Life expectancy as an indicator of health is limited. It’s possible to live longer without necessarily living better or more healthily, and no one wants to spend their final years—or decades—suffering from disabling or painful diseases. That’s why a more useful statistic is health-adjusted life expectancy (HALE), which accounts for years lived in less than full health.[1]

Nevertheless, changes in life expectancy can help us assess our collective health history. And there are a few lessons we can glean from the long-term trends.

Centuries of Progress . . . Why?

Life expectancy has lengthened considerably throughout most wealthy countries since at least before the mid-19th century. Beginning in 1840, life expectancy at birth increased by about three months per year.[2] But most of that increase was due to reduced infant and childhood mortality. It wasn’t until almost 1960 that increases in life expectancy slowed down and: “depended on increasing survival among the older adult population”. In the US, for example, “the probability of a 65-year-old surviving to age 85 doubled between 1970 and 2005.”

So, life expectancy gains in the 19th century were due to a reduction in childhood infectious diseases; even most deaths at the turn of the 20th century were the result of infection, so reducing the dangers of infection increased our chances of survival. Conversely, “when chronic diseases dominate deaths,” as they have in recent decades, “people often live with diagnosed disease and with treatment for long periods of time.”

This is something our medical system has excelled at—managing chronic diseases so that we live longer. (Not necessarily reducing the incidence or reversing the disease conditions, but prolonging survival.) Cardiovascular disease (CVD) provides probably the most obvious example: for over five decades, the chances of surviving a heart attack have consistently increased. Indeed, our medical system’s ability to reduce mortality rates from CVD accounts for about 60% of the increase in life expectancy from 1970 to 2000!

Here are a few statistics that illustrate these trends (see charts below for sources):

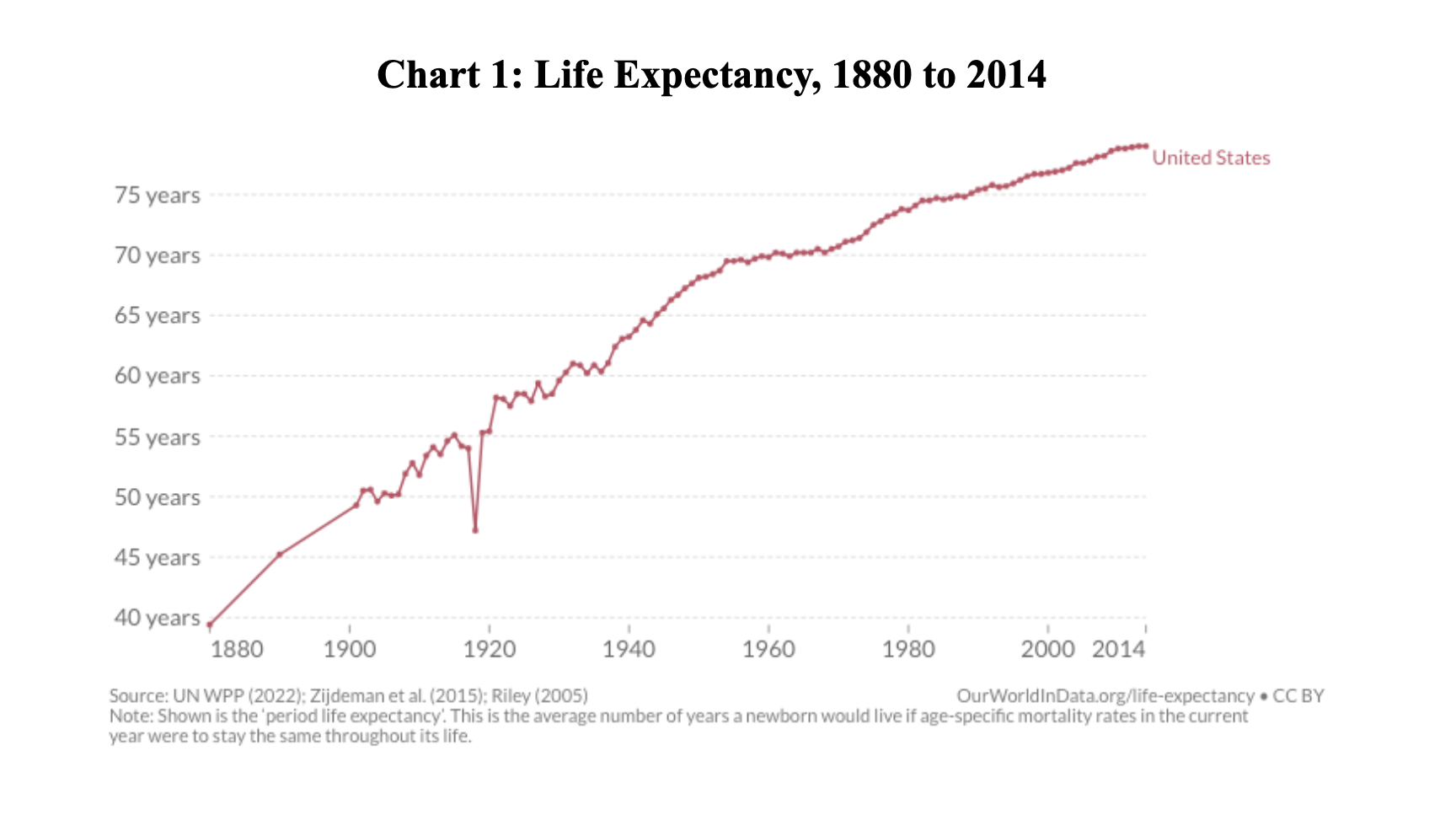

- From 1880 to 2014, life expectancy in the US more than doubled, increasing from 39.4 years to 79 years (Chart 1).

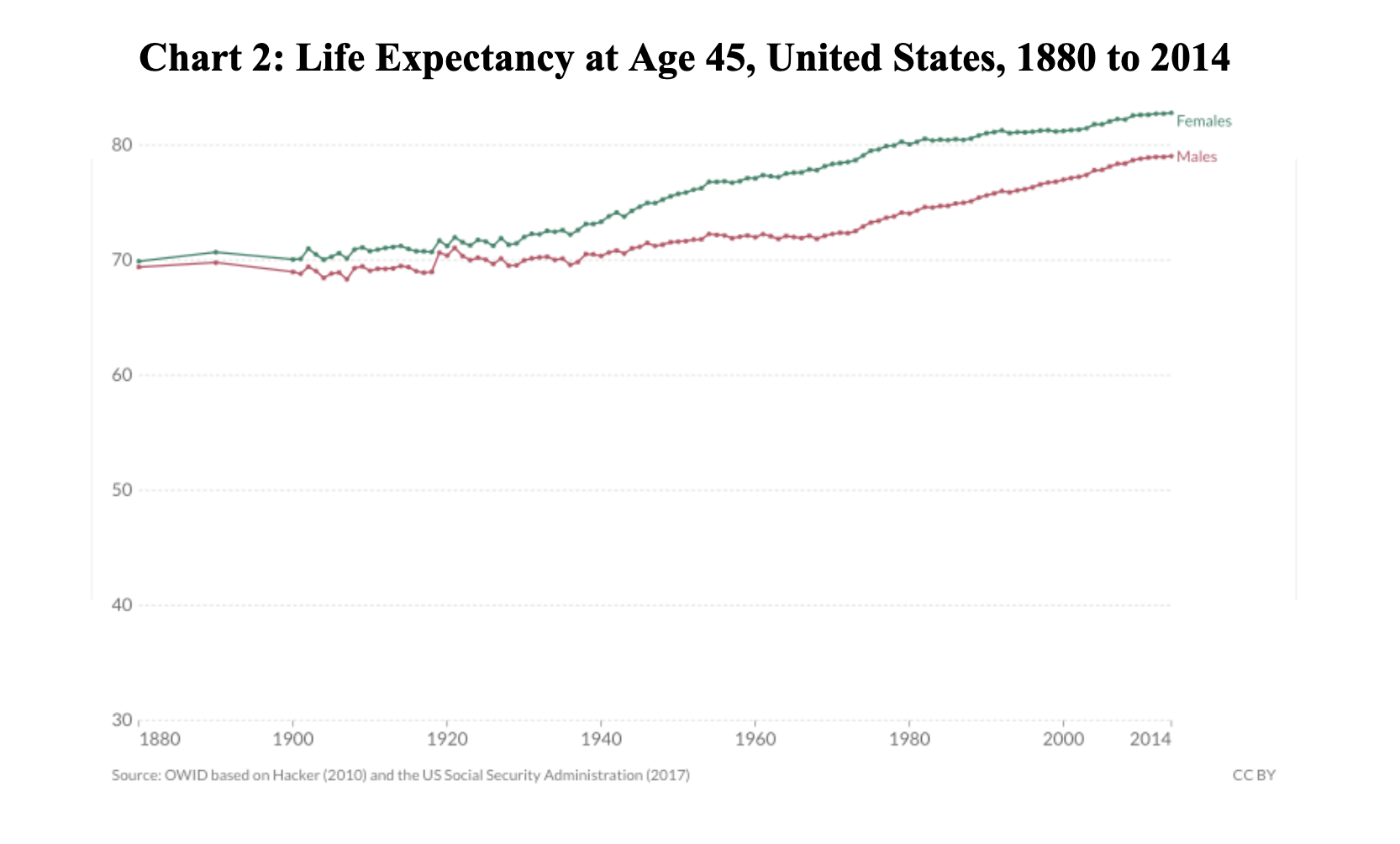

- In the same 134-year period, life expectancy for a 45-year-old female in the US increased by less than 13 years; for a 45-year-old male in the US, the increase was less than ten years (Chart 2). In other words, life expectancy improvements have been skewed by reduced mortality rates among the younger population.

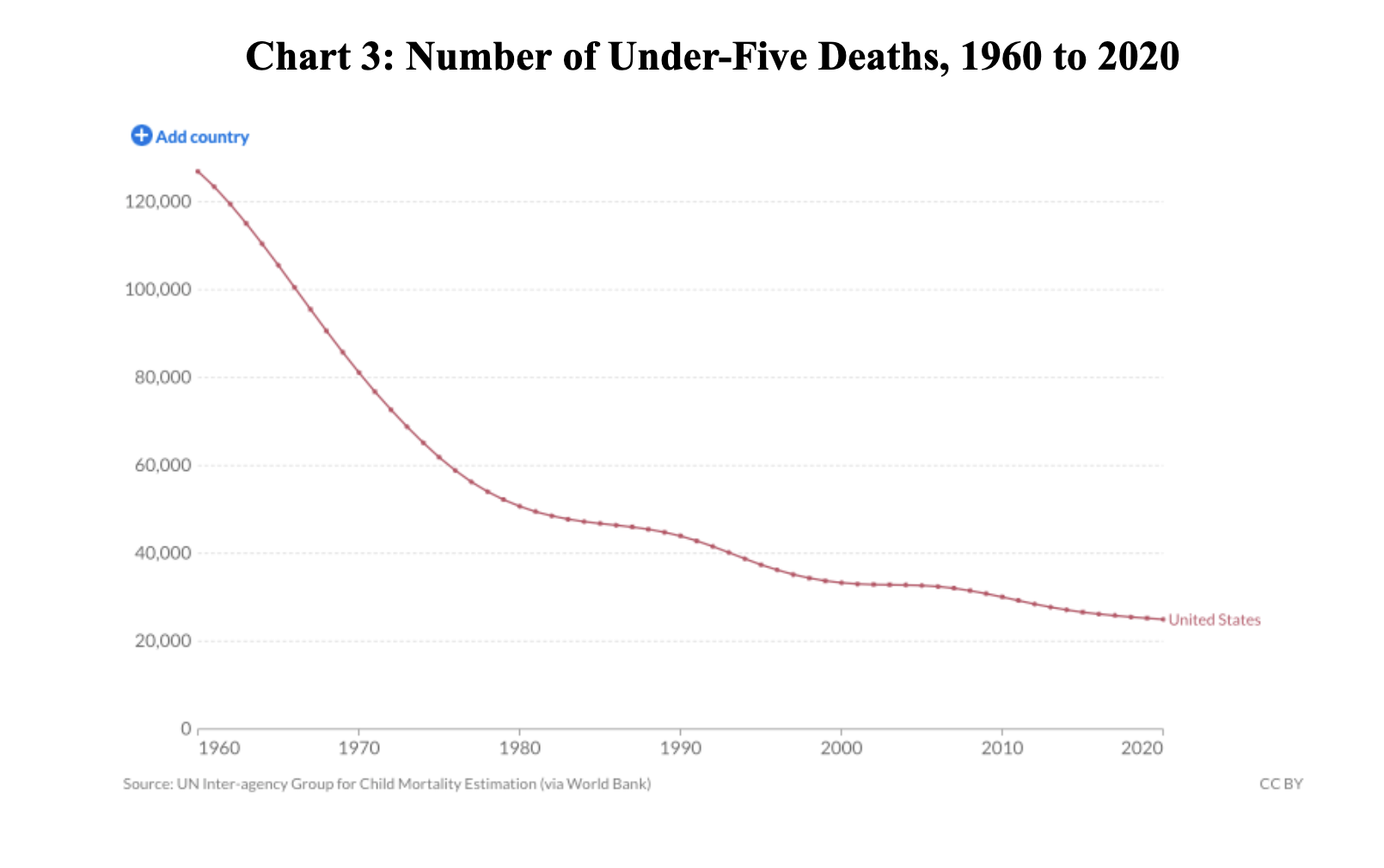

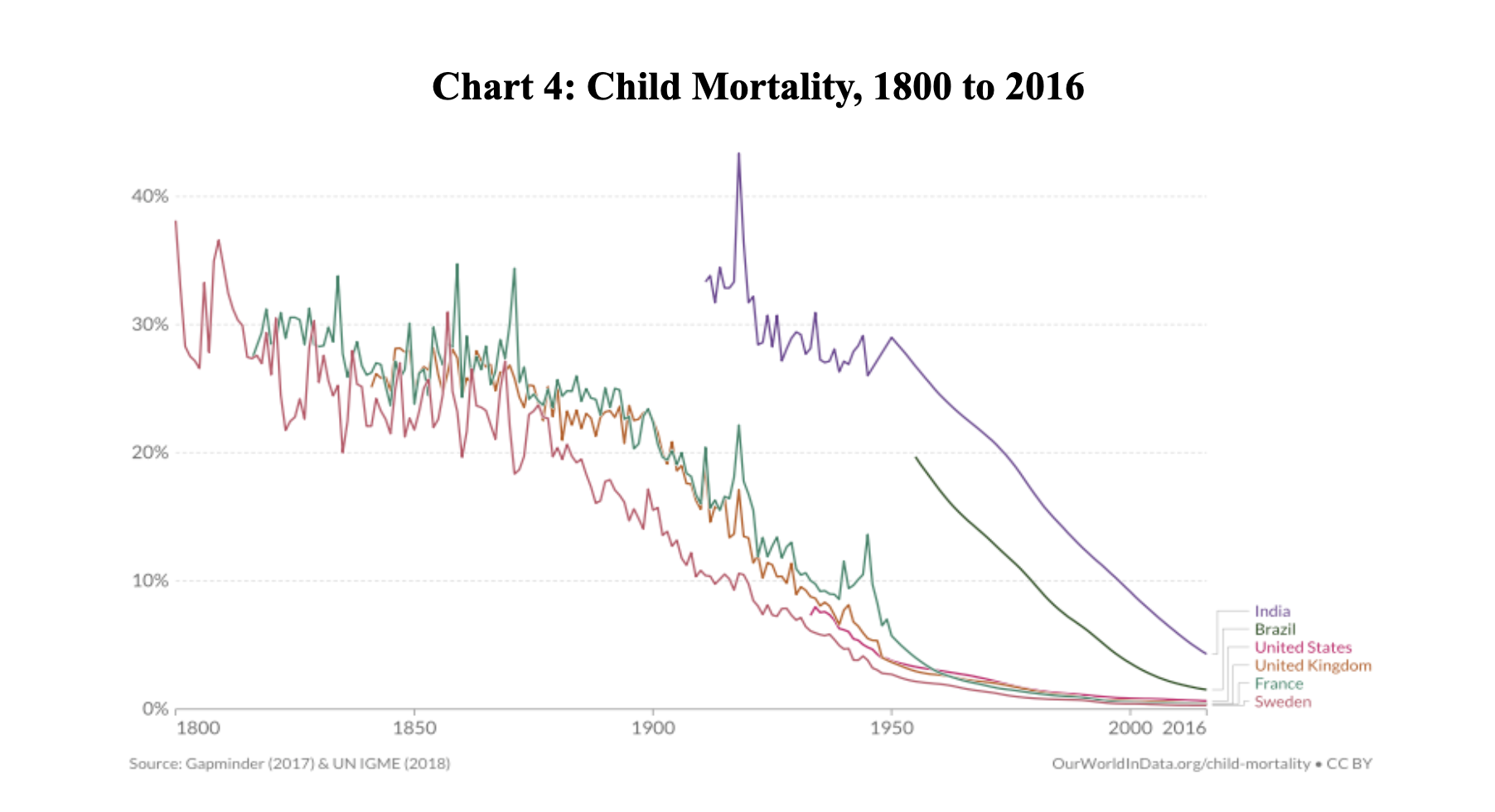

- A reduction in childhood mortality still contributes to life expectancy gains. The number of under-five deaths in the US has decreased by 80% since 1960 (Chart 3). However, we reduced child mortality much more in the previous century: in the mid-19th century, it was common for more than a quarter of all children to die before the age of five, compared to only three percent in the US in 1960 (Chart 4).

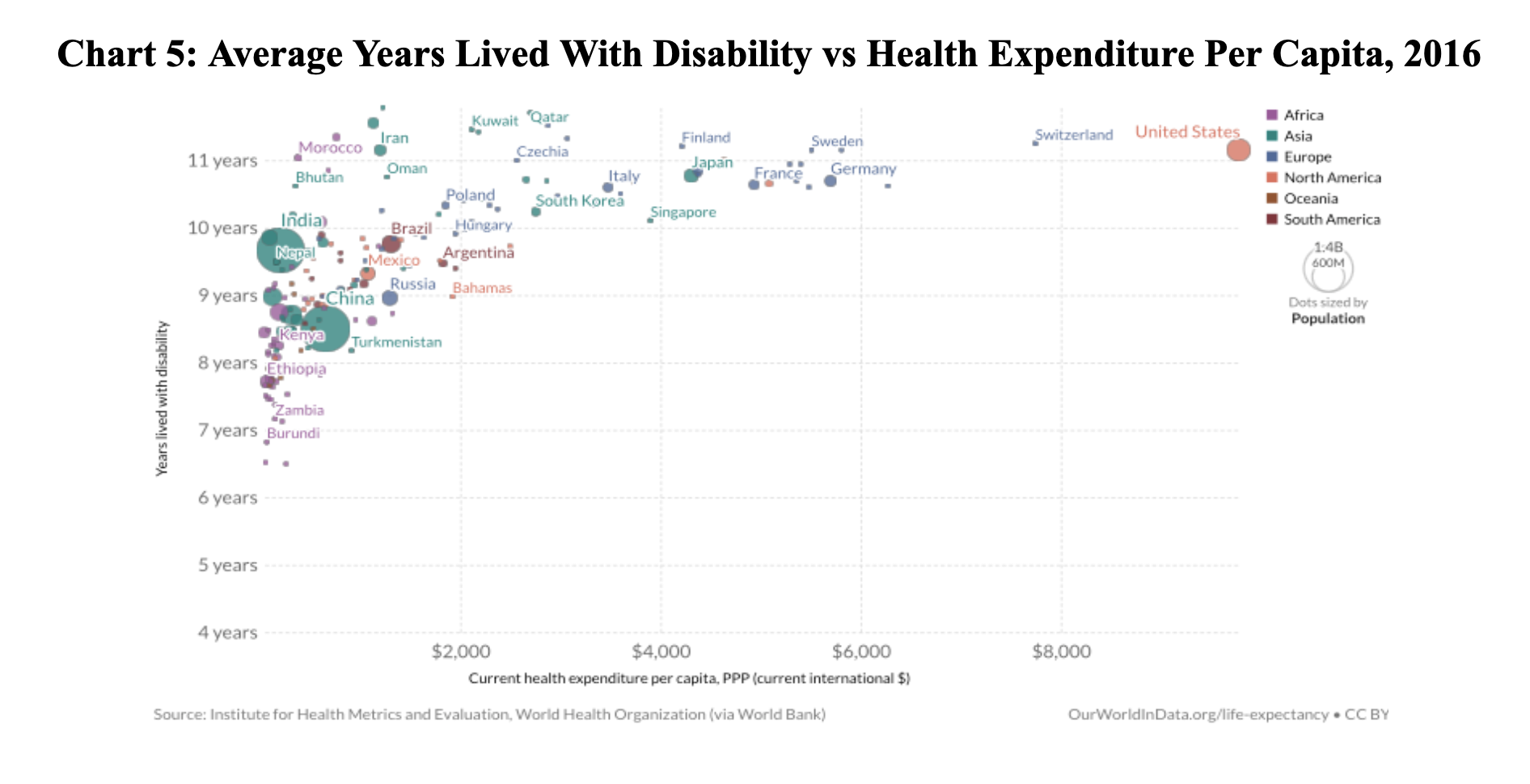

- The US has done relatively well surviving with disease, but our health expenditure per capita far outpaces the rest of the world (Chart 5).

This final point demonstrates why the compression of morbidity hypothesis is so appealing. This is a decades-old public health idea developed by Stanford professor of medicine James Fries that suggests the burden of lifetime illness might be compressed into a shorter period before death.[3] Unfortunately, researchers since have empirically demonstrated the opposite.[2] They conclude: “When morbidity is defined as major disease and mobility functioning loss [. . .] compression of morbidity may be as illusory as immortality.”

More Recent Trends

So, there may be valid concerns about the compression of morbidity theory, but overall, we’ve enjoyed significant gains in the past two centuries. What about more recently?

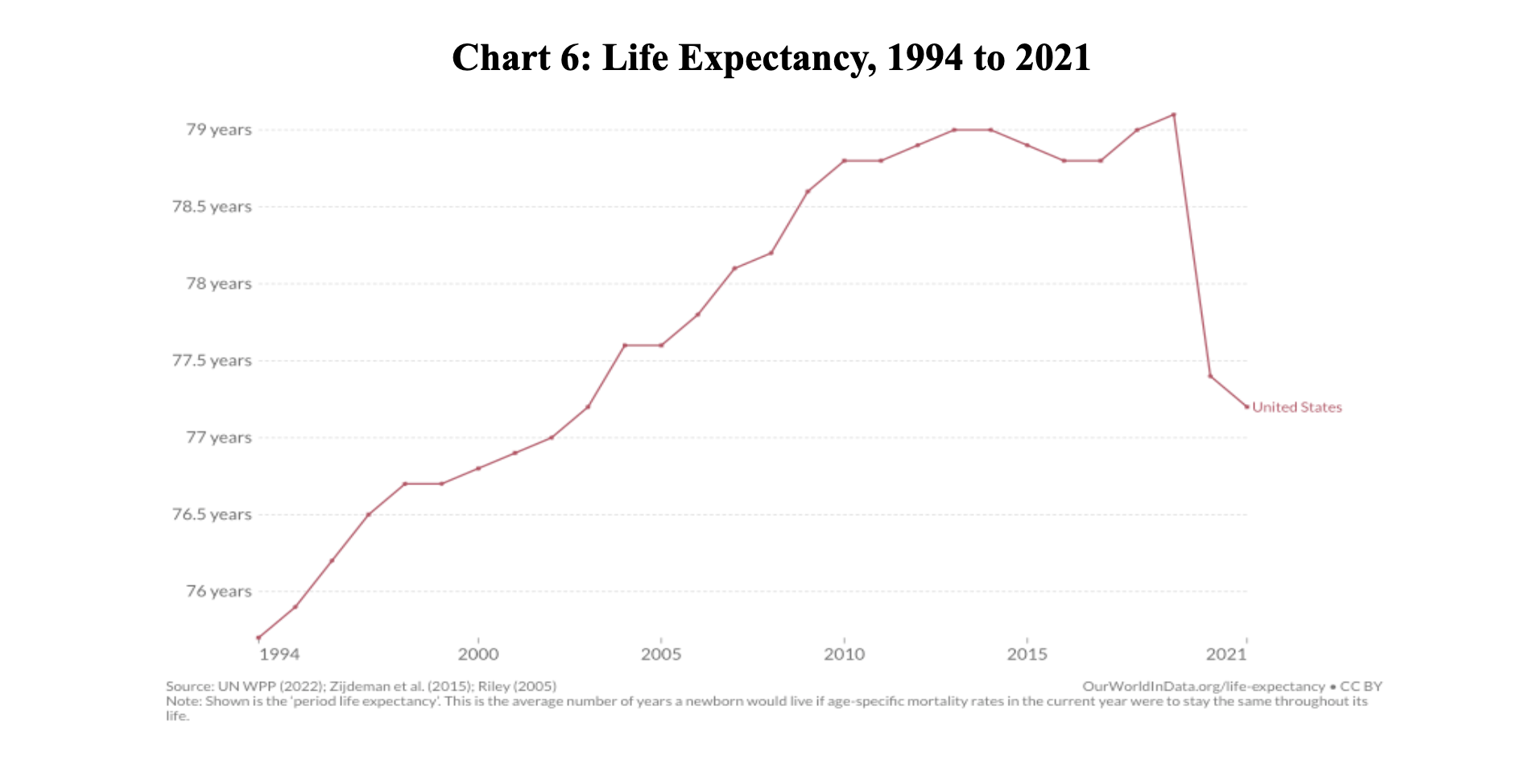

The COVID pandemic—and this won’t come as a surprise to anyone—severely affected life expectancy. What might surprise you is that even before the pandemic, life expectancy in the US was already struggling. From 2013 to 2017, life expectancy decreased (Chart 6), lagging behind most other high-income countries. And this gap widened during the pandemic,[4][5] which researchers have attributed to the coinciding opioid epidemic and increasing “deaths of despair”—overdoses, suicides, alcoholic liver disease, etc.

This backslide can also be linked, at least in part, to preventable lifestyle-related diseases, which might contribute to profound physical, psychological, and economic distress.

To answer the question posed by the title of this article, then: there are numerous reasons we are living shorter lives. This suggests a multi-pronged approach might be the best way to get back on track and continue to extend life expectancy.

Solutions

A 2021 article published in Annual Review of Public Health criticized the “deaths of despair” narrative and suggests a more targeted focus on the primary drivers of the life expectancy decline, including:

- policies that reduce drug overdoses;

- understanding and mitigating the causes of slowing heart disease mortality rates; and

- decreasing access to the means of completing suicides and homicides, including changing firearm laws.[6]

As they conclude: “Big-picture narratives are often compelling because of their simplicity and ability to explain it all, but they risk missing the trees for the forest.” If nutrition can play a role in pruning some of those trees, it can help reverse the troubling trends of recent years. Although, “substantial strides have been made in dealing with the consequences of disease,” we still have a long way to go to prevent, delay, or eliminate chronic diseases. The incidence of a first heart attack didn’t change very much from the 1960s to the 1990s, even though we greatly improved our ability to respond to that crisis.[2] The next step is to prevent it altogether. And that’s where nutrition can play a profound role.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Healthy life expectancy (HALE) at birth. Accessed December 28, 2022. https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/66.

- Crimmins, E. M. & Beltran-Sanchez, H. Mortality and morbidity trends: is there compression of morbidity? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 66, 75–86, doi:10.1093/geronb/gbq088 (2011).

- Fries, James F. (1980). “Aging, Natural Death, and the Compression of Morbidity” (PDF). New England Journal of Medicine. 303 (3): 130–5. doi:10.1056/NEJM198007173030304. PMC 2567746. PMID 7383070. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-11. Retrieved 2011-03-31.

- Lewis, T. Why life expectancy keeps dropping in the u.s. as other countries bounce back. Scientific American. November 21, 2022. Accessed December 28, 2022. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-life-expectancy-keeps-dropping-in-the-u-s-as-other-countries-bounce-back1/.

- Rakshit S, McGough M, Amin K, and Cox C. How does u.s. life expectancy compare to other countries? Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker. December 6, 2022. Accesssed December 28, 2022.https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/u-s-life-expectancy-compare-countries/#Life%20expectancy%20at%20birth%20in%20years,%201980-2021

- Harper S, Riddell CA, King, NB. Declining life expectancy in the united states: missing the trees for the forest. Annual Review of Public Health 42, 381–403 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-082619-104231

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits