know about any new creature we discover is how it procreates and what it eats. These are the driving forces of evolution; they dictate physical form, function, and most behavior.

What does our casual disregard for the environment say about us?

One class of relationship is called commensalism, from the Latin “to eat at the same table.” These are relationships where one organism gains benefits and the other is not affected. Another type of relationship is mutualism, where both organisms benefit. In sharp contrast is the parasitism relationship, where one organism benefits while the other is harmed. Creating a commensal relationship with the planet is primary for humanity. Our well-being is interdependent with the well-being of the planet. It is also the key to a comprehensive vision of human nutrition.

Planet Earth is host to human life. The natural world makes human life possible. Our current relationship with the planet is almost entirely parasitic. The famous British naturalist David Attenborough recently referred to humanity as “a plague on the planet.”[4] The chemist and co-creator of the Gaia Theory, James Lovelock, said that humans are “too stupid to prevent climate change.” What does our casual disregard for the environment say about us?

Brave New World (With New ‘Meat’ Products)

We like to imagine that our relationship with nature is a kind of benign mutualism, one where we take from nature in exchange for nature having the pleasure of our company. The conundrum we face is that our whole economy is based on endless consumption; we are eating up the environment. But as economist E.F Schumacher said, “Infinite growth of material consumption in a finite world is an impossibility.”

Protein provides a good example of a human obsession becoming an environmental problem. Obtaining adequate protein in our diet is easy. A diet with a variety of grains, beans, vegetables, nuts, and seeds provides more than sufficient protein for health and vitality.

Increasing numbers of people understand that meat is not a good food choice. Some avoid meat for ethical reasons (abuse and killing of animals), some because of environmental impact, and some due to health concerns. Changing to a vegan diet affects social and personal habits. What if you understand all that but like the taste of meat? What if you like the texture of meat? Don’t worry, a solution is at hand. Food science is on the way to your door with fake “meaty stuff.”

Yes, we can make and sell you soya hot dogs, lunch meats, imitation steaks, and burgers. They can taste like beef, chicken, or pork. These products are perhaps culturally fun, but they do not address the issues of good nutrition. Soy is difficult to digest; that is why the people of Asia fermented it. We have to use additives, excessive salt, and extensive processing to get the meaty taste that mimics flesh, all because we love to indulge our senses.

The young entrepreneur who started Beyond Meat outlined his idea in an interview with Business Insider magazine.[6]

Meat is well understood in terms of its core parts, as well as its architecture. Meat is basically five things: amino acids, lipids, and water, plus some trace minerals and trace carbohydrates. These are all things that are abundant in non-animal sources and in plants.

Here we have the idea that “food is a chemical delivery system.” This is part of the problem. Food is a more complex issue. It involves cultural, environmental, and even emotional issues. Any serious conversation about healthy food must address all of these. The alternative is simply handing over the creation of food back to corporations and cutting nature out of the loop. So-called healthy products that are animal free are a bonanza for the canny investor. What society eats will once again be in the hands of those who produced the most unhealthy diet in history.

I will lose many of my vegan friends here who think that fake meat is the best thing since sliced bread. Fake meat is being marketed as a solution to “the meat problem,” but we don’t have a meat problem. We have a human problem. According to one study by Food Research International, manufactured faux meat uses an equal amount of energy to produce as meat products.[7]

Fake meat and highly processed imitation dairy products represent clever marketing but do not really offer a healthy alternative. They are focused on deceiving the taste buds as well as the desire for “doing the right thing.” These products are usually filled with processed oils, soya by-products, food additives, and excessive salt. The wave of the future must lie in a whole food, plant-based diet that takes food preparation out of the factory and into the kitchen. It is the only way to create a healthy planet for both human and non-human life.

This was an excerpt from How to Eat Right & Save the Planet (January 2020, Square One Press) by Bill Tara.

References

- World Health Organization, Global Health Observatory data

- Silent Spring (Penguin Modern Classics), original publication 1962

- “Essay on the Biological Sciences” in Good Reading (1958)

- The Guardian, September 10, 2013

- The Guardian, March 29, 2010

- Business Insider, August 15, 2015

- Environmental Impact of four meals with different protein sources, Food Research International, Volume 43, Issue 7, August 2010

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits