Our children are growing up in a world very different from what many adults remember from their youth. Regarding food and nutrition, these profound differences have a major impact on personal and planetary health. It is important to recognize the implications of these changes from a public health, environmental, and educational perspective.

One hundred years ago most people were more directly involved in their food, whether through growing, cooking, or learning about it. People ate more local seasonal foods, and the processed food industry was in its infancy. Today the average grocery store has up to fifty thousand items, most of them processed to have a long shelf life but containing fewer nutrients and more chemicals than whole foods contain.[1] We consume items concocted in chemistry labs rather than those grown in nature, nourished by sunshine, soil, water, and air. By messing with nature, we also provoke climate change and other ecological disturbances. Humans (except farmers) are the only species able to survive without spending a significant amount of their day in the quest for food. And when our farming practices do not respect the natural world, consequences always follow.

Our former connection to food was instinctual: we needed to learn how to cultivate, prepare, and store food to ensure survival. We have lost that precious connection. With the widespread availability of inexpensive processed foods, we are eating fewer whole foods, a trend directly affecting our health. In many homes, meals made from scratch are only prepared for special occasions, and children aren’t learning about nutrition or food preparation.

The knowledge, technical skills, and social norms that preserve food literacy have been lost. Schools are increasingly addressing societal problems that are not being taught in the home, such as sexual abuse and bullying, but are eliminating home economics, which has needed a nutritional makeover to reflect contemporary knowledge about nutrition and health and to honor the early founders of home economics such as Ellen Richards who transformed our home environment by applying scientific principles to air, water, and food. In short, the large body of evidence about foods that promote health is not being taught in most schools.

This must change if children are to appreciate how nutrients, starting with nutrients in the soil, are vital for their development. Sadly, most schools do not include food literacy in their curricular agenda. Never before in our history have children been expected to have a lower lifespan than that of their parents due primarily to a poor diet; this can and should be prevented through positive hands-on educational strategies.

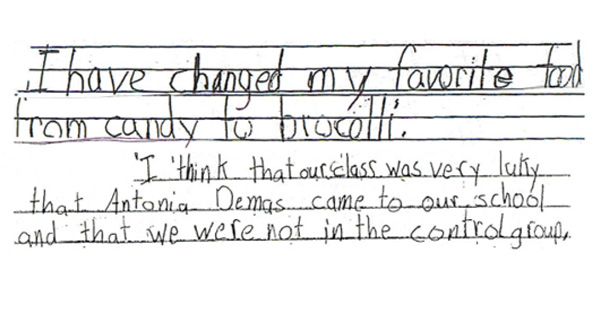

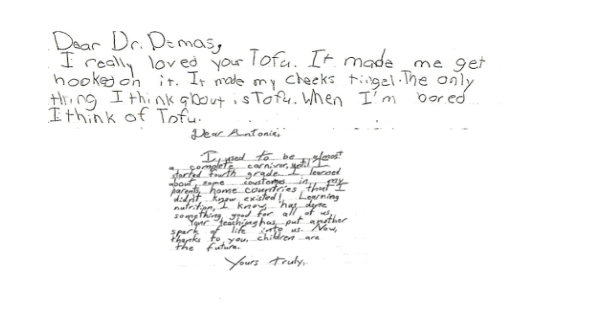

Children are naturally curious. Through their sensory exploration—seeing, tasting, touching, smelling, and hearing—they first learn about the world. Early childhood is the ideal time to help them engage these senses and create positive experiences with health-promoting foods. This does more than expand the palate; by exposing children to a wide variety of foods, flavors, and food traditions, we can foster acceptance of not only healthy foods but also the diverse people and plants of the world.

Wholesome food connects us to nature on a fundamental level, and this connection with the natural world is vital to sustaining our future and that of the planet. We must educate young children about healthy eating to ensure they develop the intellectual and practical skills necessary to prevent costly diet-related diseases; through this process, we can also expose them to the joy and wonder of growing and cooking healthy food. Food literacy education done in a positive, nonjudgmental, sensory way can address these concerns and reverse the alarming projections for the future. Our children deserve access to food literacy education to prevent them from acquiring diet-related diseases and to protect our precious home—the earth.

This article was originally published in Perspectives Essay Series for World Food Day (October 16, 2013). It has been edited for consistency with CNS editorial guidelines.

References

- Consumer Reports. What to do when there are too many product choices on the store shelves? January 2014. https://www.consumerreports.org/cro/magazine/2014/03/too-many-product-choices-in-supermarkets/index.htm

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits