The following is an article from a Community Grant recipient.

AmaruArts is an intercultural team based in Ecuador that promotes revitalization of the biodiversity and health of the lands and peoples of the Tropical Andes. This region is among the world’s centers of origin of cultivated plants and is the most diverse of all global biodiversity hotspots. This is due not only to tropical location and topographic variation, but also to the sophisticated agricultural civilizations that coevolved here for millennia. Despite being decimated by European conquest and five centuries of colonization, these Indigenous peoples, and remnants of their vast variety of crops and associated knowledge, survive. But they are being lost now as a result of global policies and technologies that disregard the sacredness of life on our planet.

AmaruArts seeks to preserve this endangered cultural wisdom, which we believe holds many keys for our world gone astray.

I was raised in Quito, in a household where poetry, music, and theatre were commonplace; later, my brother and I formed an Andean music band with some high school friends. This appreciation for and cultivation of the arts was important in shaping my identity and eventually my work. For my graduation project, I studied the impacts of missionary activities on the culture of Indigenous communities in Imbabura—another very informative experience. Living with traditional Kichwa families in both the Andes and the Amazon, I was immersed in their cultures and became conversant in their language. With that, I came to understand and appreciate their worldviews, which consider humans interconnected with nature in a way that has been lost to most “modern” societies.

According to the Kichwa philosophy of life, Earth and the universe are conscious and alive; the Sun and the Moon, mountains, soil, water, plants, and animals are all living beings, akin to extended family; and principles of respect, gratitude, and ayni (reciprocity) apply to all forms of life. I was fascinated by their holistic vision of time and space, present in oral histories, in daily life, and in community ceremonies and festivities.

When I returned to Quito, it became brutally apparent to me that our society is divorced from the natural world and the Indigenous peoples of our country, and that we are oblivious to the rapid destruction of both. Until the 1990s, Indigenous languages (such as Kichwa) were not taught or even permitted in schools, and while children may have had some exposure to the language from elders at home, they did not learn to speak their own language. These losses have been compounded by the migration of youth away from rural communities for work, which has been an ongoing struggle for a long time.

Since the 1970s, change has accelerated even more as a result of the “Green Revolution” and the oil boom. The introduction of hybrid seeds dependent on chemical fertilizers and pesticides increased soil erosion and loss of native seed varieties while harming the health of farmers, consumers, and entire ecosystems. Meanwhile, the adoption of processed foods into the diet has corresponded with huge surges in degenerative diseases that were previously rare. Even in rural areas, pharmaceutical drugs and clinics have displaced most of the Jambik wasi (medicine houses) where skilled healers use plants and natural treatments.

Seeing and experiencing all of these challenges firsthand has had a profound effect on me. It awoke in me the need to teach youth to value and learn the cultural knowledge and wisdom of their elders.

After studying anthropology and languages at universities in Quito, I sought more practical solutions to the problems I was seeing in traditional communities. My research led me to explore the potential of cinema and multimedia as tools to support Indigenous cultural survival, and I ended up in the best social communication and cinema program in Latin America, at the University of Sao Paulo (USP) in Brazil. After graduating, I returned to Ecuador where I was contracted to produce an educational video for a local NGO (CEIMME). Through that opportunity, I met Jeff, a US American who was—at the behest of leaders of the Kichwa Indigenous federation ECUARUNARI-Pichincha (PRR)—seeking a videographer to film the Fiesta del Coraza in San Rafael and Inti Raymi in Cayambe.

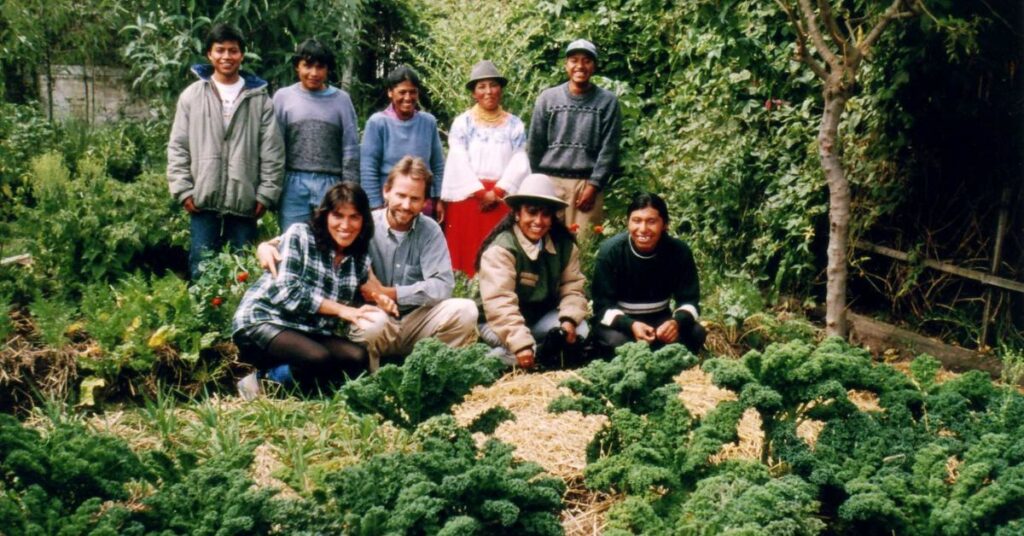

Jeff was working with PRR as the technical coordinator of the Permacultura Cayambe (PC) project to help address problems of land degradation and outmigration from their communities. In practice, they focused on four main components: 1) a nursery and training center; 2) a community school; 3) an ecotourism project that helped support the school; and 4) courses, workshops, and resident apprenticeships for local youth and visiting students. The school was built in the region’s most marginalized community by working in mingas (a Kichwa word that describes collaborative community work).

In a culmination of two month’s preparation connected with activities of the PC project, the All Species Project (ASP) prepared a musical play as part of the Inti Raymi festivities to celebrate the agricultural wisdom of their ancestors. Contrary to the stereotype of being “backward,” the Cayambi-Caranquis were master horticulturists, landscape architects, and watershed managers. They combined headwater forests, greenbelts, terraces, swales, canals, and reservoirs for soil and water conservation, irrigation, and microclimate management. Their camellones (alternating raised beds and canals that produce favorable environmental effects by reducing moisture and temperature extremes) in the humid valleys represent the world’s most sustainable agricultural system and were far more productive than the “modern” monocultures (cattle, flowers) that occupy the land today.

But the most captivating part of the project, for me, was the PC center located in the outskirts of Cayambe. Here, a tiny barren lot (0.12 acre) was transformed into a food forest, project headquarters, and demonstration site. Components of the design included rooftop rainwater storage tanks, a greenhouse, a multistory garden and tree nursery, an herb spiral, miniature aquaculture ponds, a solar guinea pig pen, compost and earthworm systems, and a seed bank. Heirloom seeds were collected and exchanged, and over 70 native tree and shrub species were distributed in participating communities.

AmaruArts is developing four full-day workshops for children and their mothers in rural Andean communities, in which participants will learn from local leaders about agriculture, health, and nutrition.

I immediately felt at home here, in what was a family environment. The woman who came on weekdays to prepare lunch had a wide repertoire of native dishes and medicinal plant remedies. Lunch was shared communally, with extra food always prepared for unexpected guests. Community visitors often came with their children, as did local elders who freely shared their stories. On weekends and evenings, the space became a gathering place for youth to socialize and play music.

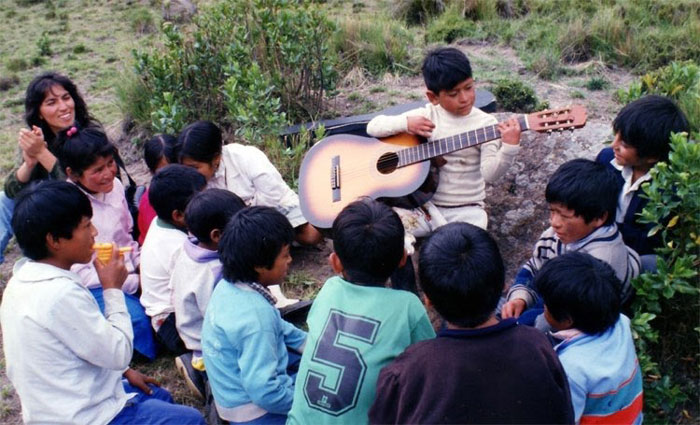

When I was invited to lead a series of workshops of my own design with the children of local schools, I saw an opportunity to contribute to a movement where children are respected and empowered, connected to nature and their ancestral cultures, and educated in lifeways that bring wellbeing and hope for their future and for life on the planet. We always went outside to play and explore with voice, sound, movement, storytelling, and games. Together we formed a safe space where all were co-creators and actors who could express themselves freely without censure or judgement. This process connected with and supported the gardening activities, and was my first experiment with AmaruArts.

Now, thanks to support from the Center for Nutrition Studies, AmaruArts is developing four full-day workshops for children and their mothers in rural Andean communities, in which participants will learn from local leaders about agriculture, health, and nutrition. Focus on medicinal foods will especially target immunological health and COVID-19. They will cook a large meal in a community kitchen while learning the benefits of healthy food preparation, and the nutritional benefits of local, organic food products and medicinal herbs.

Our vision of the future is of an empowered generation making a good living by protecting and restoring the integrity and diversity of life in the Andes. Over centuries, some of the world’s most productive and sustainable agricultural systems were developed in this region.[1] A 2018 study based on data from 60 farms in Cayambe, comparing agroforestry with conventional agriculture systems, found that the former provides significantly better conditions to support sustainable livelihoods for smallholder farmers.[2] For over two decades, at least two proteges of the PC project have established good livelihoods and raised their families from their small agroforestry farms in the communities of Chitachaka and Pisambilla.

Participatory community video is a powerful tool to help realize this vision. It can have positive effects both within a community and as a tool to project globally through social media. It is also a very youth-friendly medium. Youth can produce their own stories based on valuable community life experiences with an original perspective. They can document ancestral knowledge kept by the elders, farmers, and others, reflecting on their situations in local and global contexts, and challenging dominant narratives to propose creative alternatives. Community youth video-makers have the potential to become dynamic actors for change by documenting and sharing oral knowledge, facilitating reflection and debate, thus leading toward community empowerment. The value of who they are, and what they know and have is crucial for the survival of their lands and life forms, and of their role as stewards of the Andes.

The T. Colin Campbell Center for Nutrition Studies (CNS) is committed to increasing awareness of the extraordinary impact that food has on the health of our bodies, our communities, and our planet. In support of this commitment, CNS has created a Community Grant initiative to empower sustainable food-based initiatives around the world by providing grants to enable innovative start-ups and to propel the growth of existing initiatives. Please consider making a donation to this great cause. 100% of your donation will go to support initiatives like the one you just read about in this article.

Learn more about our Community Grant program.

References

- AValdez, F. (Ed.). 2006. Agricultura Ancestral, Camellones y Albarradas: Contexto social, usos y retos del pasado y del presente. Coloquio Agricultura Prehispánica sistemas basados en el drenaje y en la elevación de los suelos cultivados. Quito: Ediciones Abya-Yala. https://agrobolivia.files.wordpress.com/2011/04/02camellones.pdf.

- Córdova, R., N. Hogarth, M. Kanninen. 2018. Sustainability of smallholder livelihoods in the Ecuadorian Highlands: A comparison of agroforestry and conventional agriculture systems in the indigenous territory of Kayambi People. Land 7(2), 45: https://doi.org/10.3390/land7020045. “The results indicate that agroforestry systems contain greater agrobiodiversity; more diversified livelihoods; better land tenure security and household income; more diversified irrigation sources and less dependency on rainfall than conventional systems”. See also: www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/11/9/2623.

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits