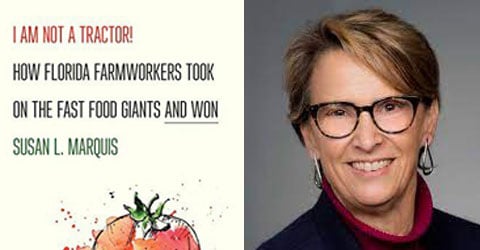

The following is an excerpt from I Am Not a Tractor! How Florida Farmworkers Took On the Fast Food Giants and Won (December 2017) by Susan L. Marquis. In the Center for Nutrition Studies’ upcoming Plant Forward Virtual Workshop Series, CIW staff member Cruz Salucio will share his insight on effective strategies for change in the food system.

Once CIW members stepped back and started to both see and understand the system as a whole—that the food chain led from workers to growers to the large corporate buyers—the necessary strategy became apparent. They stopped banging their heads against the wall the growers represented, looked outside the farm gate, and reset their target to the top of the chain.

The CIW’s objectives hadn’t changed: increase farm workers’ wages to a living wage; turn farm fields ridden with the dangers of violence, sexual harassment, and chemical poisoning into safe workplaces; and ensure that the workers “had a place at the table” when making decisions that affected their pay and safety. What was different was a profound change in perspective and strategy. The CIW’s target was now the major corporate buyers of tomatoes, the national fast-food chains and, eventually, grocery stores.

The CIW’s logic went something like this. The large corporate buyers—fast- food and grocery store chains—had the power and the money. Tomatoes were a small part of the chains’ costs. The growers had little leverage against McDonald’s, Taco Bell, Kroger, Giant, Walmart, and the like. The chains’ purchasing power, as workers saw in the article in the Packer, enabled them to push down the prices they paid the tomato growers. Lower prices for commodity tomatoes increased a profit margin that already dwarfed the margin the growers could ever hope to achieve. The Coalition’s logic said that the same power that made it possible to force the price of tomatoes down could also pull prices up to cover the cost of a wage increase for tomato pickers.

It was one thing to consider the possibility of using the buyers’ market power to bring prices up and another to know how to do it. Unions and advocacy groups have used consumer pressure before, a notable example being the United Farm Workers’ grape boycott of the 1960s and early 1970s. If the CIW could successfully pressure buyers to move prices up, what mechanism could they use to ensure the increase went to increasing workers’ wages, not just to the growers’ bottom lines?

The buyers’ power could be leveraged to change the system. Their purchasing power could be used to compel compliance with farmworkers’ human rights, and their resources could be used to increase worker pay.

Answering the first question required locating the CIW’s particular leverage point against these goliaths. What Greg Asbed realized was that the buyers’ strength, the power of their brands, was also their vulnerability. The large buyers’ brands, their reputation, was what brought customers to their stores. Customers went to a McDonald’s in Poughkeepsie not because they had read all the reviews and knew that was the best hamburger in town. They went to the McDonald’s store simply because it was McDonald’s. They knew the brand, knew what it promised, and knew it would deliver. Put the brand at risk, link it to a danger or unacceptable behavior, and the company and its shareholders were at risk. Food poisoning examples abound, but in the 1990s there were also examples related to labor concerns, most notably Nike’s use of cheap labor and sweatshops. The corporate buyers’ vulnerability could be exploited through consumers. The people who bought McDonald’s fries or Burger King’s Whopper were the force the CIW could use to counter the power of the corporations. If tomato growers were anonymous to consumers, and thus largely impervious to bad publicity, the opposite was true of the major buyers and their brands. Link that tomato on that Whopper to the abuse and poverty of farm workers, and consumers might join the Coalition’s fight.

Answering the second question, the mechanism for getting any price increase to go to workers’ wages went back to the conversations Greg Asbed and Laura Germino had with David Wang. To get to a living wage, tomato workers needed to be paid about 70¢ a bucket of tomatoes. Fighting for a nickel-per-bucket increase was not going to get the workers where they needed to be. In another Packer article, the CIW learned that the Florida Tomato Exchange, the industry group representing the tomato growers, assessed an industry wide surcharge to cover, for example, the cost of switching from one pesticide to another that was less toxic. Why couldn’t the CIW take the same targeted approach? This time, the “premium” would be for the workers. The CIW would hold the major buyers accountable for the low pay for farm workers and call for the chains to pay a premium of a “penny-per-pound” of tomatoes targeted to the workers. If they did so, worker wages could as much as double.

After months of discussions in the CIW’s weekly meetings, General Assembly meetings for all members, full-day strategy sessions with the newly established Central Comité, and investigations and reality checks with friends and allies, the major elements of the Coalition’s strategy fell into place. The buyers’ power could be leveraged to change the system. Their purchasing power could be used to compel compliance with farmworkers’ human rights, and their resources could be used to increase worker pay. The mechanism for increasing workers’ pay would be the surcharge or “premium” of a penny-per-pound increase in the price the buyers would pay for their tomatoes. Consumers could provide the power to force the change.

To hear more about this incredible story, you can register for the Plant Forward Virtual Workshop Series, where CIW staff worker Cruz Salucio will share his first-hand account of arriving in the United States from Guatemala, working under abusive conditions on farms in the United States, and transitioning into a full-time position with the Coalition of Immokalee Workers to fight for justice in the food system.

References

- Marquis, Susan L. “Chapter 3: Campaigning for Fair Food.” I Am Not a Tractor! How Florida Farmworkers Took on the Fast Food Giants and Won. Ithaca: ILR, an Imprint of Cornell UP, 2017. 54-55. Print.

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits