Industrial agriculture, especially animal agriculture, is at the center of humanity’s most urgent environmental challenges: deforestation, biodiversity loss, mass extinction, natural resource scarcity, greenhouse gas emissions, and widespread pollution, from the air we breathe to oceans and waterways. It’s difficult to imagine any other human behavior with such a capacity for destruction, except for nuclear warfare; what does it say about our capacity for survival or even prudence when our preferred method for feeding ourselves is also destroying planetwide environmental life support systems?

Does industrial agriculture at least succeed in other ways? The 20th century’s misappropriately named green revolution promised that industrialized agriculture would at least succeed in increasing total yields and feeding people more efficiently—a goal that becomes more important every day that the global population continues to rise (estimates say it will increase another 35% by 2050)[1]—but do we achieve this promised efficiency? Not as long as we continue to choose animal-based foods.

What Percentage of Food Is Fed Directly to Humans?

For all the talk about the need to increase food production, it might surprise you that we already produce far more crops than are needed to feed today’s population.

According to research published in 2018, “the current production of crops is sufficient to provide enough food for the projected global population of 9.7 billion in 2050,” but radical changes are necessary to ensure that this crop production effectively feeds people.[2] These changes include “replacing most meat and dairy with plant-based alternatives, and greater acceptance of human-edible crops currently fed to animals.” The authors conclude, “Our analysis finds no nutritional case for feeding human-edible crops to animals, which reduces calorie and protein supplies.”

To give you an idea of how effective shifting to a plant-based diet could be, consider how much current crop production directly feeds humans—only 55 percent!—with “the rest fed to livestock (about 36 percent) or turned into biofuels and industrial products (roughly 9 percent).”[1]

But Humans Can’t Eat Livestock Feed, Right?

The article cited above specifies the human-edible crops fed to animals. Apologists for the animal foods industry are keen to emphasize this distinction because it turns out that most of the feed livestock consume—as much as 86 percent—is not edible for human consumption.[3] They argue that livestock are good sources of nutrition because they convert non-edible materials into edible meat.

The flaw in this argument is obvious: We don’t need to set aside so much land or produce so much non-edible biomass in the first place. It’s not as if the food fed to livestock is destined to either A) become feed or B) go wasted. To focus so much on this 86 percent figure, as if non-edible livestock feed will exist regardless of what we choose to eat, is a false dilemma fallacy. It ignores many other possibilities, especially transitioning non-edible crop production into edible crops.

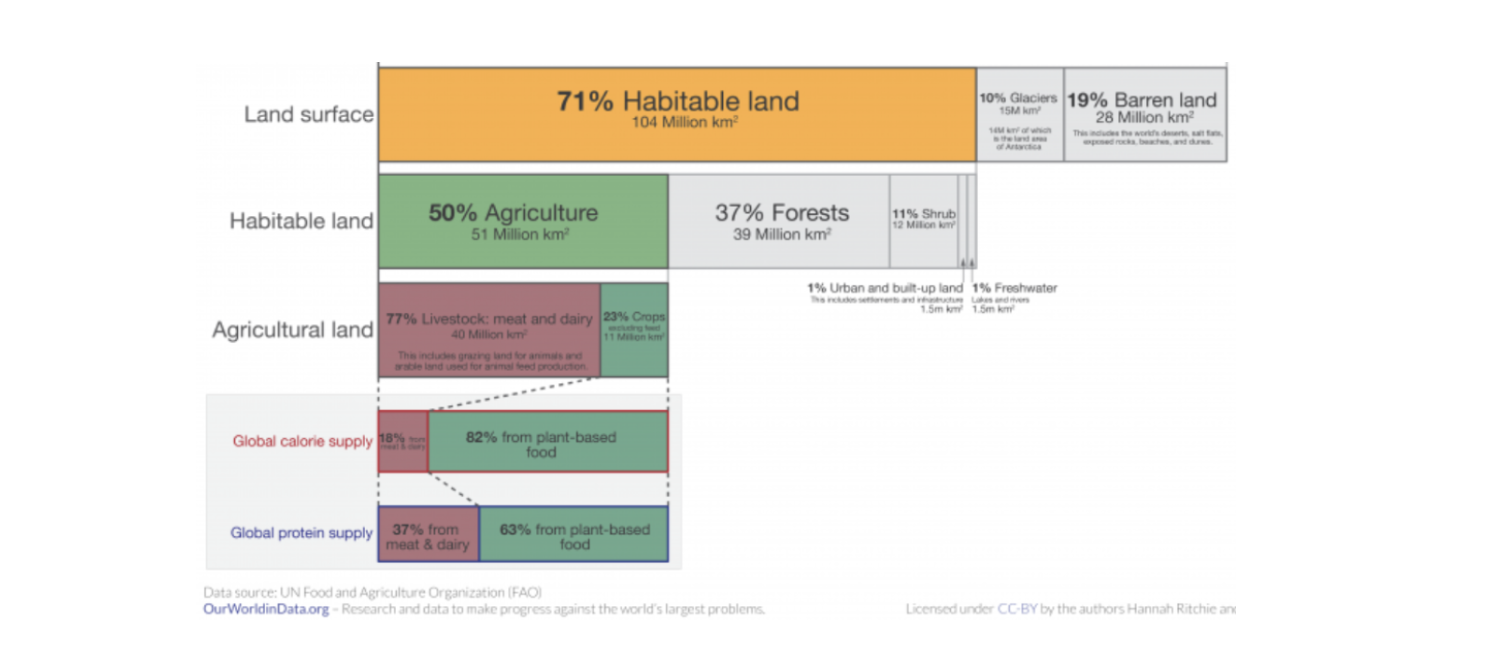

Even if a significant proportion of grazing land is unsuitable for growing crops, the amount we could convert to cropland is more than sufficient to drastically increase global food supplies. Consider how much food eaten worldwide already comes from less than a quarter of all agricultural land: more than 80 percent of the total calorie supply comes from plant-based foods.

Researchers estimate that about 700 million hectares of grasslands currently used for livestock could be converted to cropland.[3] That’s about 1.73 billion acres of cropland—an area nearly as large as the 48 contiguous United States. Now, add to that the crops that are edible for humans plus the cropland currently producing non-edible feed. With such an increase in food supplies, we could easily support a growing population while also rewilding grasslands unsuitable for growing food, promoting the return of biodiversity and facilitating carbon sequestration.

Call It What It Is: Wasted Food

The wastefulness of producing animal-based foods has been well-known for decades. More than 25 years ago, Cornell ecologist David Pimental reported on the nearly 800 million people who could be fed the grain given to livestock.[4] And that doesn’t account for the additional benefits of transitioning toward sustainable plant-based agricultural systems.

You might wonder about food waste. If we could reduce food waste, might the profligacy inherent to our food production systems be less consequential?

There’s no question that food waste is a huge issue. Estimates show that one-fourth of food calories are lost or wasted before consumption.[1] We should advocate for eliminating this waste as much as possible. But in the meantime, shouldn’t the food waste discourse also be expanded to include a more thorough critique of animal agriculture? If the inefficiencies of this system are as reckless as the data suggest, then shouldn’t the edible animal foods in our fridge receive at least as much scrutiny as the spoiled veggies?

References

- Foley J. A five-step plan to feed the world. National Geographic; The Future of Food. Accessed October 5, 2023. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/foodfeatures/feeding-9-billion/

- Berners-Lee M, Kennelly C, Watson R, Hewitt CN. Current global food production is sufficient to meet human nutritional needs in 2050 provided there is radical societal adaptation. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene. 1 January 2018; 6 52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.310

- Mottet A, de Haan C, Falcucci A, Tempio G, Opio C, Gerber P. Livestock: On our plates or eating at our table? A new analysis of the feed/food debate. Global Food Security; September 2017:14(1-8). doi:10.1016/j.gfs.2017.01.001

- Cornell Chronicle. U.S. could feed 800 million people with grain that livestock eat, Cornell ecologist advises animal scientists. August 7, 1997. https://news.cornell.edu/stories/1997/08/us-could-feed-800-million-people-grain-livestock-eat

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits