Earlier this year, a US federal judge upheld an “ag-gag” law in Iowa that prohibits unauthorized access to private property for the purpose of recording footage inside animal agriculture facilities.[1] To many, this decision may seem like a minor issue of property rights. But its implications reach far deeper, striking at the core of transparency, food safety, workers’ rights, and even freedom of speech.

To understand why laws like this matter, it helps to look back more than a century, to a moment when another form of investigative exposure changed America forever.

In 1906, journalist and novelist Upton Sinclair published The Jungle, a groundbreaking work of muckraking journalism that revealed the horrific conditions inside Chicago’s meatpacking industry. Sinclair originally set out to document the exploitation of immigrant laborers crushed under the weight of poverty, long hours, and corporate greed. But what truly shocked the public were his vivid descriptions of filth and contamination in meat production: rats ground into sausage, spoiled meat repackaged and sold, workers falling into rendering vats.

Americans were horrified not so much by the suffering of workers but by the realization that they themselves were consuming tainted meat. Outrage spread quickly across the nation, prompting President Theodore Roosevelt to order a federal investigation. Within months, Congress passed two landmark reforms: the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. These laws became the foundation for modern food safety and led to the creation of what would become the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Reflecting on the unintended impact of his work, Sinclair famously wrote, “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach.” Over a century later, the dynamics Sinclair exposed are repeating in a different form, but this time, laws are being used to prevent the public from ever seeing what goes on inside industrial agriculture.

“If slaughterhouses had glass walls, everyone would be a vegetarian.” – Paul McCartney

What Are Ag-Gag Laws?

“Ag-gag” laws are state-level statutes designed to suppress whistleblowing and investigative journalism related to animal agriculture. They typically take three main forms:

- Prohibiting photography, video recording, or document collection at animal agriculture facilities without the owner’s consent.

- Criminalizing misrepresentation—for example, applying for a job under false pretenses in order to record evidence of abuse or unsafe practices.

- Requiring the immediate reporting of animal cruelty, often within an unrealistically short time frame, making it impossible to compile meaningful evidence or build a case.

At face value, these laws are framed as protecting farmers’ property rights and biosecurity. But in practice, they serve a different purpose: shielding industrial agriculture from public scrutiny.

Timeline of Ag-Gag Laws in the US[2]

- 1990–1991: First wave—Kansas (1990), Montana (1991), and North Dakota (1991) pass the first ag-gag laws, criminalizing undercover documentation on farms.

- 2002: Alabama enacts a similar statute restricting access to animal facilities under false pretenses.

- 2011–2014: Second wave—Iowa, Utah, Missouri, Idaho, and Wyoming pass modern ag-gag laws following a surge of undercover investigations.

- 2015–2019: Legal pushback—Federal courts strike down laws in Idaho (2015), Utah (2017), Wyoming (2018), Iowa (2019), and Kansas (2020) as unconstitutional.

- 2016–2021: North Carolina and Arkansas enact new versions; several face ongoing constitutional challenges.

- 2023–2024: Iowa passes revised versions partly upheld in court; Kentucky introduces new legislation.

- Today: Six states (Alabama, Arkansas, Iowa, Missouri, Montana, and North Dakota) still have active ag-gag laws, though most have faced or continue to face legal scrutiny.

Over the past decade, several US states have enacted or attempted to enforce ag-gag laws. Many of these have been struck down as unconstitutional under the First Amendment, thanks to challenges from journalists, advocacy groups, and civil liberties organizations. Courts in Idaho, Utah, Kansas, and North Carolina, for instance, have ruled that these laws unlawfully restrict free speech and public access to information.

Yet six states still have active ag-gag laws that have not been overturned: Alabama, Iowa, Missouri, Montana, North Dakota, and Texas. Two of these, North Dakota and Montana, were among the first to introduce such laws decades ago, laying the groundwork for others to follow. With the successful lawsuit protecting the ag-gag law in Iowa, we can expect animal agribusinesses in other states to follow similar legal pathways to prevent further public scrutiny.

The Cost of Silence

By preventing journalists, activists, and even employees from documenting conditions inside facilities, ag-gag laws don’t just keep consumers in the dark about animal cruelty. They also compromise food safety, conceal environmental harms, and silence workers who might otherwise expose violations of labor or safety standards. This obfuscation further enables meat-heavy diets, which are responsible for pushing us beyond 7 of the 9 planetary boundaries.

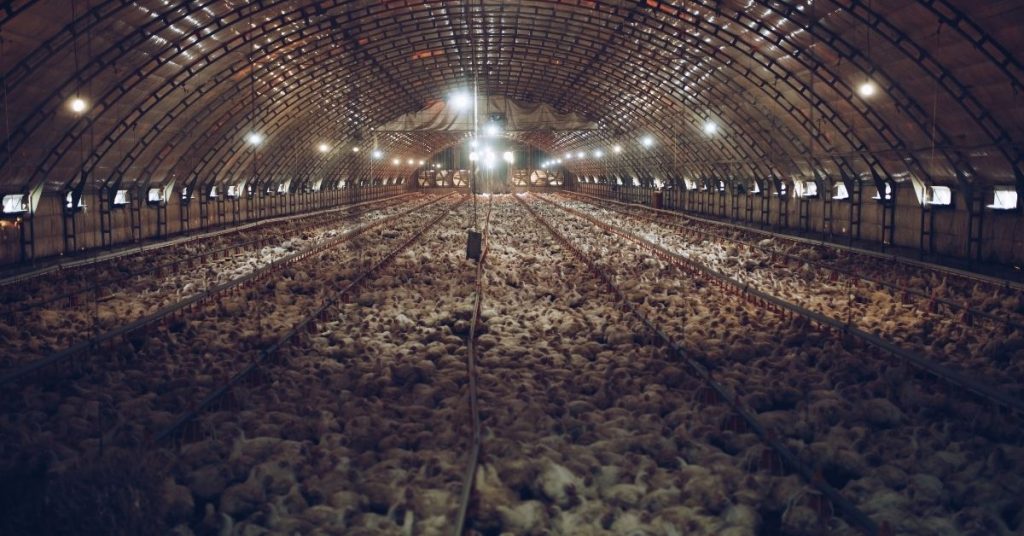

Many of the most significant food safety reforms and public awareness campaigns in recent decades began with undercover investigations showing cows too sick to walk being sent to slaughter, or chickens crammed into filthy, overcrowded sheds. These investigations not only revealed cruelty but also highlighted the unsanitary conditions that can spread disease and contamination through the food supply.

Without such evidence, there is no public pressure, no accountability, and no reform. This is especially important given that nearly 70 percent of US consumers say animal welfare drives their buying choices, and nearly the same share demand companies enforce welfare standards consistently across their supply chains.[3]

In effect, ag-gag laws protect not only the interests of agribusiness but also the secrecy that allows abusive and dangerously unsustainable practices to persist. They punish those who challenge the status quo with facts and footage, the very tools of democracy and journalism.

In an age when information can spread globally in seconds, the persistence of ag-gag laws is a step backward toward secrecy rather than accountability. These laws not only insulate powerful industries from criticism but also undermine the very principle that once transformed America’s food system: the public’s right to know.

If Sinclair were alive today, he might never make it past the slaughterhouse gates. Instead of writing The Jungle and sparking reform, he would likely face criminal charges.

More than a century ago, public outrage led to the creation of modern food safety laws. Today, similar outrage is being stifled before it can begin. This intentional stifling of the truth is keeping us in the dark and allowing for some of the most inhumane and environmentally disastrous practices to persist, all without our tacit support.

References

- Federal judge upholds Iowa ag-gag law in constitutional challenge. Husch Blackwell. Accessed online October 18, 2025. https://www.huschblackwell.com/newsandinsights/federal-judge-upholds-iowa-ag-gag-law-in-constitutional-challenge

- What is ag-gag legislation? ASPCA. Accessed online October 18, 2025. https://www.aspca.org/improving-laws-animals/public-policy/what-ag-gag-legislation

- Nearly 70% of Americans say animal wellness plays an important role in purchasing decisions. NSF. February 14, 2024. https://www.nsf.org/news/nsf-reveals-americans-say-animal-wellness-important-role-purchasing-decisions

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits