When I first switched to a plant-based diet, I continued to eat fish. I believed I was doing my body good. After all, I thought, fish are rich in omega-3 fatty acids, and omega-3 fatty acids are anti-inflammatory. Why wouldn’t I want this? What I didn’t realize was that fish have many unhealthy substances and that these harmful substances can negatively affect the body in numerous ways.

The fish example illustrates why we should never focus on just one nutrient in food while forgetting about the rest of the package. If our goal is to improve our overall health, we should remember the bigger picture. If we could be healthy by focusing only on isolated nutrients, we might adopt diets containing many Pop-Tarts because they’re a “good source” of B vitamins.

Of course, we all know it doesn’t work like that with Pop-Tarts, but do we hold fish to the same commonsensical standards? Let’s take a closer look.

The Good on Fish Consumption

As I mentioned, fish are an excellent source of omega-3 fatty acids—an essential fat with anti-inflammatory properties. Essential denotes a nutrient our bodies cannot produce and which must therefore come from dietary sources.[1] The so-called parent omega-3 fatty acid is alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), which is metabolically converted in humans to the long-chain omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Because the body converts ALA to EPA and DHA, only ALA is considered essential.

Still, EPA and DHA are important. They are what people commonly call good fats and are often used to justify eating fish. Fish get their EPA and DHA from eating algae, and many humans—although capable of converting ALA—get their EPA and DHA directly from eating fish. In other words, fish are the middlemen between the algae and the humans.

The Story of Vegans and Omega-3 Fatty Acid Intake

You may have heard that vegans are unable to convert enough ALA into EPA and DHA to meet the body’s needs and that they must, therefore, add fish to their diet or else take supplements. This is not necessarily true. As pointed out in a 2006 article published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition:[1]

Several case studies involving n−3-deficient patients [have] reported that intervention with ALA results in marked increases in plasma concentrations of both EPA and DHA. In addition, vegans who consume ALA but not EPA and DHA in their diets have low but stable concentrations of DHA in plasma. Together, these findings suggest that humans can convert meaningful quantities of ALA to EPA and DHA, particularly in the presence of a deficiency or a background of low n−6 fatty acids.

In other words, if you are a vegan eating a healthy diet with a low omega-6 fatty acid content, you will likely have a sufficient quantity of the long-chain omega-3 fatty acids available. Low omega-6 fatty acid content is the key. This effectively means that a diet must have not only limited animal foods but also limited junk foods (including vegan and vegetarian junk foods) for humans to effectively convert enough ALA to EPA and DHA. This statement represents a shift away from how many people think about omega-3 fatty acids: we must consider not only the total intake of omega-3 fatty acids but also the ratio of omega-6 fatty acids.

How does this work? High omega-6 fatty acid intake can result in up to a 40 percent lower conversion rate of ALA to EPA and DHA.[1] This is because both omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids use the same enzyme to convert their short-chain parent versions to their long-chain versions (i.e., ALA to EPA and DHA; LA [linoleic acid] to ARA [arachidonic acid]). The omega-6 fatty acids effectively win the battle for the use of this enzyme, limiting the body’s ability to convert ALA into EPA and DHA. Eating a diet with far less omega-6 fatty acids, such as a whole food, plant-based (WFPB) diet, prevents this from happening.

None of this is to say that fish are not a rich source of EPA or DHA. Whether fish are necessary or even preferable for that reason, however, is a different question.

Dietary Requirements for Omega-3 Fatty Acids

The Institute of Medicine sets the minimum dietary requirements for ALA at 1.1 and 1.6 grams per day for women and men respectively, 19–50 years old.[2] Additionally, 0.5–1 gram daily of EPA and DHA have been recommended for cardiovascular disease prevention and treatment (dietary ALA consumption has also shown cardioprotective effects). These protective effects were seen in potentially increasing amounts from 0.58–2.81 grams per day.

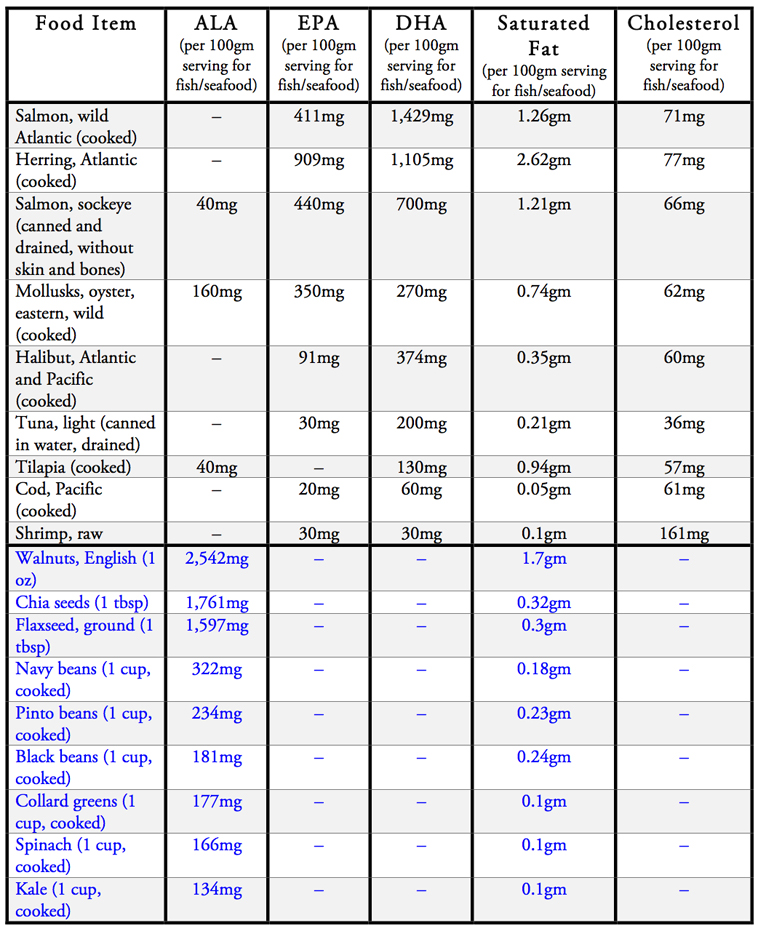

The table below summarizes the amounts of omega-3 fatty acids, saturated fats, and cholesterol in different foods.[3][4] A 100-gram serving of fish is equivalent to a 3.5-ounce portion.

The Bad on Fish Consumption

While fish may be a rich source of omega-3 fatty acids they are also packaged along with several other harmful substances to human health. The most harmful of these being saturated fat. Additionally, cholesterol, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dioxins, and mercury round out the other handful of harmful substances found in fish and seafood.

Saturated Fat and Cholesterol

Saturated fat has long been linked to cardiovascular disease. It is known to increase both LDL and total cholesterol levels.[5] Replacing just five percent of energy from saturated fat with the same amount of energy from polyunsaturated fatty acids (omega-3’s fall into this category), monounsaturated fatty acids, or carbohydrates from whole grains can reduce one’s risk of coronary heart disease by 25, 15, and 9 percent respectively.[6]

High saturated fat consumption also worsens blood pressure. Research has shown that it is possible to reduce blood pressure by decreasing saturated fat and increasing monounsaturated fat in the diet.[7]

Marine animals, like all animals, also have dietary cholesterol, whereas plant foods have no measurable amounts of cholesterol. Dietary cholesterol raises LDL cholesterol levels in the body to a smaller extent than saturated fats, but for every 200 milligrams of cholesterol consumed per 2,000 calories in the diet, LDL cholesterol rises on average between 8 to 10 mg/dl.[8]

Given that cardiovascular disease is the number one killer worldwide and that animal products are major contributors to the incidence and mortality of the disease, it would be prudent to avoid all animal foods, including those in the sea.

PCBs, Dioxin, and Mercury

PCBs, dioxin, mercury, and other toxic pollutants are also in the fish supply. These have a range of adverse effects, including neurological damage, liver and skin damage, and potentially decreased muscle tone and reflexes in infants.[9][10][11] Children are at the greatest risk for these effects because of their earlier development, but adults can also be harmed.

In 2004, the Food and Drug Administration and Environmental Protection Agency issued a joint advisory warning to pregnant and nursing mothers, women who may become pregnant, and young children about the toxic effects of mercury from fish consumption.[2] They recommend completely avoiding shark, swordfish, king mackerel, and tilefish and limiting consumption of a variety of other fish, including salmon, tuna, shrimp, pollock, and catfish, to 340 grams per week. This is equivalent to approximately 12 ounces of fish per week.

I don’t know about you, but alarm bells start going off for me when I hear official recommendations along these lines. In contrast, there is a reason official governmental or professional organizations never recommend indefinite limits on fruits, vegetables, beans, or whole grains. These are the foods that give us life and vibrancy.

Additional organic and inorganic compounds found in fish have also officially been labeled as carcinogenic to humans. These include PCBs, dioxins, toxaphene, dieldrin, and polybrominated diphenyl ethers.[11] The World Health Organization (WHO) provides a tolerable daily intake (TDI) of these substances to help us understand the levels that are potentially toxic to humans. However, given the rest of the package, the more cautious approach of avoiding these foods altogether seems more sensible.

Can we avoid these substances without avoiding fish? What if we choose farm-raised fish? Not so fast. A 2005 study analyzed the levels of carcinogenic compounds in farmed versus wild salmon. Investigators found the following:[11]

Many farmed Atlantic salmon contain dioxin concentrations that, when consumed at modest rates, pose elevated cancer and noncancer health risks. However, dioxin and DLCs are just one suite of many organic and inorganic contaminants and contaminant classes in the tissues of farmed salmon, and the cumulative health risk of exposure to these compounds via consumption of farmed salmon is likely even higher. As we have shown here, modest consumption of farmed salmon contaminated with DLCs raises human exposure levels above the lower end of the WHO TDI, and considerably above background intake levels for adults in the United States.

Both wild and farmed-raised fish contain carcinogens, but it appears that farm-raised fish are even more contaminated than their wild counterparts.

The Ugly on Fish Consumption

It’s one thing to point out individual harmful components of fish (or any other food substance), and another to evaluate disease, disability, and death rates corresponding to the consumption of these same food items. That’s what we will look at here.

Cardiovascular Disease and Fish Consumption

The belief that eating fish protects against heart disease is well-established in the US and other Western cultures. And if you were to look at the surface level, this is exactly what you would see—higher fish consumption may equal a decrease in heart disease. However, if you take a deeper look into the scientific literature, you’ll find that fish consumption itself may not be responsible for better heart health.

This was apparent when looking at fish consumption in different Mediterranean-style diets, as reported in a review article in the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. They concluded: “Dietary factors other than fish, such as the lower meat consumption associated to the higher fish intake, or other differences of lifestyle have perhaps intervened, helping to explain the healthy nature of the Mediterranean diet.”[12] (This also reflects the conclusions of a study that found provegetarian food patterns in the Mediterranean diet reduce mortality.[13]) Other studies have similarly found no significant reduction in heart disease risk from increased fish consumption.[14][15]

The Oxford Vegetarian Study compared vegans, vegetarians, and meat-eaters and their corresponding death rates due to ischemic heart disease.[16] Vegans and vegetarians had fewer heart disease deaths compared to their meat-eating counterparts. The study investigators also found no protective effects when they analyzed fish consumption specifically.

A look at fish consumption in the Iowa Women’s Health Study showed no protective effect on coronary heart disease or stroke mortality.[17] A study on Danish adults found no benefit with fish consumption and lower coronary heart disease rates in the general population but could not exclude a benefit for those at high risk for heart disease.[18] In another systematic review study in the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, analysis of fish consumption in 116,764 individuals showed mixed results:[19]

Fish consumption is not associated with reduced coronary heart disease mortality in low-risk populations. However, fish consumption at 40-60 g daily is associated with markedly reduced coronary heart disease mortality in high-risk populations.

To understand the different effects of fish consumption on high- versus low-risk populations, we must consider the starting point of each of those groups. People at high risk of heart disease are also typically individuals who eat a less healthy diet to begin with. Therefore, as we saw in the Mediterranean diet analysis previously, eating more fish could be a step in the right direction. But that does not mean fish itself is responsible for reducing heart disease. One has to look at the big picture in terms of overall dietary changes to see exactly what’s going on here.

Diabetes and Fish Consumption

Type 2 diabetes is another disease for which official dietary recommendations have encouraged eating fish. But fish consumption does not benefit and may even worsen diabetes.[20]

In 2011, a study in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition followed 36,328 women for an average follow-up period of 12.4 years.[21]Researchers found that as the women ate more fish the incidence of type 2 diabetes increased. The highest intake of fish consumption (at least 2 servings per day) was associated with the highest rate of type 2 diabetes.

Another review article published in 2014 looked at the prevalence of type 2 diabetes and meat consumption.[22] It found that as individuals went from vegan to vegetarian to pescovegetarian to meat-containing diets, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes increased. Vegans had a 2.9 percent prevalence of type 2 diabetes compared to 4.8 percent for pescovegetarians (individuals who eat fish but no other meat products).

One reason fish consumption might increase diabetes risk is the aforementioned fat content of marine life. Although many Americans believe that fish is a lean meat, naturally low in fat, numerous fish have fat content exceeding 20 percent of total calories.

Why is fat a problem? Because the root cause of type 2 diabetes is excess fat inside muscle cells. This causes insulin resistance to develop. So when you eat fatty fish, you get fatty muscle cells, which precede type 2 diabetes.

Summary and Final Conclusions

The consensus in our culture glorifies fish and seafood as health-promoting foods. They are not. Marine life is meant to stay where it comes from—in the water. It’s not preferable for human consumption if you’re concerned about your health.

When you hear about studies suggesting benefits from eating our finned friends, you are most likely hearing about individuals improving their health because they went from bad to less bad on the diet spectrum. Going from the standard American diet to any diet with fewer animal products and processed foods will do wonders for the body. Increasing fruit and vegetable consumption will help too. But we shouldn’t confuse less bad with good or assume that eating fish is the reason for broader health improvements.

Currently, no scientific evidence convincingly suggests that adding fish to an already healthy diet based on whole plant foods increases an individual’s health even more. If anything, the environmental toxins and nutrient content in fish and seafood make it more difficult for the body to ward off disease and illness.

I understand people’s thought processes and desire to improve their diet by eating fish. I, too, was a fish eater at one time. It was the last meat product I gave up on my journey to adopting a WFPB lifestyle. As I learned more about this class of meat though, I quickly realized that to achieve an optimal state of health, fish had to go. I’m happy to say that I’ve never looked back since ditching my fish habit. Should you decide to do the same, I’m certain you won’t look back either. Your body will be thanking you as well.

Five Fast Facts about Fish

- All fish contain cholesterol, with shrimp having higher cholesterol than other seafood.[3][4]

- PCBs, dioxin, mercury, and other toxic pollutants are concentrated in the fish supply.[9][10][11]

- Numerous studies investigating fish consumption have yielded mixed results; the Iowa Women’s Health Study, for example, showed no protective effect for coronary heart disease or stroke mortality.[17]

- The FDA and EPA issued a joint advisory warning to pregnant and nursing mothers about the toxic effects of mercury from fish consumption.[2]

- There is no scientific evidence showing the addition of fish to a healthy diet increases an individual’s health even more.

References

- Arterburn LM, Hall EB, Oken H. Distribution, interconversion, and dose response of n-3 fatty acids in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(6 Suppl):1467S-1476S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1467S

- Gebauer SK, Psota TL, Harris WS, Kris-Etherton PM. n-3 fatty acid dietary recommendations and food sources to achieve essentiality and cardiovascular benefits. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(6 Suppl):1526S-1535S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1526S

- United States Department of Agriculture. National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release 21.

- United States Department of Agriculture. National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release 28.

- Siri-Tarino PW, Sun Q, Hu FB, Krauss RM. Saturated fatty acids and risk of coronary heart disease: modulation by replacement nutrients. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2010;12(6):384-390. doi:10.1007/s11883-010-0131-6

- Li Y, Hruby A, Bernstein AM, et al. Saturated Fats Compared With Unsaturated Fats and Sources of Carbohydrates in Relation to Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(14):1538-1548. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.055

- Rasmussen BM, Vessby B, Uusitupa M, et al. Effects of dietary saturated, monounsaturated, and n-3 fatty acids on blood pressure in healthy subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(2):221-226. doi:10.1093/ajcn/83.2.221

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Diet and Health; Woteki CE, Thomas PR, editors. Eat for Life: The Food and Nutrition Board’s Guide to Reducing Your Risk of Chronic Disease. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1992. Chapter 6, Fats, Cholesterol, And Chronic Diseases. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK235018/.

- Longnecker MP, Rogan WJ, Lucier G. The human health effects of DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) and PCBS (polychlorinated biphenyls) and an overview of organochlorines in public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1997;18:211-244. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.211

- Liu J, Lewis G. Environmental toxicity and poor cognitive outcomes in children and adults. J Environ Health. 2014;76(6):130-138.

- Foran JA, Carpenter DO, Hamilton MC, Knuth BA, Schwager SJ. Risk-based consumption advice for farmed Atlantic and wild Pacific salmon contaminated with dioxins and dioxin-like compounds. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(5):552-556. doi:10.1289/ehp.7626

- García-Closas R, Serra-Majem L, Segura R. Fish consumption, omega-3 fatty acids and the Mediterranean diet. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1993;47 Suppl 1:S85-S90.

- Martínez-González MA, Sánchez-Tainta A, Corella D, et al. A provegetarian food pattern and reduction in total mortality in the Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea (PREDIMED) study [published correction appears in Am J Clin Nutr. 2014 Dec;100(6):1605]. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100 Suppl 1:320S-8S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.071431

- Ascherio A, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci EL, Willett WC. Dietary intake of marine n-3 fatty acids, fish intake, and the risk of coronary disease among men. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(15):977-982. doi:10.1056/NEJM199504133321501

- Folsom AR, Demissie Z. Fish intake, marine omega-3 fatty acids, and mortality in a cohort of postmenopausal women. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(10):1005-1010. doi:10.1093/aje/kwh307

- Appleby PN, Thorogood M, Mann JI, Key TJ. The Oxford Vegetarian Study: an overview. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70(3 Suppl):525S-531S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/70.3.525s

- Folsom AR, Demissie Z. Fish intake, marine omega-3 fatty acids, and mortality in a cohort of postmenopausal women. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(10):1005-1010. doi:10.1093/aje/kwh3071

- Osler M, Andreasen AH, Hoidrup S. No inverse association between fish consumption and risk of death from all-causes, and incidence of coronary heart disease in middle-aged, Danish adults. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(3):274-279. doi:10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00600-5

- Marckmann P, Grønbaek M. Fish consumption and coronary heart disease mortality. A systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1999;53(8):585-590. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600832

- Kaushik M, Mozaffarian D, Spiegelman D, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, fish intake, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(3):613-620. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.27424

- Djoussé L, Gaziano JM, Buring JE, Lee IM. Dietary omega-3 fatty acids and fish consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93(1):143-150. doi:10.3945/ajcn.110.005603

- Barnard N, Levin S, Trapp C. Meat consumption as a risk factor for type 2 diabetes [published correction appears in Nutrients. 2014;6(10):4317-9] [published correction appears in Nutrients. 2014;6(3):1181]. Nutrients. 2014;6(2):897-910. Published 2014 Feb 21. doi:10.3390/nu6020897

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits