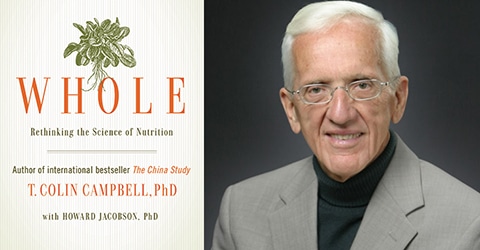

The following is an excerpt from Whole: Rethinking the Science of Nutrition (BenBella Books) by T. Colin Campbell, PhD and Howard Jacobson, PhD.

“What we do to ourselves, we do to the earth.” — Chief Seattle

Every July 4th weekend, my adopted home town of Durham, North Carolina, hosts a wonderful crafts and music festival to raise money to preserve a local river. Bands come from all over the country to share their music in a beautiful state park. Vendors sell handmade jewelry, pottery, and clothing. Activists and environmentalists hold forth on solar energy, river cleanup projects, opposition to nuclear facilities, and various other causes. Every napkin, spoon, plate, and cup given out by food vendors is 100 percent biodegradable. In short, you couldn’t hope to find a more environmentally conscious gathering.

Except for one thing: most of the food that festival goers shovel into their bodies. Deep-fried funnel cakes slathered in synthetic syrup and confectioners’ sugar. Giant turkey drumsticks, hamburgers, chicken breasts, and corn dogs sourced from factory farms that pump hormones and antibiotics into their products. French fries submerged in fryers of genetically modified cooking oil. While we know that littering and polluting rivers and streams is bad, somehow we’ve accepted that polluting our own bodies is okay, as if what we eat has no impact on the rest of the environment.

I know many environmentalists whose commitment is manifest and commendable, but stops at their lips. It’s understandable; many of our favorite “foods” (or, more properly, food-like items) are highly addictive. And our relationship with food is far more emotionally fraught than, say, our relationship with incandescent light bulbs or plastic shopping bags. But even these far-seeing and far-thinking activists are wearing reductionist blinders if they cannot see that their personal food choices matter at least as much as—and I would argue considerably more than—recycling and using energy-efficient light bulbs.

I began this chapter with a quote, attributed to Chief Seattle: “Whatever we do to the earth, we do to ourselves.” You may have come across it, or some variation on it, before; it’s often invoked by environmentalists to remind us that we can’t clear-cut our forests, pollute our water, and spew toxins into our air without ultimately harming ourselves. But what’s less obvious is that the reverse is equally true: what we eat has a huge impact on our environment. Specifically, our high consumption of animal-based foods contributes to environmental problems like soil loss, groundwater contamination, deforestation, fossil fuel use, and depletion of deep aquifers.

A Cornell University colleague of mine, Dr. David Pimentel, has documented many ways that our system of livestock production wastes precious resources and destroys the environment. He estimates that animal-based food requires about five to fifty times more land and water resources than the same number of calories of plant-based food (depending on various considerations, including animal species and whether the animal is pasture fed). In a world where human hunger is endemic, this inefficient use of resources is a tragedy.

Among Dr. Pimentel’s findings:

- Animal protein production requires eight times as much fossil fuel as plant protein.

- The livestock population of the United States consumes five times as much grain (which is not even their natural diet) as the country’s entire human population.

- A United Nations–sponsored workshop of about 200 experts concluded that 80 percent of deforestation in the tropics is attributable to the creation of new farmland, the majority of which is used for livestock grazing and feed.

So we’ve got a host of interconnected problems that all stem from our addiction to an animal-protein-based diet. Simply put, our industrial system of animal production is unsustainable. We’re using up our natural resources, such as fresh water and healthy soil, faster than we can replenish them. And the side effects of our animal-protein-driven food economy include environmental toxins and the poisoning of the very air we all depend on for life.

These are serious problems; each of them deserves a book of their own. And they’re only the tip of the iceberg. If you want to learn more, I highly recommend J. Morris Hicks’s excellent work, Healthy Eating, Healthy World. For the purposes of this discussion, however, I want to focus on four problems that neither policy makers nor the media generally see as being connected to diet: two of the most significant environmental crises of our time, global warming and the depletion of America’s deep underground water resources; and the cruelty and violence done to two of the most vulnerable groups on the planet, animals and impoverished humans. We’ll see how reductionist thinking keeps us stuck, and how a wholistic approach can solve these multiple problems simultaneously.

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits