This could be a wake-up call. A shocking lead article in The New York Times reports that Vitamin E, long considered a miracle nutrient by many, is linked to illness and death.[1] I can only wonder how this “breaking news” will be broadcast and remembered, especially by those who only read headlines.

In recent decades, vitamin E has been one of the trendiest of all nutrients. Many people know that there is evidence showing that it associates with less heart disease and cancer, slower aging, less skin blemishes, and numerous other benefits. Biochemically, these effects are often explained by vitamin E’s ability to neutralize highly oxidizing free radicals. In the marketplace, it is widely used in skin care products and is a popular nutrient supplement.

Such has been the enthusiasm for this nutrient. I still remember when a group of prominent researchers were first reporting that vitamin E consumption is associated with lower heart disease 30 years ago. The finding was so impressive that everyone in the research group began taking vitamin E supplements. To some extent, vitamin E became a buzzword. It was, perhaps, the antidote for heart disease.

“For the first time, we have detected a potential toxin of concern, vitamin E acetate, from biological samples… taken from the lungs of 29 [vaping] patients, including two who died.”

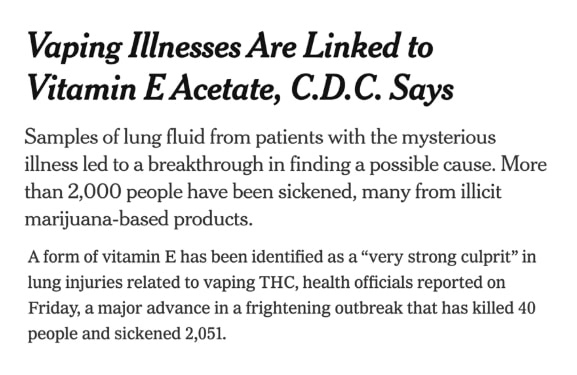

But, now this: “For the first time, we have detected a potential toxin of concern, vitamin E acetate, from biological samples… taken from the lungs of 29 [vaping] patients, including two who died.” According to Dr. Anne Schuchat of the CDC, these samples “provided evidence of vitamin E acetate at the primary site of injury in the lungs.” Whoa! Because this news was a top story in The New York Times, among other high-profile media, I assume that the journalist, too, must have considered it very significant. Granted, the illness and death of vaping patients is significant in its own right, but I believe this story was especially incendiary and deserves added attention due to the involvement of vitamin E.

Before going further, however, I need to add a word of caution. That is, I do not infer, especially without evidence, that all health products containing vitamin E acetate are toxic. In fact, I am reasonably confident that conventional products do not pose harm. Though the evidence is not sufficient, I might even hypothesize that the body might be concentrating extra vitamin E at the primary site of injury in order to help control the damage, similar to white blood cells being recruited to fight foreign infectious agents of disease. This may be a bit far-fetched, but without further evidence, so could other possible inferences of this report be far-fetched.

But still playing it safe, we cannot rule out the possibility that vitamin E acetate may be toxic under some conditions. Vitamin E acetate is an unnatural form of vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol). I know little or nothing about vaping products except that they are a popular source of cannabis (THC), but I have questions. Why is this revered vitamin added to a product for which there is widespread concern about its safety? Did they suspect that it might minimize risk of vaping? Not according to the CDC. “Vitamin E acetate is sticky, like honey and clings to lung tissue,” and according to the news account, it is used to dilute the THC and increase profits. However, does vitamin E acetate specifically cause or contribute to the toxicity? One might wonder whether the addition of vitamin E acetate to these products is approved. The answer is no: the FDA has no jurisdiction over the regulation and use of these products. Regulation tends to be more of an individual state mandate. As an aside, President Trump, acting at a federal level, might be exempting vape shops from restrictions because, according to this same news account, “the industry had created a lot of jobs.” I wonder. Is this what this is about—job creation? If the motivation for adding vitamin E acetate was purely financial, why did manufacturers not use a cheaper diluting agent with a similar consistency? Might the health appeal of vitamin E have played into this decision?

But these speculations are not the main reason I write this article. Rather, I do so to show an example of a story that trades on the word “nutrition,” intentionally or unintentionally. Stories like this have the potential to add more confusion to this already-confusing science. When nutrition comes up for discussion, it mostly focuses on individual nutrients—food contents, nutrient effects both good and bad, amounts needed on a daily basis—as if this represents most of nutrition. It is my contention, as I explain in my forthcoming book, that this overwhelming focus on individual nutrients is counterproductive. The confusion surrounding “nutrition” is made worse still by the focus given to nutrients in various synthetic forms and used out of context. The concept of nutrition, as it currently exists requires a major overhaul at its most fundamental level.

In this particular case, I can only wonder whether manufacturers are indeed adding a popular nutrient to these vaping products—presumably with the goal of making these products more acceptable (safer?) and profitable? Did manufacturers choose this product because it is a well-known antioxidant known for intercepting harm? It turns out harm is the product, as told by the news account.

If you allow me to continue this speculation, manufacturers are skipping over several important steps. Vitamin E acetate is not the natural form of vitamin E found in food, it is being inhaled instead of being consumed and digested and it is being used in isolation, without companion nutrients in food that ensure its proper digestion, absorption, and metabolism in the body. Is anyone equating this form and use of vitamin E with vitamin E consumed in food?

What I find troubling with this story is that it further worsens our misunderstanding of the concept of nutrition, which goes back more than a century. The history of nutrition going back to at least the 1800s, considered in my upcoming book, demonstrates the urgent need to unlearn some of our most deeply established beliefs and practices in this science.

Moreover, I submit that our detail-oriented approach to nutrition is not only confusing but also demonstrably harmful. We speak of a nutrient as a fixed chemical structure without knowing that there may be multiple structures (isomers) and metabolites thereof, fixed reactions causing fixed responses, fixed activities acting within fixed environments, fixed rates of transport, and fixed relationships with other nutrients and non-nutrients. In this approach to nutrition, we are far more smitten with an illusion of isolation than a fact of interconnection. This approach has paralyzed progress in so many areas of our society. Yet, in my decades of experience, I have often heard expressions of well intended scientists that this approach of specificity and relative certainty, even without connectedness, is defined as the best of science. Despite the interconnection seen throughout nature, we humans go about our business—and it is a profitable business model—disconnecting all things natural.

The “nutrition” that we subscribe to— and that which is perceived by contemporary science—is excellent for the accumulation of wealth for the few, not health for the many. In the example told here, “nutrition” may be providing vaping manufacturers with a neat marketing tool. And if the effects of this “nutrition” are not what we desire, no worry: we will produce new remedies for solving any unwelcome effects.

Sadly, we’ve lost something—the idea that nutrition is an expression of Nature. Is it possible that we might check in on Madame Nature to ask how she creates health and wealth for all, simultaneously? Something that we can never fully duplicate, no matter how stubbornly we try?

References

- Tibbles, W. The Protein Requirement; or, “Do We Eat Too Much Meat?”. British medical journal 2, 1349-1351 (1911).

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits