Colorectal cancer includes cancer that begins in the colon or rectum, which are often paired together because their effects are similar once the cancer has spread. In most cases, colorectal cancer begins with the growth of polyps on the inner lining of these organs.[1] The disease makes up a significant portion of the overall cancer burden in the US: [2]

- It is estimated to have killed more than 51,000 people in the US in 2019.

- It is the third deadliest cancer site for both men (after cancers of the lung & bronchus and prostate) and women (after cancers of the lung & bronchus and breast) in the US.

- It is the third most incident cancer site for both sexes in the US.

- One in twenty-three men and one in twenty-five women in the US will develop colorectal cancer during their lifetimes.

- Of the patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer between 2008 and 2014 in the US, one in three did not survive five years after diagnosis.

Signs and symptoms of the disease include rectal bleeding, persistent abdominal discomfort or pain, and weakness or fatigue, though many people, “experience no symptoms in the early stages of the disease.”[3]

The Good News

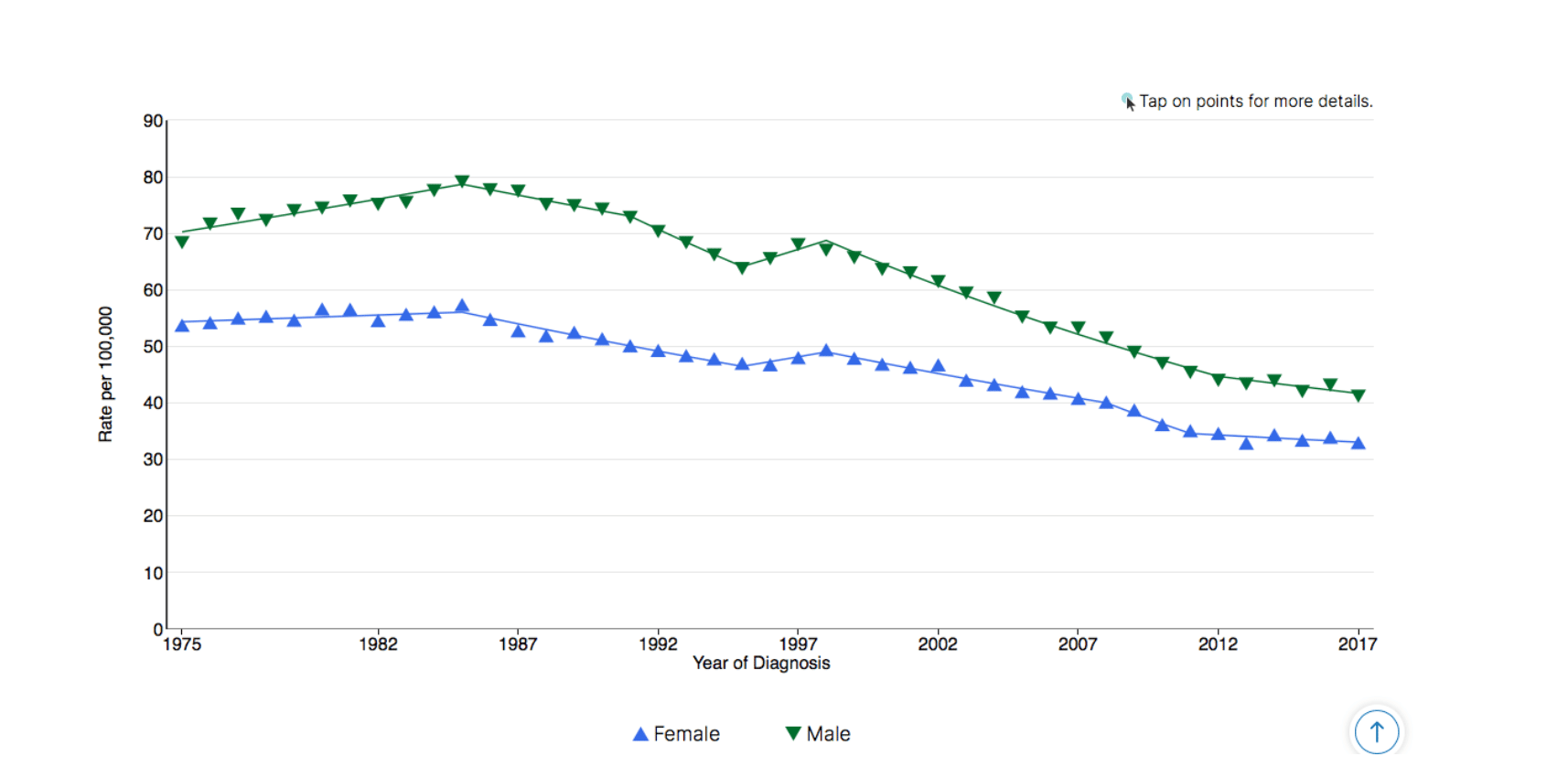

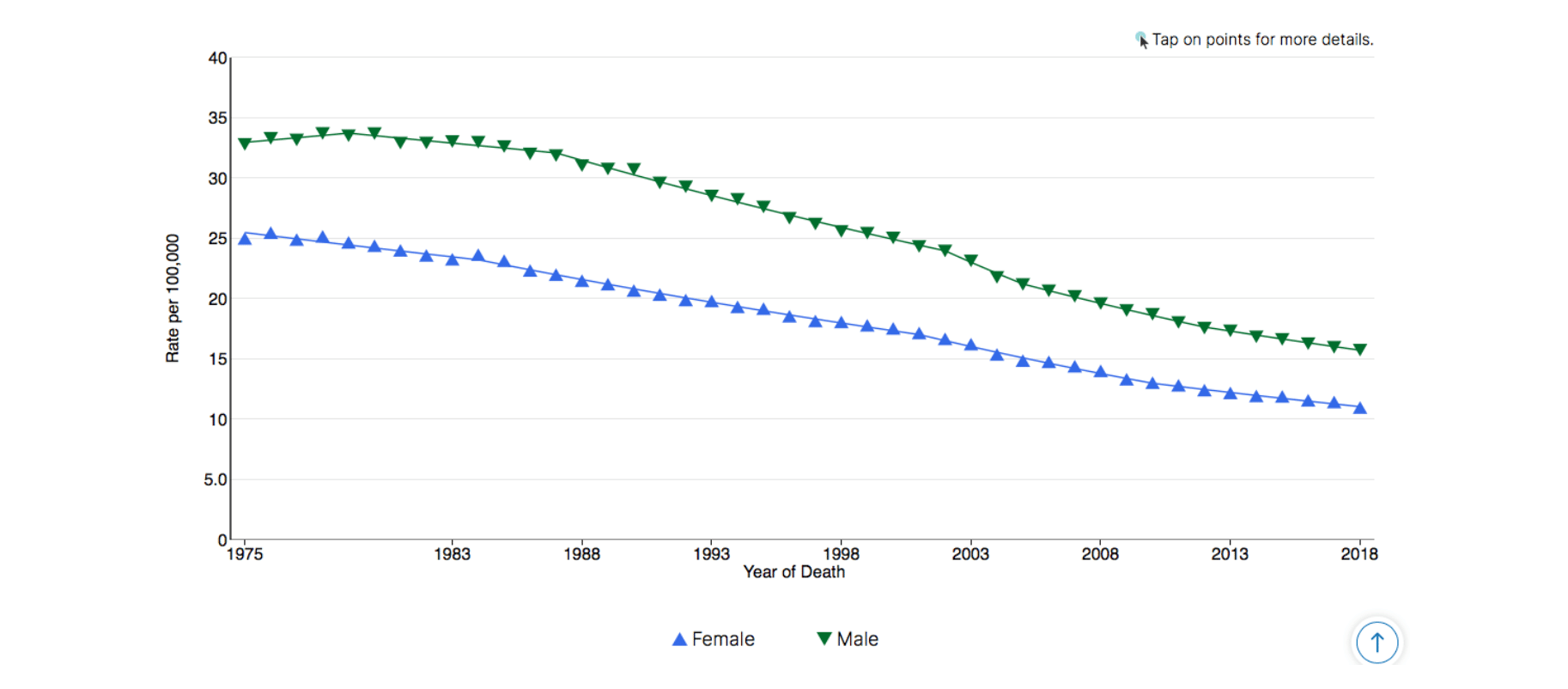

Colorectal cancer is one of the most improved cancer sites in the US in terms of long-term mortality and incidence rates.[4] Incidence rates for both sexes have dropped nearly 45 percent, from a peak of about 66 per 100,000 in 1985 to about 37 per 100,000 in 2017. Mortality rates have dropped even more—over 53 percent since 1975.

Colon and Rectum Cancer Long-Term Trends in SEER Age-Adjusted Incidence Rates, 1975–2017

Source: SEER*Explorer. SEER 9 areas[4]

Colon and Rectum Cancer Long-Term Trends in US Age-Adjusted Mortality Rates, 1975–2018

Source: SEER*Explorer. US Mortality Files, National Center for Health Statistics, CDC[4]

If we compare these trends to other cancer sites, as described in a previous article, it appears the US medical system has done a great job of addressing colorectal cancer. The 5-year death rate—about 33 percent for colorectal cancer diagnoses from 2008–2014—is still too high, but it’s a big improvement from the 50 percent rate of 1975–1977.[2]

This is victory, right?

Sort of. These figures only tell part of the story, and if there’s one thing public understanding of the “war on cancer” could benefit from, it is a more nuanced appreciation for how complex cancer is, and an appreciation for the fact that we still have a long way to go. Colorectal cancer, as an example of a “victory,” illustrates this point especially well.

Varying Rates, Even Within the US

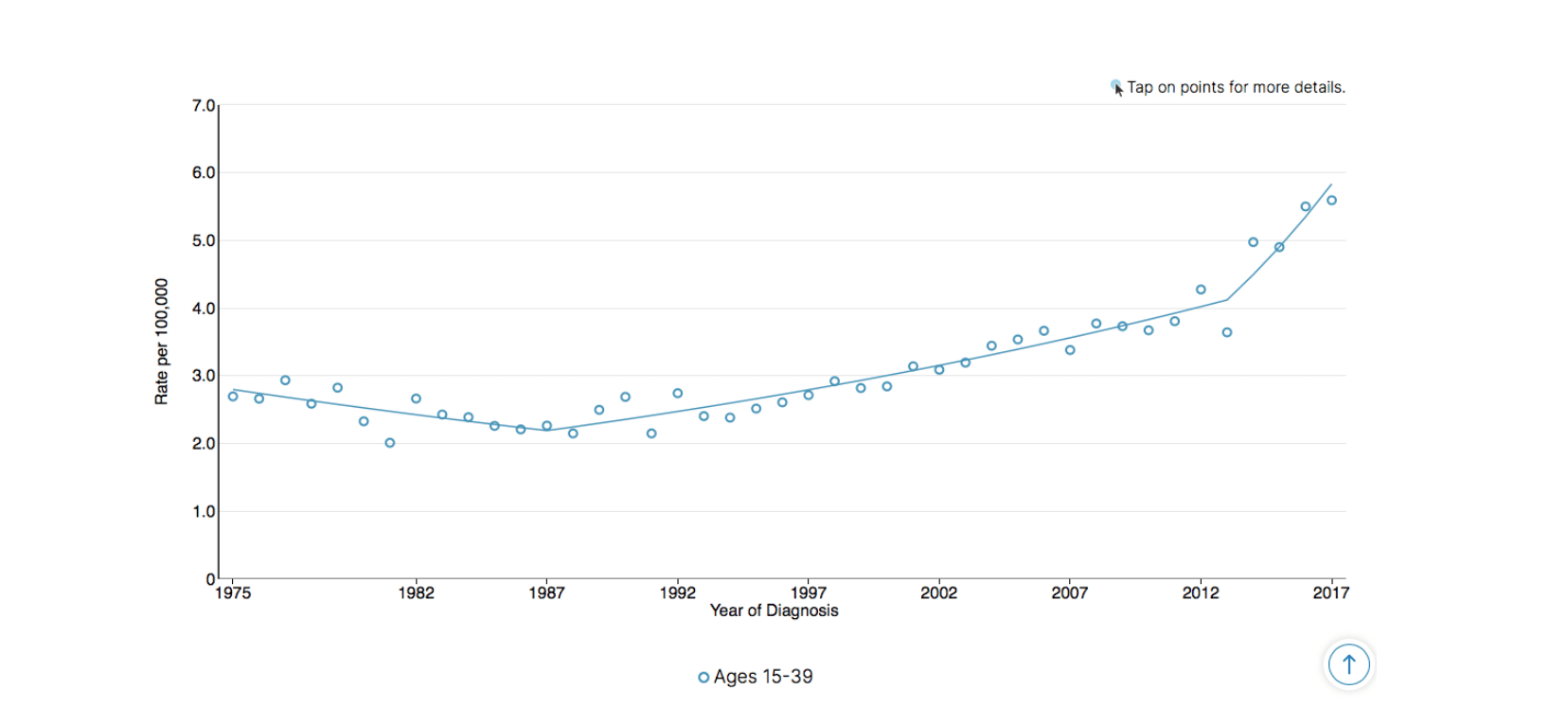

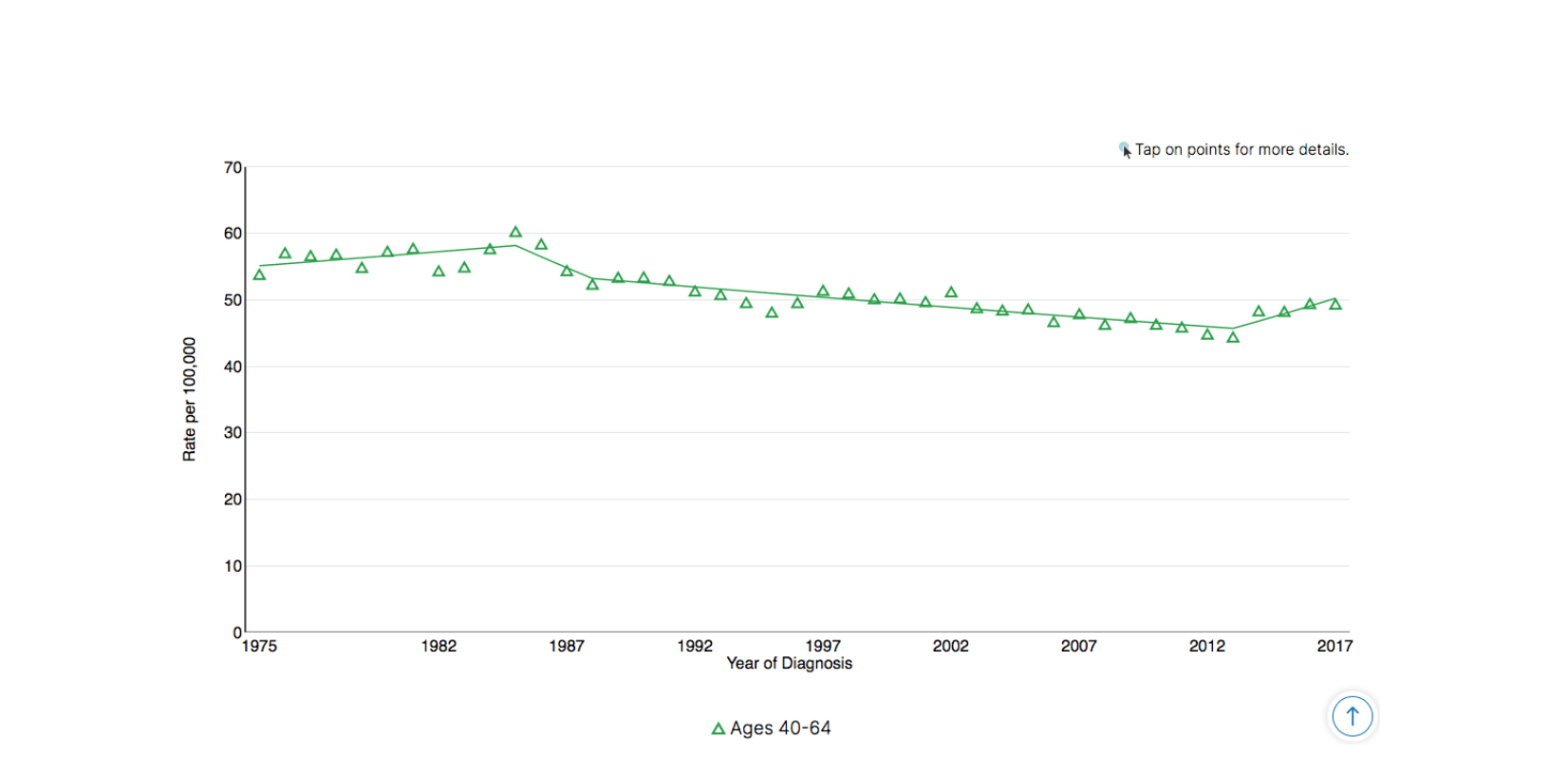

It’s difficult to generalize about the population as a whole using the overall incidence and mortality trends listed above because different demographic groups have benefited to varying degrees. Perhaps the most significant demographic discrepancies have to do with age. Take, for example, incidence:[5]

While those over 50 years of age have seen decreases in CRC incidence in the US over the past decades, those aged 20–49 years have actually seen a growing incidence… The incidence rates of CRC for ages 20–49 years was 9.3 per 100,000 in 1975 and now is up to 13.7 per 100,000 in 2015, a percentage change of 47.31%, whereas incidence rates in age groups 50 years and above has steadily decreased.

Colon and Rectum Cancer Long-Term Trends in SEER Age-Adjusted Incidence Rates, ages 15–39, 1975–2017

Source: SEER*Explorer. SEER 9 area[4]

Colon and Rectum Cancer Long-Term Trends in SEER Age-Adjusted Incidence Rates, ages 40–64, 1975–2017

Source: SEER*Explorer. SEER 9 area[4]

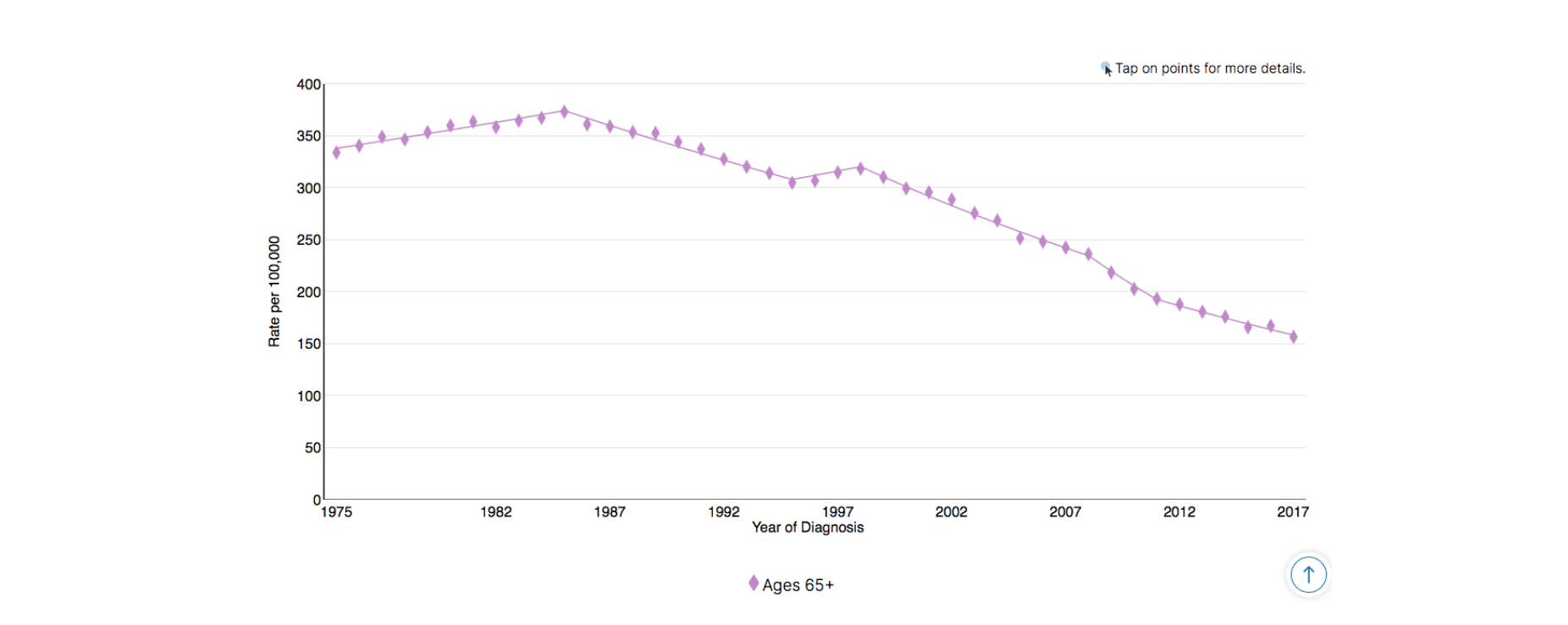

Colon and Rectum Cancer Long-Term Trends in SEER Age-Adjusted Incidence Rates, ages 65+, 1975–2017

Source: SEER*Explorer. SEER 9 area[4]

Because there are many more cases of colorectal cancer in the older age groups, decreased incidence among those groups contributes much more significantly to overall incidence trends. Decreased incidence among older age groups profoundly impacts overall incidence, and those improvements are worth applauding. But the fact that young people in the US are increasingly being diagnosed with colorectal cancer is also concerning, especially since mortality rates for the youngest have also worsened in the last three decades.[4]

Other considerations:[4]

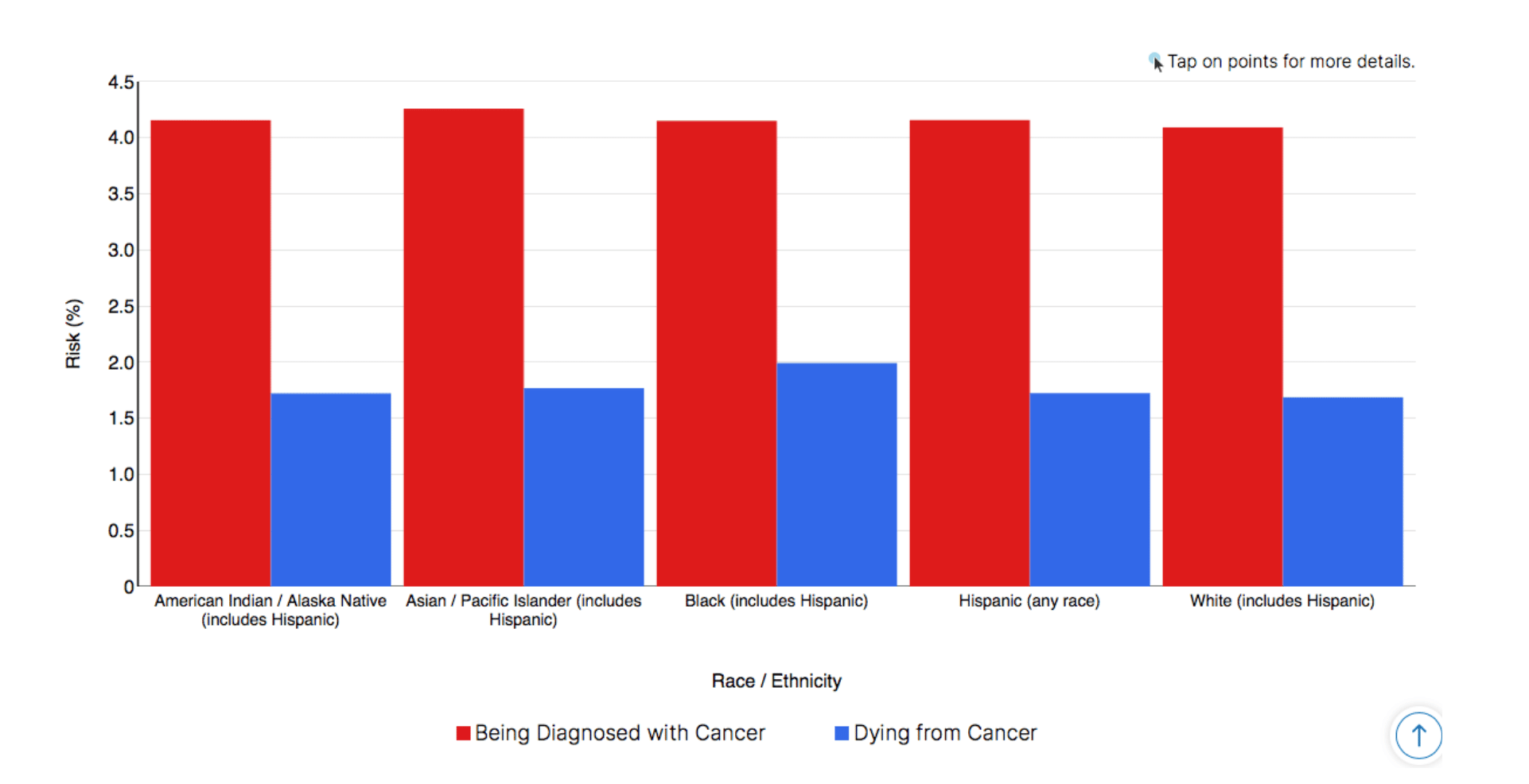

- Men remain more likely than women both to be diagnosed with colorectal cancer and to die from colorectal cancer, except in the case of American Indians, for which women are more likely to be diagnosed but less likely to die than men.

- Whites (including Hispanics) are less likely to be diagnosed and die of colorectal cancer than every other racial or ethnic group.

- Blacks (including Hispanics) are the most likely to die of colorectal cancer, for both sexes, but are less likely to be diagnosed than American Indians/Alaskan Natives (including Hispanics), Asians/Pacific Islanders (including Hispanics), and Hispanics (any race).

Colon and Rectum Cancer Comparison of Remaining Life Cancer Risk, 2015–2017

Source: SEER*Explorer. Incidence data from SEER 21 areas; mortality data from National Center for Health Statistics.[4]

Colorectal Cancer, Around the World

So, we’ve seen that it’s difficult to draw conclusions using only overall incidence and mortality trends, even within a single country, but what can we say about the disease on an even larger scale, around the world? Unsurprisingly, this is even more complicated. “There is a large geographic difference in the global distribution”—countries with the highest rates have up to 10 times greater incidence than countries with the lowest rates—and these differences have changed significantly over time:[6]

In parts of Northern and Western Europe, the incidence of colorectal cancer may be stabilizing, and possibly declining gradually in the United States. Elsewhere, however, the incidence is increasing rapidly, particularly in countries with a high-income economy that have recently made the transition from a relatively low-income economy, such as Japan, Singapore, and Eastern European countries. Incidence rates have at least doubled in many of these countries since the mid-1970s.

What have been the most significant changes in countries with transitioning economies? For one thing, they have adopted a more typical “Western” lifestyle. With that lifestyle, they have also adopted Western risk factors, including critical dietary risk factors such as the high consumption of animal foods and the low consumption of fibrous whole plant foods.[5]

As rapidly increasing populations in Africa and some parts of Asia follow in the footsteps of Japan, Singapore, and Eastern European countries, how will we cope with the ballooning global burden of this disease and other diseases like it? Many of these countries, including India, currently have very low incidence and mortality rates, but huge populations that are rapidly changing their dietary lifestyles. According to recent rates, even young Americans (under 50) are much more likely to develop colorectal cancer[4] than Indians of all ages,[5] but that will not last long.

Are we ready for these shifts to occur? Are we doing enough to prevent them?

What Victory Against Colorectal Cancer Really Looks Like: Getting Back to Our Roots

There has been a lot of research on the risk factors associated with colorectal cancer incidence and mortality, and none stands out more than diet. For colon cancer specifically, it is conservatively estimated that, “healthful diet and lifestyle factors” could reduce 70% of the cancer burden; these factors should not be viewed as an “isolated goal, but as part of an overall dietary and lifestyle strategy to optimize health and well-being.”[7] It turns out—as you might expect!—what’s good for reducing the risk of colorectal cancer is also good for reducing the risk of other chronic diseases.

And what is that dietary advice? It’s simple. Avoid diets high in fat, especially animal fat; avoid high meat consumption as a general rule; especially avoid meats cooked at high temperatures, which results, “in the production of heterocyclic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.”[6] Also, consume more fruits and vegetables, especially high-fiber fruits and vegetables, which “dilute fecal content, increase fecal bulk, and reduce transit time.”[6]

In other words, advice you’ve heard before: Eat your veggies! While we shouldn’t forget about other lifestyle factors associated with colorectal cancer—physical inactivity, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption[6]—starting with dietary change is a great way to stave off not only this major killer but also many of the other top causes of death. What’s to lose?

What Can We Learn From the Example of Colorectal Cancer?

In the greater context of the “war on cancer,” colorectal cancer seems a clear success. Compared to other cancer sites, incidence and mortality rates for colorectal cancer have improved tremendously. And there’s a chance that we would know much less about this disease, including how to prevent and treat it, if not for the concerted efforts of recent decades.

Still, these encouraging trends should be interpreted with a degree of caution. Whether or not we interpret recent decades’ efforts as successful will depend on numerous other factors, especially age, sex, race, and geographic location. And all of these factors are further complicated when we look at global trends.

It’s fair to celebrate the advancements, but also to point out the many opportunities for continued growth. US incidence and mortality rates still rank highly compared to much of the world. Knowing that diet and other lifestyle choices play such a large role, there’s no reason we can’t reduce incidence and mortality rates far more than we already have, at least as low as the rates seen in south-central Asia and most of Africa. Should we increase our focus on these lifestyle factors, we will begin to see a much more impressive victory against cancer.

This article is part of a series on The Future of Nutrition: An Insider’s Look at the Science, Why We Keep Getting It Wrong, and How to Start Getting It Right by T. Colin Campbell, Ph.D., (with Nelson Disla).

References

- American Cancer Society. What is Colorectal Cancer? (2020) Online access: December 4, 2020. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/about/what-is-colorectal-cancer.html

- AAmerican Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2019. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2019/cancer-facts-and-figures-2019.pdf

- Mayo Clinic. Colon Cancer (2019). Online access: December 4, 2020. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/colon-cancer/symptoms-causes/syc-20353669

- National Cancer Institute (NCI) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER). SEER*Explorer (2020). https://seer.cancer.gov/explorer/application.html?site=1&data_type=1&graph_type=2&compareBy=sex&chk_sex_3=3&chk_sex_2=2&race=1&age_range=1&hdn_stage=101&rate_type=2&advopt_precision=1&advopt_display=2

- Rawla, P., Sunkara, T., Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Przeglad gastroenterologiczny 14(2), 89–103 (2020). https://doi.org/10.5114/pg.2018.81072

- Hagga, F. A., & Boushey, R. P. Colorectal cancer epidemiology: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery 22(4), 191–197 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1242458

- Willett, W. C. Diet and Cancer. JAMA 293(2), 233–234 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.2.233

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits