In our article on the cost of malnutrition, we saw that chronic diseases linked to malnutrition are bankrupting both individuals and society while inflicting a heavy yet preventable death toll.

Unsurprisingly, these runaway health care costs are the frequent focus of many public, professional, and political debates. What is surprising are the things we don’t hear about in those debates. Namely, we don’t hear about permanently reducing costs and preventing deaths by addressing the root causes of most chronic diseases; very rarely do we hear anything about the lifestyle factors that promote disease. Instead, the constant focus is on how we might distribute the costs, the role (if any) of private health insurance, access to care, negotiating with drug companies, and other issues. Of course, those are important discussions, but they miss out on our profound ability to reduce and control disease risk.

If ours were a functional system that prioritized health care, many of the challenges associated with the cost of health care would immediately improve. In such a functional system, nutrition would be a top priority and the burden of related diseases would be substantially lessened. Instead, we have a disease response system characterized by 1) heavy reliance on pharmaceutical technology and 2) reactivity rather than proactivity.

Technology in the Disease Response System

The pharmaceutical protocol, in particular—the creation of drugs—is a patently (and heavily patented) technological strategy. It targets predetermined challenges (e.g., how can we manage high cholesterol or hypertension) by manufacturing precise solutions, regardless of where those challenges come from or what side effects might result. Patients are assigned one pill for a particular ailment, possibly another to deal with the side effects of the first, a third to deal with a separate issue not targeted by either of the first two, and on and on, eventually resulting in what is commonly referred to as a drug cocktail or polypharmacy.[1]

In one description of a new model developed by the Weizmann Institute of Science for comparing drug combinations, “the fine art of mixing drug cocktails is incredibly complicated” but offers great promise for “personalized medicine.”[2] The article goes on to discuss “optimal blends [. . .] even when a large number of ingredients is called for.”

No matter how fanciful the language of “personalized medicine” may be, the goal of that medicine is the same as for any other example of traditional pharmacotherapy: it responds to disease by applying a technological understanding of the human body. It does so while adding a seemingly sophisticated twist—it says that your type II diabetes is different from my type II diabetes, much less my coronary heart disease. Why? Because each of us is dealing with a distinct genetic profile, either innate or adapted, our drug cocktails must be optimally designed to fit our particular needs. Just as you would not repair an electric vehicle by retrofitting it with a turbo-charged eight-cylinder engine, you would not treat Alzheimer’s disease with chemotherapy agents meant for cancer (and for good reason—cognitive impairment is one of the commonly reported side effects that results from chemotherapy).[3]

But what if we aren’t cars after all? What if the food we eat every day (or don’t eat every day) could prevent and reverse heart disease?[4]–[7] What if numerous large-scale population studies established associations between the food we eat, cancer, and other diseases?[8]–[14] What if numerous experimental animal studies shed light on the many mechanisms by which those associations operate?[15]–[25] If there existed broad agreement, even in the nutrition-negligent medical community, that other costly diseases could be prevented and even treated by nutrition—what then? Would it still make sense to emphasize technological solutions above all else?

A recent survey indicates that the disease response system’s reliance on technology is only growing.[26] It cites an 85 percent increase in total prescriptions filled for American adults from 1997 to 2016. We have reached a moment when most American adults (55 percent of those surveyed) regularly use prescription drugs.

If this approach was only ineffective, it would be a cause for concern. However, the truth is even worse: it is often downright dangerous. According to the same survey, “More than a third of [those taking prescription drugs] say no provider has reviewed their medicines to see if all are necessary,” increasing the risk of adverse effects. According to Donald Light, PhD, at the Safra Center for Ethics at Harvard, “the FDA does not acknowledge” the fact that prescription drugs are “a major health risk” and the fourth leading cause of death, killing more than 100,000 Americans every year.[27] (Other estimates have indicated this may be as high as 440,000 deaths per year.) He goes on to say that for every adverse drug reaction that results in hospitalization, 29 more cases of adverse drug reactions occur.

If you think this pattern will be easy to overcome, consider this: the revenue from the global pharmaceutical market in 2023 ($1.6 trillion) exceeds the gross national income (GNI) of most economies worldwide, including the GNI of Spain, Indonesia, and Argentina.[28][29] The sad fact is that the current approach is not only often ineffective and hazardous but also tremendously profitable and therefore difficult to challenge.

Make no mistake—a high-functioning health care system will rightly include technology. Technology often serves a critical role. But in the case of chronic diseases like heart disease, we would do well to consider the alternatives. These diseases are caused more than anything else by unnatural diets. To treat them by technology alone, without addressing those diets, is no way to emphasize health care. It also puts professionals in the unenviable position of always playing catch-up.

Reactive Disease Care

In addition to its technocentric character, the disease response system is almost entirely reactive, not proactive. As we have just described, pills and procedures are not suited to preventing the conditions that give rise to disease.

The same can be said for medical specialization in general: by focusing on ever-more-distinct categories of disease and disease response, the system’s specialized health professionals are less prepared to understand, much less to address, the systemic conditions underlying disease. Each professional is increasingly focused on responding to disease outcomes affecting their particular part of the human machine rather than preventing disease from entering the entire system.

This is not a critique of medical professionals as individuals but of the system that limits them. If anything, those professionals should be among the strongest advocates for a new approach to health care. The current system puts many of them in the impossible position of promoting health well past the point of disease’s takeover. They are the face of health care, asked to intervene when called on, but are limited in their ability to proactively establish the conditions supporting true health.

Their disease response system puts them at a great disadvantage. And for what? How effective is this disease response system anyway? In part two, we will look closely at trends in how our society’s health has changed with the current system.

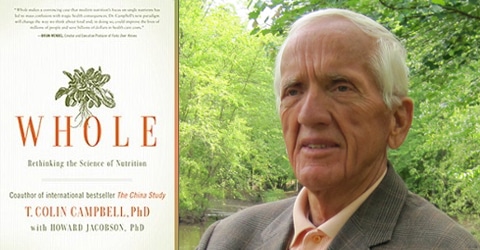

This article is part of a series on The Future of Nutrition: An Insider’s Look at the Science, Why We Keep Getting It Wrong, and How to Start Getting It Right by T. Colin Campbell, PhD, (with Nelson Disla) released December 2020.

References

- Weymann, D. K., Smolina, E. J., Gladstone, and Morgan, S. G. High-Cost Users of Prescription Drugs: A Population-Based Analysis from British Columbia, Canada. Health Serv Res 52, no. 2 697-719 (2017). http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12492

- Weizmann Institute of Science. How to mix the perfect (drug) cocktail. ScienceDaily (2016). http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/12/161208121908.htm

- Raffa, R.B. Cancer ‘survivor-care’: II. Disruption of prefrontal brain activation top-down control of working memory capacity as possible mechanism for chemo-fog/brain (chemotherapy-associated cognitive impairment). J Clin Pharm Ther 38(4), 265-268 (2013). doi:10.1111/jcpt.12071

- Ornish, D., Brown, S. E., Scherwitz, L. W., Billings, J. H., Armstrong, W. T., Ports, T. A. et al. Can lifestyle changes reverse coronary heart disease? Lancet 336, 129–133 (1990).

- Esselstyn, C. B., Jr. Updating a 12-year experience with arrest and reversal therapy for coronary heart disease (an overdue requiem for palliative cardiology). Am. J. Cardiol. 84, 339–341 (1999).

- Esselstyn, C. B. Jr., Ellis, S. G., Medendorp, S. V., & Crowe, T. D. A strategy to arrest and reverse coronary artery disease: a 5-year longitudinal study of a single physician’s practice. J. Family Practice 41, 560–568 (1995).

- Esselstyn, C. B. Jr., Gendy, G., Doyle, J., Golubic, M., & Roizen, M. F. A way to reverse CAD? J Fam. Pract. 63, 356–364b (2014).

- Carroll, K. K., Braden, L. M., Bell, J. A., & Kalamegham, R. Fat and cancer. Cancer 58, 1818–1825 (1986).

- Ganmaa, D. & Sato, A. The possible role of female sex hormones in milk from pregnant cows in the development of breast, ovarian and corpus uteri cancers. Med Hypotheses 65, 1028–1037 (2005). doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2005.06.026

- Armstrong, D. & Doll, R. Environmental factors and cancer incidence and mortality in different countries, with special reference to dietary practices. Int. J. Cancer 15, 617–631 (1975).

- Connor, W. E. & Connor, S. L. The key role of nutritional factors in the prevention of coronary heart disease. Prev Med 1, 49–83 (1972).

- Jolliffe, N. & Archer, M. Statistical associations between international coronary heart disease death rates and certain environmental factors. J. Chronic Dis. 9, 636–652 (1959).

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, nutrition, physical activity, and prevention of cancer: a global perspective. American Institute for Cancer Research (2007).

- Hildenbrand, G. L. G., Hildenbrand, L. C., Bradford, K., & Cavin, S. W. Five-year survival rates of melanoma patients treated by diet therapy after the manner of Gerson: a retrospective review. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 1, 29–37 (1995).

- Madhavan, T. V. & Gopalan, C. The effect of dietary protein on carcinogenesis of aflatoxin. Arch. Path. 85, 133–137 (1968).

- Schulsinger, D. A., Root, M. M., & Campbell, T. C. Effect of dietary protein quality on development of aflatoxin B1-induced hepatic preneoplastic lesions. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 81, 1241–1245 (1989).

- Youngman, L. D. & Campbell, T. C. Inhibition of aflatoxin B1-induced gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase positive (GGT+) hepatic preneoplastic foci and tumors by low protein diets: evidence that altered GGT+ foci indicate neoplastic potential. Carcinogenesis 13, 1607–1613 (1992).

- Gurtoo, H. L. & Campbell, T. C. A kinetic approach to a study of the induction of rat liver microsomal hydroxylase after pretreatment with 3,4-benzpyrene and aflatoxin B1. Biochem. Pharmacol. 19, 1729–1735 (1970).

- Nerurkar, L. S., Hayes, J. R., & Campbell, T. C. The reconstitution of hepatic microsomal mixed function oxidase activity with fractions derived from weanling rats fed different levels of protein. Journal of Nutrition 108, 678–686 (1978).

- Preston, R. S., Hayes, J. R., & Campbell, T. C. The effect of protein deficiency on the in vivo binding of aflatoxin B1to rat liver macromolecules. Life Sci. 19, 1191–1198 (1976).

- Prince, L. O. & Campbell, T. C. Effects of sex difference and dietary protein level on the binding of aflatoxin B1 to rat liver chromatin proteins in vivo. Cancer Res. 42, 5053–5059 (1982).

- Krieger, E. Increased voluntary exercise by Fisher 344 rats fed low protein diets (undergraduate thesis). Cornell University (1988).

- Krieger, E., Youngman, L. D., & Campbell, T. C. The modulation of aflatoxin (AFB1) induced preneoplastic lesions by dietary protein and voluntary exercise in Fischer 344 rats. FASEB J. 2, 3304 Abs. (1988).

- Horio, F., Youngman, L. D., Bell, R. C., & Campbell, T. C. Thermogenesis, low-protein diets, and decreased development of AFB1-induced preneoplastic foci in rat liver. Nutrition and Cancer 16, 31–41 (1991).

- Youngman, L. D., Park, J. Y., & Ames, B. N. Protein oxidation associated with aging is reduced by dietary restriction of protein or calories. Proc. National Acad. Sci 89, 9112–9116 (1992).

- Preidt, R. Americans taking more prescription drugs than ever. WebMD (2017). https://www.webmd.com/drug-medication/news/20170803/americans-taking-more-prescription-drugs-than-ever-survey.

- Light, D. W. New prescription drugs: a major health risk with few offsetting advantages. Safra Center for Ethics (2014). https://ethics.harvard.edu/blog/new-prescription-drugs-major-health-risk-few-offsetting-advantages.

- Mikulic, M. Global pharmaceutical industry—statistics and facts. Statista (2019). https://www.statista.com/topics/1764/global-pharmaceutical-industry/.

- Wikipedia. List of countries by government budget. Wikipedia (2019). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_government_budget.

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits