In recent years, the phrase environmental tipping points has moved from scientific journals into public conversation. It now appears in climate reports, headlines, and policy debates, most recently and comprehensively in The Global Tipping Points Report for 2025.[1] Yet tipping points are not abstract metaphors or tools of alarm. They describe real, measurable processes within the earth’s systems, processes that fundamentally change how the planet functions once certain thresholds are crossed. Understanding them is essential for making sense of the moment we are in, and for recognizing why food systems sit at the center of the climate challenge rather than at its margins.

Climate change is often imagined as a slow, linear process: temperatures rise gradually, impacts accumulate steadily, and societies adapt incrementally. Tipping points disrupt this narrative. They can be described as nonlinear, whereby long periods of apparent stability give way to sudden and potentially irreversible shifts. Ice sheets do not simply melt evenly—they reach a point after which they can collapse. Forests do not decline smoothly; instead, they can rapidly flip from carbon sinks to carbon sources. After decades of apparently quiet stress, ocean systems can weaken abruptly. In these systems, small additional pressures can trigger disproportionate effects, and reversing those pressures does not necessarily restore the original state.

This is what scientists mean by an environmental tipping point—a threshold beyond which a system reorganizes itself into a new condition. Once crossed, feedback loops take over. For example, thawing permafrost releases methane, which accelerates warming and thus causes more permafrost to thaw. Forest loss reduces rainfall, increasing drought, which leads to further forest dieback. These self-reinforcing dynamics compress the timelines by which we might respond. This is why waiting for the damage to become obvious is so dangerous: by the time tipping points are passed, our options for addressing the damage have already narrowed.

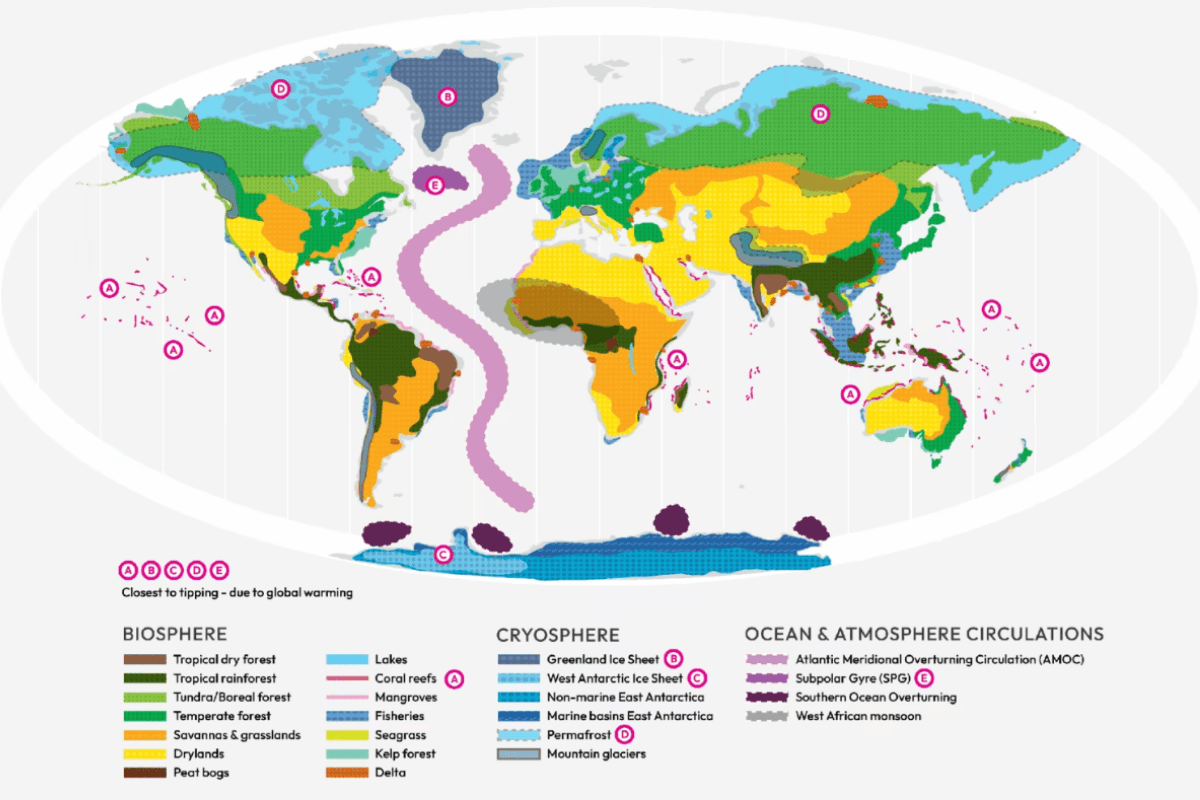

Over the past two decades, scientists have identified multiple large-scale tipping points:

Source: Global Tipping Points Report 2025.[1]

Crucially, these systems do not exist in isolation. Ice melt influences ocean circulation, which affects weather patterns. Forest loss alters rainfall far beyond regional boundaries. Ocean warming undermines marine ecosystems while reshaping fisheries and coastal livelihoods. When one tipping point is crossed, it can increase the likelihood of others following. This is what scientists call cascading tipping points: a chain reaction that amplifies risk across the planet.

These are no longer theoretical concerns. The systems described above are already showing early warning signs. Ice sheets are losing mass faster than previously projected.[8] Parts of the Amazon now emit more carbon than they absorb.[9] Permafrost temperatures are rising.[10] And coral bleaching events that once occurred once in a generation now happen every few years.[11] In most cases, scientists cannot say with certainty whether a tipping point has already been crossed or is still approaching. But this uncertainty does not offer reassurance. Because tipping points involve irreversibility on human timescales, uncertainty increases risk rather than reducing it. Precaution matters precisely because recovery is limited once thresholds are breached.

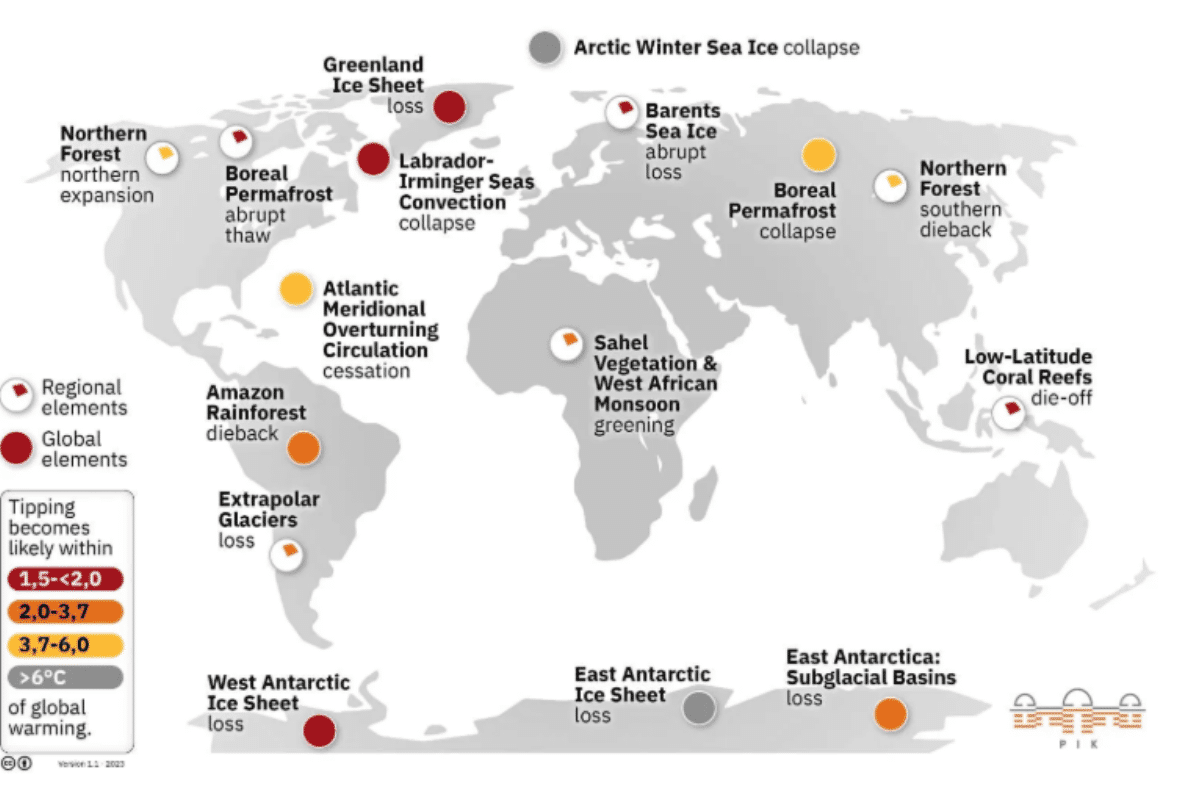

To understand what lies ahead, it helps to think in terms of temperature thresholds rather than distant dates. At around 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming above preindustrial levels, several tipping points move into high-risk territory, including widespread coral reef collapse and increasing instability in polar ice sheets. At 2.0 degrees Celsius, risks multiply and compound. The likelihood of Amazon dieback, large-scale ice sheet loss, and permafrost feedback rises sharply, and interactions between tipping elements become more pronounced. At 2.5 degrees Celsius and beyond, earth system stability becomes increasingly difficult to maintain, as feedback loops dominate and we lose our ability to steer long-term outcomes.

Source: Climate Tipping Points[12]

These temperature ranges are not precise switches that flip systems on or off. They represent zones of escalating danger. Perhaps most importantly, warming today can lock in future change even if impacts unfold decades later. By the time consequences are fully visible, the underlying commitments may already be irreversible.

For humanity, the implications are profound. Tipping points threaten the environmental conditions that support food production, water availability, and stable livelihoods. Shifting rainfall patterns, extreme heat, ecosystem collapse, and sea-level rise would undermine food security and strain societies. These consequences would affect different populations unevenly; often, those who have contributed the least to these problems will bear the brunt of the impact. As environmental stability erodes, the risks of displacement, conflict, and economic shocks rise.

While adaptation will be essential, it is not a solution on its own. No amount of adaptation can refreeze thawed permafrost, rebuild collapsed ice sheets, or revive dead coral reefs. Preventing the most dangerous outcomes requires rapid mitigation. That means reducing the pressures pushing earth systems toward their thresholds in the first place.

This is where food systems can play a big role. Avoiding tipping points demands speed, and food system change is one of the fastest levers available. Unlike energy infrastructure, which can take decades to replace, food demand can shift quickly. Agriculture already occupies nearly half of the planet’s habitable land, drives deforestation, emits large quantities of greenhouse gases, and shapes water cycles and biodiversity at a planetary scale.

Through land use change, especially deforestation for grazing and animal feed, food production weakens ecosystems that regulate climate and rainfall. Livestock emissions accelerate warming, pushing multiple tipping elements closer to instability. Industrial agriculture degrades soils, pollutes waterways with excess nutrients, and places immense pressure on freshwater systems. These forces combine, amplifying warming while eroding the natural buffers that might otherwise slow it. While livestock occupies 80 percent of agricultural land, it only provides 17 percent of the world’s calorie supply.[13] Within this inefficiency lies tremendous opportunity.

The relationship between food and tipping points is stark. Deforestation for cattle and soy feed accelerates Amazon dieback, while plant-based diets and reduced beef demand ease pressure on forests and open space for rewilding. Methane emissions from livestock contribute to warming that accelerates permafrost thaw, while dietary shifts can rapidly reduce those emissions. Nutrient runoff and ocean warming drive coral collapse, while changes in farming practices and reduced emissions help protect marine ecosystems. Feed-crop irrigation strains freshwater systems, while more plant-forward agriculture uses land and water far more efficiently. Monocropping and habitat conversion drive biodiversity loss, while agroecology and diversified plant-based systems restore resilience.

As mentioned already, food systems can change faster than transportation or energy systems. Cultural norms around diet are already shifting, especially among younger generations. Plant-based options are expanding rapidly; innovation is accelerating; and policy, markets, and consumer behavior are beginning to align. This creates the possibility of a self-reinforcing transition in which sustainable diets become the default rather than the exception, rapidly and simultaneously reducing pressure on climate, land, water, and biodiversity.

Environmental tipping points are not abstract future risks. They describe the boundaries within which human societies can thrive. Every day, food choices shape land use, emissions, and ecosystems. They are among the most immediate ways societies influence the stability of the earth system. The task ahead is not perfection but momentum. Preventing the worst outcomes depends on what we normalize now, what we grow, what we eat, and which food systems we choose to support before the next threshold is crossed.

Copyright 2025 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.