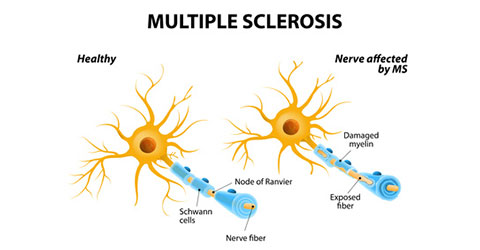

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a complex autoimmune disease meaning the body’s own immune system attacks itself. In MS the body attacks the central nervous system (CNS) meaning the brain and spinal cord. The words multiple sclerosis literally means many scars.

There are several different forms of MS presentation:

- Relapsing–remitting: Flare-ups of symptoms are accompanied with remission (often incomplete) resulting in accumulating disability. This is the most common form of MS.

- Primary progressive: There is no remission and the disease progresses from the outset.

- Secondary progressive: At diagnosis, the disease is relapsing-remitting but over time, there is progression to a more severe form.

- Benign: No or little evidence of accumulating disability. This is a rare form of MS and experts debate whether it exists at all.

MS Symptoms

Because the brain and spinal cord have so much control over how the body functions, MS can cause many symptoms throughout the body, depending on where the scars occur. Major symptoms include:

- Sensory change in extremities

- Optic neuritis

- Motor symptoms including weakness, spasm, and paraplegia

- Diplopia or internuclear ophthalmoplegia

- Gait (walking) difficulties

- Bladder/bowel dysfunction, vertigo, or pain

Other vague symptoms, such as fatigue or cognitive difficulty may become prominent with time and may correlate with the pathological progression.

What is the Cause of MS?

MS is a complex disease with many contributing factors. Therefore, the exact causes(s) of MS remains unknown. It is known that there are genetics factors and environmental factors. The genetic factors have been estimated to contribute about 25% to MS[1]. This is good news! 75% of MS risk is environmental, which means we can potentially alter our environment and hence the risk of getting MS or of MS getting worse. There are many environmental factors which are of interest in MS, including stress, infections, sunshine and vitamin D. But what about nutrition?

Plant-Based Diet and MS

Research dating back to the 1940s demonstrated that MS rates dropped during WWII. Interestingly, MS rates increased after the war. Some scientists and neurologists thought that rationing of foods may have contributed to this. Therefore, studies were designed to see if there was a link between rationed foods (butter, cheese, meat, etc.) and MS rates/severity.

In two studies, published just after WWII, a direct relationship between MS rates and saturated fat intake was reported in Norway[2][3]. Several later studies reported similar findings in Mexico[4] and Israel[5]. A study in 1974 involving 20 countries reported higher MS rates were associated with higher intake of meat, eggs, milk, butter, sugar and fat overall[6]. Following this was a very interesting article published in 1986 titled: Multiple sclerosis, latitude and dietary fat: is pork the missing link? This study again demonstrated a very significant link between MS rates and high fat intakes, and specifically pork consumption[7].

Three more advanced studies were published in the 1990s. A large, American study looked at many aspects of lifestyle (46 in total) in relation to MS. The two most important factors were high meat consumption and a diet high in dairy/low in fish[8]. This was followed by one of the largest studies to date, which involved 36 countries. Once again, high dietary fat and particularly saturated fat (meat, cheese, butter etc.) were strongly associated with MS[9].

These two studies were followed by a study from Canada which reported that those who had MS ate more calories and more animal fat than those who didn’t get MS. In addition, those who got MS tended to consume less vegetable protein (nuts, legumes, etc.), less fiber (all unrefined plants), less vitamin C and potassium (fresh fruits and vegetables)[10]. A recent study, this time in children with MS, recruited from 11 regions throughout the USA, demonstrated that each 10% increase in total fat consumption was associated with a 56% increase in relapse risk. Each 10% increase in saturated fat consumption was associated with a massive 237% increase in relapse risk. Conversely, each cup of vegetables was associated with a 50% decreased risk of relapse[11].

Further evidence comes from multiple studies demonstrating higher concentrations of saturated fat and lower concentration of unsaturated fat in red blood cells of those with MS compared to those without MS[12]. Similarly, studies dating back as far 1963 demonstrate higher concentrations of saturated fat in brain tissue of those with MS compared to those without MS[13]. Additionally, there are a series of studies which have demonstrated lower antioxidant levels in the blood of those with MS compared to those without MS[14]. Major sources of antioxidants are fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, and herbs/spices.

All of these studies are observational. Although they are both interesting and consistent, it is possible that being diagnosed with MS could cause somebody to change their diet and eat more meat, butter, cheese, etc. Stronger evidence comes from trials where participants actually changed their dietary habits and researchers examined the effect on MS rates/severity. Unfortunately, there is a lack of these trials but importantly, the trials that do exist report similar findings and are consistent with the studies I’ve introduced above. We will now explore these trials.

Enter Dr. Roy Swank, a neurologist who published almost 300 scientific papers, worked at several leading neurology institutes (until age 94) and lived to be 99! Swank was one of the first to think there was a connection between diet, specifically saturated animal fat, and MS. As such, he conducted some of the early studies associating MS rates with saturated animal fat intake[2][3]. Based on his own research and his own ideas, Swank was the first to put this association to the test. Swank recruited a group of 144 people with MS and asked them all to follow a very low saturated fat diet (15g/day, which is equivalent to 1.5 ounces of cheddar cheese or 1.5 pints of milk). Some people stuck with the diet (compliant) and some did not (non-compliant). Swank published his results 3.5 years, 5 years, 7 years, 20 years, 34 years and 50 years after the study began. This alone is a remarkable achievement – most dietary studies last weeks or months! Further, Swank published in some of the most prominent medical journals. The results showed that for those who complied with the low saturated fat diet, 95% remained physically active. However, for those who did not comply with the diet, only 7% remained physically active. 20% died from MS in the compliant group whereas 80% of those who did not comply with the diet died of MS causes. Regardless of disability at the start of the trial, those who stuck to the diet did not get significantly worse![15][16]

Writing about Swank’s work in the Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences, one radiologist wrote: “The results of his 34-year study published in The Lancet in 1990 remain the most effective treatment of multiple sclerosis ever reported in the peer review literature”[17].

There is a lack of dietary trials in MS but Swank’s work does not stand alone. A three year trial in the UK called Action into Research in MS (ARMS) demonstrated that those with MS who were able to decrease saturated fat while increasing polyunsaturated fat and antioxidants did not deteriorate while those who didn’t change their diet did deteriorate[18]. Two small, more recent trials demonstrated decreased flare-ups and disability when those with MS decreased their saturated fat intake and increased their omega-3 intake[19][20]. A more recent, ambitious trial was designed by Dr. John McDougall and the Department of Neurology at Oregon University (where Swank did a lot of work) to compare a low fat, plant-based diet to a standard diet. This one year trial did not find any differences in brain MRI outcomes, number of MS relapses or disability. However, the plant-based group did have reductions in body weight, cholesterol and fatigue[21].

In recent years, a group in Australia led by Professor George Jelinek (who himself has MS) conducted five day education sessions for those with MS. The education is similar to the Ornish style program: smoking cessation, daily meditation, exercise and sun exposure/vitamin D supplementation coupled with a mostly plant-based diet. Research on these programs has demonstrated improvements in quality of life one year and five years after these five day education sessions[22][23].

How Could Nutrition Contribute to MS?

We’ve already mentioned that MS is a complex, autoimmune disease. Avoiding smoking, exercising, stress reduction techniques as well as adequate sunshine and vitamin D all seem important. Additionally, nutrition does seem to be important for MS prevention and treatment. The existing evidence regarding nutrition and MS is consistent and demonstrates a link between diets high in saturated animal fat and MS. Evidence also supports a whole foods, plant-based diet to decrease MS severity.

There are multiple mechanisms by which a whole foods, plant-based diet could be beneficial for preventing and treating MS including changing the gut microbiome and the immune system, decreasing oxidative stress and inflammation and increasing blood flow around the body, including to the brain.

A beneficial effect of a plant-based diet on MS has not been conclusively proven. This would require several large, expensive and lengthy randomised, controlled trials. This is why neurologists, dietitians and MS Societies do not routinely recommend a plant-based diet. However, there are several interesting trials ongoing or being planned. While we wait for science to progress, based on consistent and extensive evidence, a whole foods, plant-based diet seems appropriate for those with MS or at risk of MS. As someone with MS, it is what I eat and what I recommend to my MS patients.

Read about Dr. Kerley’s personal experience with MS: From Scared School Boy with MS to Doctor of Nutrition

References

- Davidson A, Diamond B. Autoimmune diseases. N Engl J Med. 2001 Aug 2;345(5):340-50. Review.

- Swank, R.L. Multiple sclerosis (a correlation of its incidence with dietary fat) . Am J Med Sci. 1950;220:421.

- Swank, R.L. et al, Multiple sclerosis in rural Norway (its geographic and occupational incidence in relation to nutrition) . N Engl J Med. 1952;246:721.

- Alter, M. Multiple sclerosis in Mexico. Arch Neurol. 1970;23:451.

- Leibowitz, U., Kahana, E., Alter, M. The changing frequency of multiple sclerosis in Israel. Arch Neurol. 1973;29:107.

- Knox EG. Foods and diseases. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1977 Jun;31(2):71-80.

- Nanji AA, Narod S. Multiple sclerosis, latitude and dietary fat: is pork the missing link? Med Hypotheses. 1986 Jul;20(3):279-82.

- Lauer K. The risk of multiple sclerosis in the U.S.A. in relation to sociogeographic features: a factor-analytic study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994 Jan;47(1):43-8.

- Esparza ML, Sasaki S, Kesteloot H. Nutrition, latitude, and multiple sclerosis mortality: an ecologic study. Am J Epidemiol. 1995 Oct 1;142(7):733-7.

- Ghadirian P, Jain M, Ducic S, Shatenstein B, Morisset R. Nutritional factors in the aetiology of multiple sclerosis: a case-control study in Montreal, Canada. Int J Epidemiol. 1998 Oct;27(5):845-52.

- Azary S, Schreiner T, Graves J, Waldman A, Belman A, Guttman BW, Aaen G, Tillema JM, Mar S, Hart J, Ness J, Harris Y, Krupp L, Gorman M, Benson L, Rodriguez M, Chitnis T, Rose J, Barcellos LF, Lotze T, Carmichael SL, Roalstad S, Casper CT, Waubant E. Contribution of dietary intake to relapse rate in early paediatric multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017 Oct 9. pii: jnnp-2017-315936.

- Hon GM, Hassan MS, van Rensburg SJ, Abel S, van Jaarsveld P, Erasmus RT, Matsha T. Red blood cell membrane fluidity in the etiology of multiple sclerosis. J Membr Biol. 2009 Dec;232(1-3):25-34.

- BAKER RW, THOMPSON RH, ZILKHA KJ. Fatty-acid composition of brain lecithins in multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1963 Jan 5;1(7271):26-7.

- Socha K, Kochanowicz J, Karpińska E, Soroczyńska J, Jakoniuk M, Mariak Z, Borawska MH. Dietary habits and selenium, glutathione peroxidase and total antioxidant status in the serum of patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Nutr J. 2014 Jun 18;13:62.

- Swank RL, Goodwin J. Review of MS patient survival on a Swank low saturated fat diet. Nutrition. 2003 Feb;19(2):161-2.

- Kadoch MA. Is the treatment of multiple sclerosis headed in the wrong direction? Can J Neurol Sci. 2012 May;39(3):405.

- Fitzgerald G, Harbige LS, Forti A, Crawford MA. The effect of nutritional counselling on diet and plasma EFA status in multiple sclerosis patients over 3 years. Hum Nutr Appl Nutr. 1987 Oct;41(5):297-310.

- Nordvik I, Myhr KM, Nyland H, Bjerve KS. Effect of dietary advice and n-3 supplementation in newly diagnosed MS patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 2000 Sep;102(3):143-9.

- Weinstock-Guttman B, Baier M, Park Y, Feichter J, Lee-Kwen P, Gallagher E, Venkatraman J, Meksawan K, Deinehert S, Pendergast D, Awad AB, Ramanathan M, Munschauer F, Rudick R. Low fat dietary intervention with omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in multiple sclerosis patients. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2005 Nov;73(5):397-404.

- Yadav V, Marracci G, Kim E, Spain R, Cameron M, Overs S, Riddehough A, Li DK, McDougall J, Lovera J, Murchison C, Bourdette D. Low-fat, plant-based diet in multiple sclerosis: A randomized controlled trial. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016 Sep;9:80-90.

- Li MP, Jelinek GA, Weiland TJ, Mackinlay CA, Dye S, Gawler I. Effect of a residential retreat promoting lifestyle modifications on health-related quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis. Qual Prim Care. 2010;18(6):379-89.

- Hadgkiss EJ, Jelinek GA, Weiland TJ, Rumbold G, Mackinlay CA, Gutbrod S, Gawler I. Health-related quality of life outcomes at 1 and 5 years after a residential retreat promoting lifestyle modification for people with multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2013 Feb;34(2):187-95.

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits