Numerous authoritative public health agencies have reiterated the plant-based diet’s ability to provide more-than-adequate protein levels, including the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND).[1] In a 2016 position statement on vegetarian diets, AND authors cite several research studies from previous decades, reaching the following stance:

Vegetarian, including vegan, diets typically meet or exceed recommended protein intakes, when caloric intakes are adequate. The terms complete and incomplete are misleading in relation to plant protein. Protein from a variety of plant foods, eaten during the course of the day, supplies enough of all indispensable (essential) amino acids when caloric requirements are met [. . . ] Protein needs at all ages, including for athletes, are well achieved.

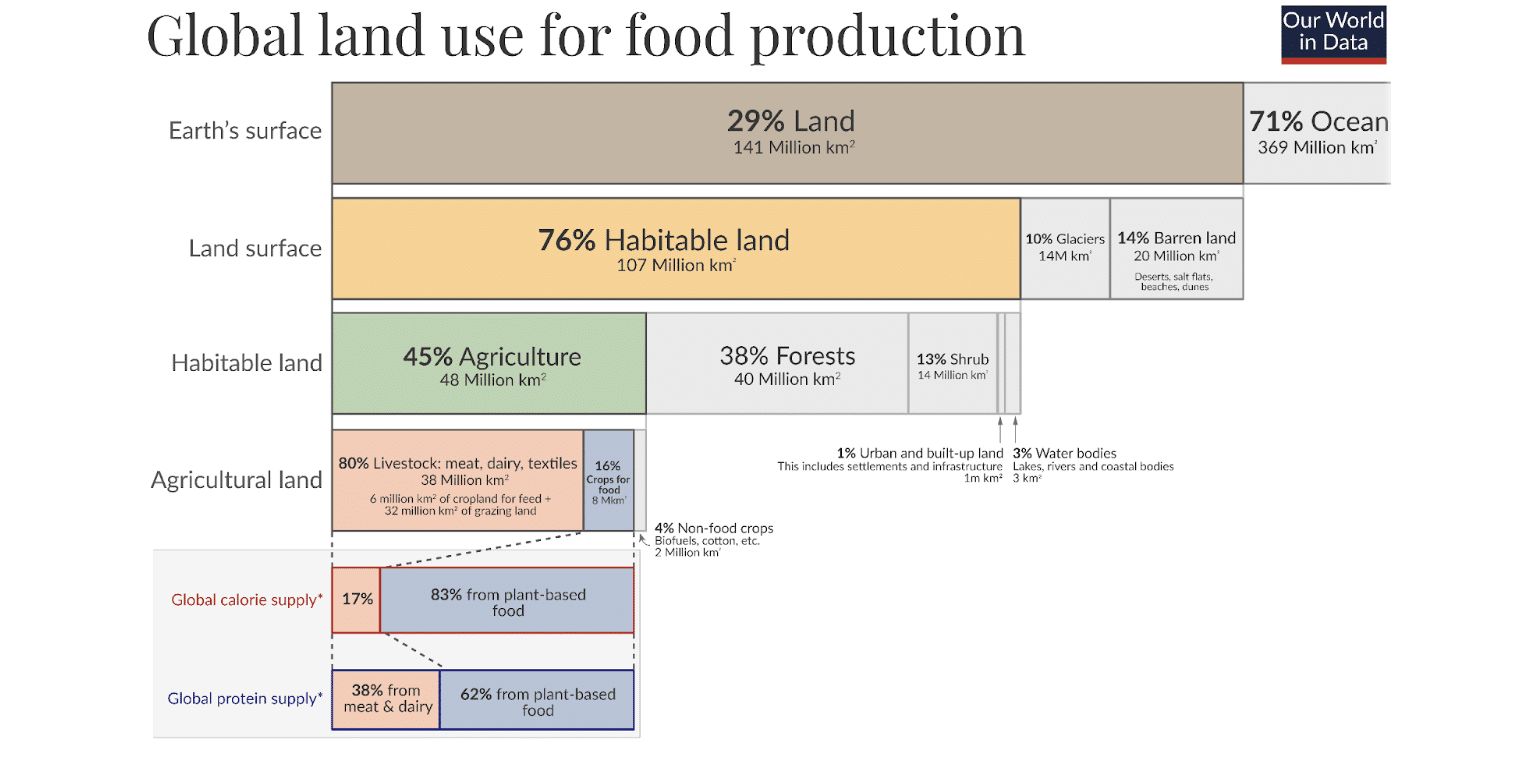

In other words, animal foods are not necessary for protein. Most of the world’s protein already comes from plants anyway—about 62 percent of the world’s protein comes from plant-based foods, despite those crops only accounting for 16 percent of agricultural land use.[2]

Data from UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and Roser M. and Poore and Nemecek; Prepared by Ritchie H[2] CC-BY

And Yet! Measures of Protein Quality

Although the AND position paper quoted above refutes the long-held belief that animal-based proteins are more complete than plant proteins, this misconception persists. Where did it originate? How have different proteins been measured historically, and are these measures useful when assessing the healthfulness of foods today?

Throughout the past century, researchers have used several methods for measuring the value of different proteins, including protein efficiency ratio (PER), biological value (BV), amino acid score (AAS), and protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score (PDCAAS). Each of these measures has been preferred by nutrition researchers at different times. Though there are differences, they have all been used (intentionally or otherwise) to reinforce the supposed value of animal-based foods.[3]

A food’s PER is calculated by dividing the gain in body mass by protein intake. In effect, it measures a protein’s ability to promote body growth. BV determines how efficiently the body uses various proteins by measuring the proportion of nitrogen retained in the body. The more recent measures, AAS and PDCAAS, essentially measure how readily the body can use the amino acids present in different proteins. Because animal-based proteins are more similar to ours than plant-based proteins, they are more efficiently used by our bodies, thus giving rise to the idea that they are of a higher quality.

But all of these measures of protein quality rest on the same assumption: they assume that the highest quality proteins are those that most efficiently promote growth in the body.

Does faster growth equal better health outcomes? Not according to a large body of evidence. Foods containing “high-quality” animal protein are associated with increased serum cholesterol levels, heart disease mortality, the incidence of various cancers, and several other chronic diseases.[3] Decades of laboratory research have demonstrated numerous biological mechanisms by which “high-quality” animal protein could imperil health. Foods containing “high-quality” animal protein are pro-inflammatory: a single high-fat, animal-based meal triggers rapid inflammation in the body and damages arterial function.[4] While they arguably do not go far enough in their assessment, the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has labeled processed meat as carcinogenic to humans and red meat as “probably carcinogenic.”[5]

To return to the AND position statement quoted above, individuals who reduce or remove animal protein from their diet have a decreased “risk of certain health conditions, including ischemic heart disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, certain types of cancer, and obesity.”[1] In fact, other research has shown that these conditions can be reversed. And the longest-lived people in the world eat predominantly plant-based diets.[6]

Here’s what I find strange: the measures of protein value mentioned above—PER, BV, AAS, PDCAAS—entirely neglect this context. Yet they are repeatedly cited as reasons to continue eating animal-based foods. Why?

References

- Melina V, Craig W, Levin S. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(12):1970-1980. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2016.09.025

- Ritchie H, Roser M. Half of the world’s habitable land is used for agriculture. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. February 16, 2024. Accessed January 7, 2025. https://ourworldindata.org/global-land-for-agriculture

- Campbell TC. The future of nutrition: an insider’s look at the science, why we keep getting it wrong, and how to start getting it right (2020). BenBella Books, Inc.

- Vogel RA, Corretti MC, Plotnick GD. Effect of a single high-fat meal on endothelial function in healthy subjects. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79(3):350-354. doi:10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00760-6

- International Agency for Cancer Research. Press release: IARC monographs evaluate consumption of red meat and processed meat. (2015).

- Buettner D, Skemp S. Blue Zones: Lessons From the World’s Longest Lived. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2016;10(5):318-321. Published 2016 Jul 7. doi:10.1177/1559827616637066

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits