Although we all know on some level that the state of health in the US is not in a good place, it can be difficult to quantify exactly what that looks like. There are multiple layers of failure, and some are more immediately apparent than others. The physical challenges of living with disease are the most obvious. The financial repercussions are also widely accepted; most people know that our healthcare system is overburdened, if not outright broken, and that medical expenses are a top cause of bankruptcy. However, not enough is said about how all of this generally relates to our psychological health:

How does it feel to live in a society in which

- chronic disease is commonplace,[1]

- years if not decades of accompanying medical interventions, mostly pharmaceutical, are accepted as not only normal but also often inevitable,[2]

- we seemingly cannot afford to manage these diseases, so much so that they threaten to overwhelm the national economy,[3]

- medical expenses are among the most common causes of personal financial crises, and[4]

- the profits enjoyed by a small minority are seemingly more protected than the health of the masses?

How might these and other realities of health in the US impact our collective psyche, our trust in the systems purporting to address these challenges, and our outlook on the future? How do we cope?

Taking a Longer, Wider View

Before more closely examining the psychological damage inflicted by disease, it may be helpful to consider a few specific examples that illustrate why the current state of health in the US needs to be addressed.

In a previous article exploring life expectancy trends, we found that global life expectancy has trended upward (and continues to trend upward) in the long term because of basic medical advances, accessibility to key resources, and decreasing childhood mortality. However, when we analyze only wealthier countries—where these gains have already been realized to a greater extent—we see that the US lags behind.

In the US, life expectancy has stagnated or even declined in recent years. While the gap between the US and other wealthier countries was worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic, these trends preceded the pandemic.[5] Life expectancy at birth in the US is more than three years shorter than the average of high-income countries.[6] Average healthy life expectancy (HALE) is more than four years shorter within the same group.[7] Whereas three or four years might not sound like a lot in an individual life, in a population of more than 330 million, this amounts to an astronomical number of lost years of life.

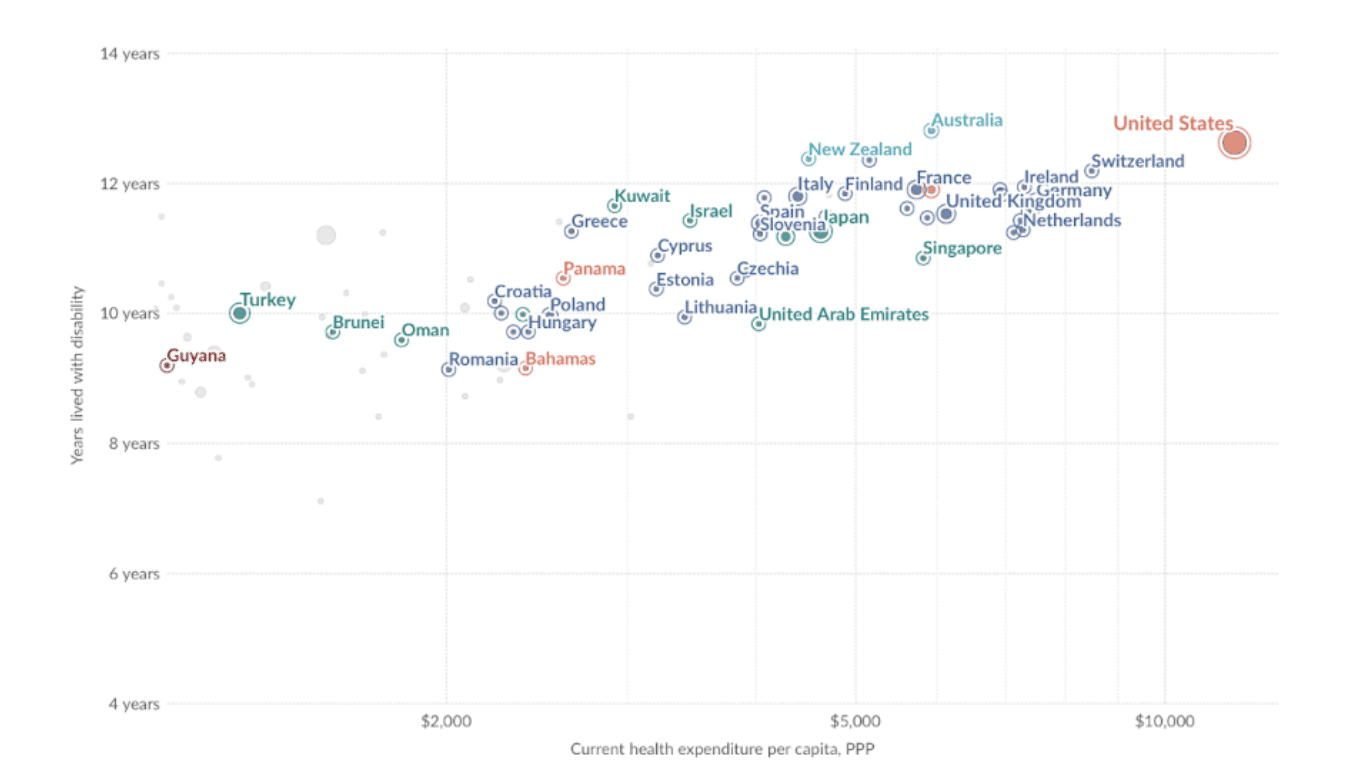

Like HALE, the metric years lived with disability gives a more nuanced indication of overall quality of life, not only length of life. And again, for this metric, the US does not compare favorably with other high-income nations, despite spending the most on health care (Chart 1).[8] As cited in The Future of Nutrition: “Fifty-five percent of Americans take prescription drugs—four per day, on average—and many of these people, as well as many of the minority who do not regularly take prescription drugs, take dietary supplements, too.” All of this reflects what Dr. Campbell correctly describes as not the successful pursuit of health but rather “the normalcy of disease.”

Chart 1: “Years lived with disability vs health expenditure per capita, 2021” (Top 50 countries by GDP per capita)

Data source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), Global Burden of Disease (2024); Multiple sources compiled by World Bank (2024); Visualization by OurWorldinData.org[8] CC BY

Chronic Disease and Depression, Stress, and Quality of Life

The relationship between chronic disease and depression is strong and bidirectional: people with chronic disease are likelier to be depressed, and depressed individuals are likelier to develop chronic diseases.[9] The National Institute of Mental Health of the NIH specifically highlights the link between depression and several of our deadliest, costliest diseases, including heart disease, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease. For example, patients with rheumatoid arthritis are on average as much as six times more likely to suffer from a mood disorder compared to the rest of the population.[10]

Unsurprisingly, the same bidirectional relationship exists between disease and stress. What is more interesting is how chronic stress produces “macroscopic changes in certain brain areas, consisting of volume variations and physical modifications of neuronal networks.”[11] Stress, in other words, transforms the brain. This observation is well supported by various types of evidence, including brain imaging studies and the postmortem examination of depressed individuals.

Chronic disease also affects the psychological well-being of those not directly suffering from the disease, as many caregivers can attest to. Caregivers suffer from high rates of chronic stress and depression, making them susceptible to poor health outcomes themselves. Indeed, as the authors of a 2008 review write, “Caregiving fits the formula for chronic stress so well that it is used as a model for studying the health effects of chronic stress.”[12]

Finally, psychological well-being during times of disease is obviously hugely important in determining overall quality of life. In a study of quality of life in heart disease patients who received a left ventricular assist device, researchers found that psychological factors were the strongest predictors of quality of life satisfaction.[13] Poor psychological health is predictive of lower quality of life satisfaction, which in turn could contribute to poor health outcomes and even the progression of disease.

This raises a troubling question: if disease, especially chronic disease, is known to undermine psychological health by increasing stress, contributing to depression, and limiting a patient’s ability to function, how does one avoid a downward spiral of interconnected physical and psychological suffering?

Solutions

Patients can and do adopt many coping strategies supportive of better psychological health, even in the most dire circumstances. Researchers have found that religious or spiritual beliefs and activities help improve coping with terminal illness.[14] This should come as no surprise, and it’s also relevant to nonterminal patients suffering from chronic diseases. Likewise and again not surprisingly, patients with a strong, positive relationship with their physician are likelier to report a higher quality of life.

This suggests that physicians, not only patients, must be better equipped to deal with the psychological challenges inherent to disease treatment. A study on this subject published in 1995 concludes: “Clinicians who felt insufficiently trained in communication and management skills had significantly higher levels of distress than those who felt sufficiently trained. If ‘burnout’ and psychiatric disorder among cancer clinicians are to be reduced, increased resources will be required to lessen overload and to improve training in communication and management skills.”[15] I can only hope that these increased resources have been provided to physicians in the intervening decades.

Ultimately, however, there is only one way to ensure a complete break from the vicious cycle of chronic disease and psychological distress, and that is to stamp out chronic disease at its roots. Helping people understand that many chronic diseases can be prevented and even possibly reversed is hugely empowering, and this sense of empowerment can reinforce good mental health. How many people fully appreciate nutrition’s profound ability to control heart disease, diabetes, Alzheimer’s, cancer, and more? How many doctors are properly trained in this healing medicine? How well are we doing to get this message into the mainstream?

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “About chronic diseases” webpage, accessed January 14, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/chronic-disease/about/index.html

- Ho JY. Life Course Patterns of Prescription Drug Use in the United States. Demography. 2023;60(5):1549-1579. doi:10.1215/00703370-10965990

- Hacker K. The Burden of Chronic Disease [published correction appears in Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2024 Dec 13;9(1):100588. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2024.11.005]. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2024;8(1):112-119. Published 2024 Jan 20. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2023.08.005

- Slomski A. Chronic Disease Burden and Financial Problems Are Intertwined. JAMA. 2022;328(13):1288–1289. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.15440

- Rakshit S, McGough M, Amin K. How does U.S. life expectancy compare to other countries? Peterson-KFF. January 30, 2024. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/u-s-life-expectancy-compare-countries

- World Health Organization: Global Health Observatory. Life expectancy at birth (years). Accessed online January 14, 2024. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/life-expectancy-at-birth-(years)

- World Health Organization: Global Health Observatory. Healthy life expectancy (HALE) at birth (years). Accessed online January 14, 2024. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/gho-ghe-hale-healthy-life-expectancy-at-birth

- Our World in Data. Years lived with disability vs. health expenditure per capita, 2021. Data from IHME, Global Burden of Disease (2024).

- National Institute of Mental Health. Understanding the link between chronic disease and depression. Accessed online January 14, 2024. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/chronic-illness-mental-health

- Turner J, Kelly B. Emotional dimensions of chronic disease. West J Med. 2000;172(2):124-128. doi:10.1136/ewjm.172.2.124

- Mariotti A. The effects of chronic stress on health: new insights into the molecular mechanisms of brain-body communication. Future Sci OA. 2015;1(3):FSO23. Published 2015 Nov 1. doi:10.4155/fso.15.21

- Schulz R, Sherwood PR. Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(9 Suppl):23-27. doi:10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336406.45248.4c

- Grady KL, Meyer P, Mattea A, et al. Predictors of quality of life at 1 month after implantation of a left ventricular assist device. Am J Crit Care. 2002;11(4):345-352.

- Zhang B, Nilsson ME, Prigerson HG. Factors Important to Patients’ Quality of Life at the End of Life. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(15):1133–1142. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2364

- Ramirez AJ, Graham J, Richards MA, et al. Burnout and psychiatric disorder among cancer clinicians. Br J Cancer. 1995;71(6):1263-1269. doi:10.1038/bjc.1995.244

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits