The National Cancer Act of 1971, signed into law by President Nixon on December 23 of that year, is generally recognized as the beginning of the “war on cancer.”[1] It amended the Public Health Service Act of 1944 and mandated many significant changes to how the US dealt with cancer, including

- establishing the National Cancer Institute (NCI) as it exists today and increasing the authority of the director of the NCI;

- establishing the process by which NCI submits for its annual budget;

- creating the presidentially appointed National Cancer Advisory Board (NCAB); and

- providing funding for fifteen new NCI cancer research centers, data banks, and local control programs.

“The purpose of this Act,” in its own language, “[was] to enlarge the authorities of the National Cancer Institute and the National Institutes of Health in order to advance the national effort against cancer” (emphasis added).[1]

While others have located the so-called war’s roots earlier—focusing especially on the work of “socialite and publicist” Mary Lasker and the previous decade’s lobbying and funding work of her Citizens’ Committee for the Conquest of Cancer—there is no disputing that the 1971 legislation was supposed to mark a momentous shift in public perception and professional approaches to cancer research.[2] And though “[Nixon] did not use the phrase [war on cancer] . . . that day—perhaps because he had already declared a ‘war on narcotics’ only six months earlier . . . he did express the hope that the Act would be seen by history as ‘the most significant action taken during [his] Administration.’”

Compared to Other Wars

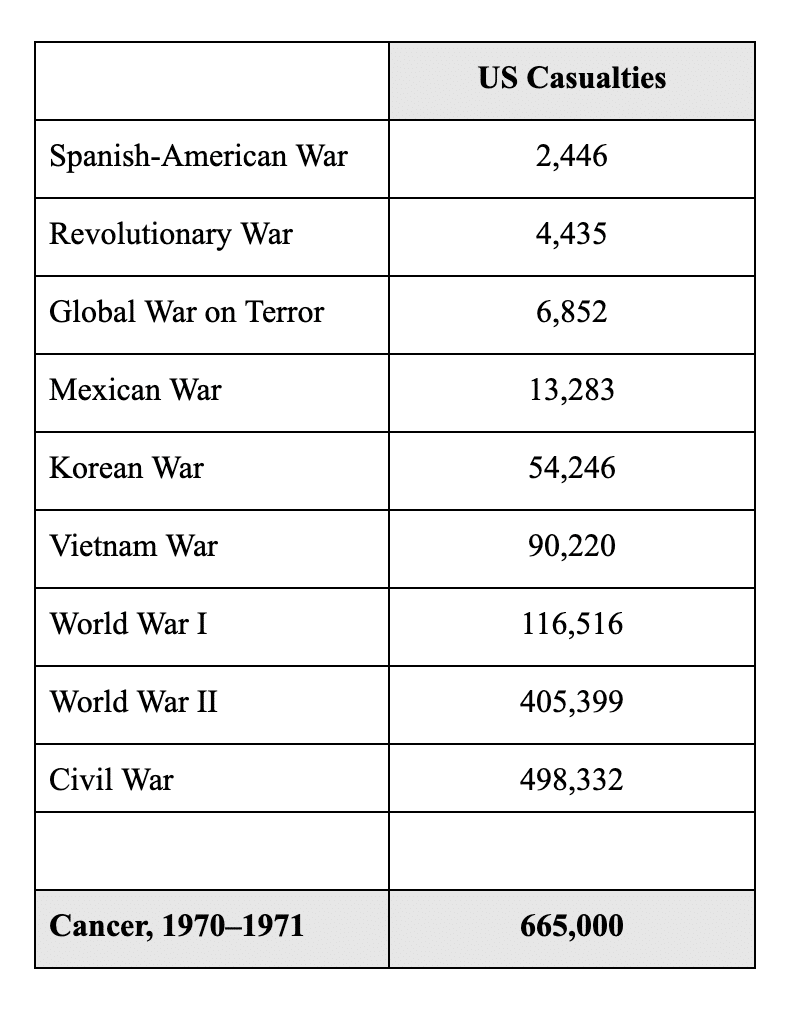

To Nixon’s point, victory in the war on cancer would certainly have been the most significant achievement of his administration, if victory had been achieved. By 1971, cancer was the nation’s second leading cause of death. To put the potential victory into perspective, Nixon compared cancer mortality to American deaths during World War II.

Whereas cancer killed about 665,000 Americans from 1970–1971, 405,399 Americans were killed throughout the entirety of World War II, which spanned a period almost twice as long.[3][4][5] Even the Civil War—the deadliest war in American history—killed far fewer people than cancer in the years 1970 and 1971.

If we embrace Nixon’s preferred metaphor, we would have to describe cancer in the years preceding the National Cancer Act of 1971 as the single most devastating, hostile adversary ever seen on any battlefield in American history.

In light of that devastation, the goals of the legislation seem valiant. And it is from this premise that cancer research, funding, and treatment has proceeded for the past half century. As described by one journalist in 2009, Nixon sought to find a cure by 1976, and after that, “the date for a cure . . . kept being put off.”[6] At the time of that article’s publication, NCI had spent more than $100 billion and expanded its army of employees to beyond four thousand.

So, Are We Winning the War?

The answer is more complex and nuanced than some would likely admit. Bold, contradicting claims are not hard to find. According to one review, the war “has had a profound impact and succeeded in fulfilling its mandate;” according to another, “We obviously haven’t won the war.”[7][8] Champions of the war point out that critics often fail to specify their criteria for judging success; however, many of the common critiques are difficult to answer for.

Almost fifteen years ago, at the World Oncology Forum in Switzerland, the question of whether the war on cancer has been a success was posed to numerous experts.[9]

The conclusion was, in general, no. Despite the introduction of hundreds of new anticancer drugs, including advanced therapies (so-called magic bullets) aimed at particular weapons in the enemy’s armamentarium, the consensus was that, for most forms of cancer, enduring disease-free responses are rare, and cures even rarer.

But even that does not tell the whole story. The extent to which researchers believe the war has failed depends on what they consider the war’s most important goals. Likewise, although some researchers are hopeful on account of the battles won—our understanding of the disease’s specific mechanisms has improved, funding has grown tremendously since 1971, and according to some, “Refined and potentially more-effective tactical strategies are being developed and tested”—these victories do not necessarily indicate overall success.[9]

Many cancer treatments, to the extent that they are really treatments, offer only small and short-term effects. They remain incredibly expensive. Likewise, the disease remains difficult to study, and more than fifty years later, it is still the second leading cause of death.

With Every Victory, Another Battle

As with many complex problems, even celebrated advances are accompanied by unexpected challenges. For example, advances in targeted therapy—that is, “drugs or other substances [used] to precisely identify and attack certain types of cancer cells” and “target genomically defined vulnerabilities in human tumors”—are lauded for potentially improving the precision and effectiveness of cancer treatment, but targeted therapy produces its own challenges.[10][11] Short of a cure, these are exactly the types of advances that researchers and the public would have hoped for fifty years ago. And yet, “the relatively rapid acquisition of resistance to such treatments . . . is observed in virtually all cases . . . and remains a substantial challenge to the clinical management of advanced cancers.”[11] Indeed, every cancer therapy is limited to some degree by the development of drug resistance, meaning that, for many researchers, the next step is to determine new strategies for predicting “eventual clinical drug resistance . . . and identifying novel resistance mechanisms.”[12]

Perhaps researchers will improve in their ability to predict drug resistance, and future treatments will yield better results, but in the meantime, the domino effect described above goes to show that even the most celebrated advances in the war on cancer have not been without challenges of their own. It’s no wonder that some are calling for a new strategy: “a military battlespace” approach that focuses far more attention on highly detailed “information about the enemy’s characteristics and armamentarium.”[9] Like the vast majority of treatments in the disease response system, this one places technology front and center, “to attack cancer with our increasingly powerful drugs and other weapons, with the use of increasingly advanced therapeutic strategies.”

In other words, the war on cancer may not be the raging success we hoped for, but now is not the time to abandon our battle stations. Rather, it’s time to upgrade the metaphor and our weaponry.

Beyond the “War”

In addition to the challenges outlined in the article cited above, there are other justifications for ditching the outdated metaphor. Some have warned of parallels between the the self-fulfilling military-industrial complex and the growing medical-industrial complex.[2] We should be cautious of the lack of prevention that occurs when so much money is being pumped into (and squeezed out of) the search for new weapons and “the distorted priorities of ‘war.’”[2] Others are concerned of the implications of constantly labeling patients as fighters, given that “most patients with advanced disease end that journey with loss of life” and no amount of fighting will change that fact.[13]

If we conclude that the best course of action is to abandon this notion of the war on cancer, and perhaps all similar wars, where does that leave us?[14] Where does it leave the challenges and goals outlined in the National Cancer Act of 1971? And which of these challenges and goals have we moved beyond in the year 2025?

Clearly, sadly, we have not “conquered” this disease yet. How far do we still have to go? In a future article, we’ll look more closely at the central question—are we winning the war on cancer?—and interpret trends in incidence, mortality, and survivorship data.

This article is part of a series on The Future of Nutrition: An Insider’s Look at the Science, Why We Keep Getting It Wrong, and How to Start Getting It Right by T. Colin Campbell, Ph.D.

References

- National Cancer Institute. National Cancer Act of 1971 (2016). https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/legislative/history/national-cancer-act-1971#declarations.

- Coleman, M. P. War on cancer and the influence of the medical-industrial complex. Journal of Cancer Policy 1(3,4), e31–e34 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcpo.2013.06.004

- Silverberg, E., Grant, R. N. Cancer statistics, 1970. American Cancer Society Journals. Online access: September 21, 2020. https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.3322/canjclin.20.1.10

- Wikipedia. United states military casualties of war. Online access: September 21, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_military_casualties_of_war

- Crigger, M., Santhanam, L. How many americans have died in u.s. wars? PBS News Hour. (2015, updated 2019). https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/many-americans-died-u-s-wars

- Kolata, G. Advances elusive in the drive to cure cancer. The New York Times (2009). https://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/24/health/policy/24cancer.html?_r=0

- DeVita, V. The ‘War on Cancer’ and its impact. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 1, 55 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncponc0036

- Harris, R. Why the war on cancer hasn’t been won. NPR (2015). https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2015/03/23/394132747/why-the-war-on-cancer-hasnt-been-won

- Hanahan, D. Rethinking the war on cancer. Lancet 383, 558-563 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62226-6

- American Cancer Society. Targeted Therapy. Online access: September 22, 2020. https://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/treatment-types/targeted-therapy.html

- Lackner, M. R., Wilson, T. R., Settleman, J. Mechanism of acquired resistance to targeted cancer therapies. Future Oncol 8 (8), 999–1014. doi: 10.2217/fon.12.86

- Garraway, L. A., Janne, P. A. Circumventing cancer drug resistance in the era of personalized medicine. Cancer Discov 2 (3), 214–226. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0012

- Ellis, L. M., Blanke C. D., Roach, N. Losing “losing the battle with cancer.” JAMA Oncol 1(1), 13–14 (2015). doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2014.188

- Miranda, D. M., Fernández G. L. ¿Contra qué se lucha cuando se lucha? Implicancias clínicas de la metáfora bélica en oncología [Clinical implications of the “war against cancer”]. Rev Med Chil 143(3), 352–357 (2015). doi:10.4067/S0034-98872015000300010

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits