In Part 1, we saw that the disease response system is characterized by a heavy reliance on technology (especially pharmaceutical advances) and reactivity (as opposed to proactivity). Although that article included a few startling figures on the deaths and accidents caused by prescription drugs, a more general question remains: How effective is the disease response system as a whole? And how do we measure its effectiveness?

Life Expectancy: An Incomplete Measure

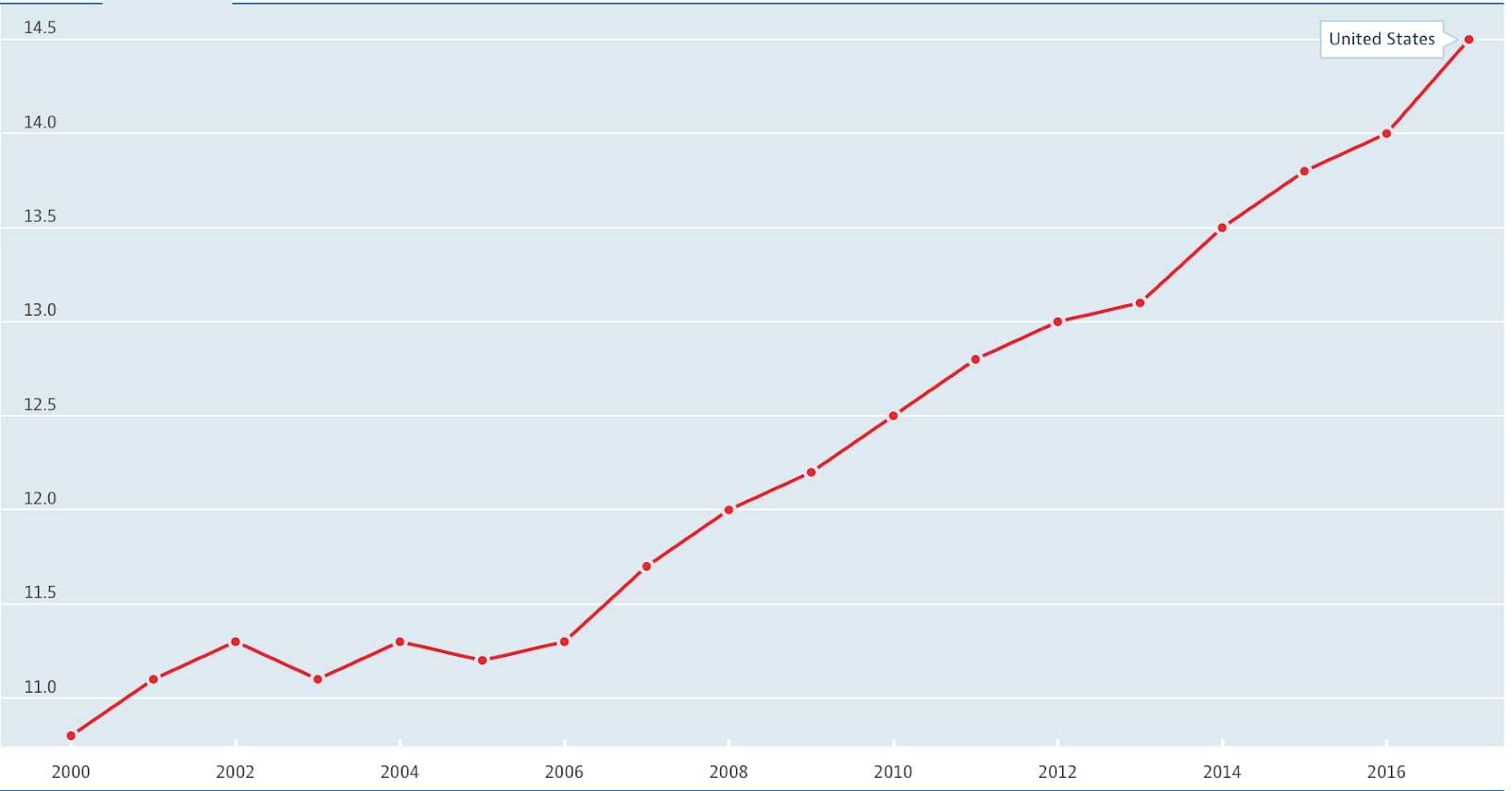

Many public and professional commentators use life expectancy to assess the healthcare system’s effectiveness. This is a limited indicator of overall health. It’s important to live a life that is not only long but also healthy, so we should not take life expectancy as the be-all and end-all. Nevertheless, life expectancy trends can be useful. Here’s what those trends show in the US:[1]

- From 1960 to 2014, life expectancy increased from 71 to more than 78 years, at about two months per year.

- In 2015, life expectancy increased by only 1.2 months.

- From 2016 to 2018, life expectancy decreased from 78.8 to 78.6 years. This is the longest decline since the Spanish flu and World War I (1915–1918).[2]

Life expectancy at birth: US and other G7 countries (Japan, Italy, France, Canada, United Kingdom, Germany), 1960–2017

Source: OECD (2020), Life expectancy at birth (indicator).

doi: 10.1787/27e0fc9d-en (Accessed on 04 September 2020)

This decline has been widely discussed, for good reason. It is a cause for serious concern. The prevailing wisdom attributes much of the decline to increasing overdose and suicide rates.[3][4] But the story is more complicated than that. Many factors contribute to overdose and suicide rates, and it can be difficult to parse them. As mentioned in a previous article on the costs of malnutrition, so-called deaths of despair[5] do not exist in a vacuum. To get a fuller picture, we must look beneath our despair and understand how we suffer individually, communally, and societally. Part of that process is admitting the role of factors like malnutrition, chronic disease, and the general failings of our costly disease-response system.[6][7]

Suicides per 100 000, 2000–2017

Source: OECD (2020), Suicide rates (indicator).

doi: 10.1787/a82f3459-en (Accessed on 04 September 2020)

Still, the overall life expectancy trends outlined above don’t seem that bad. After all, life expectancy did increase steadily until 2015. This is a welcome trend, right? We must be healthier overall if we are living longer—or so the thinking goes.

It turns out that much of the increases in life expectancy are due to improved strategies for responding to disease, especially emergencies. Improved rapid response to heart disease in particular has resulted in fewer years lost prematurely.[8]

Advances in how the medical system responds, especially to acute illness and emergency, obviously deserve recognition, but let’s be clear—they do not prove that our overall health has improved. These trends suggest that the disease-response system has improved its methods of responding to disease.

Disease Incidence

Perhaps a better indicator of health, or a lack of health, is trends in the incidence (number of new cases) of our greatest killers. These tell us whether we are doing well to prevent disease in the first place.

Looking at those incidences,[9] we see somewhat of a mixed bag:

- The incidence of heart disease and stroke have remained relatively stable in recent decades.

- The incidence of diabetes—the most expensive chronic disease in America,[10] costing $327 billion per year[11]—has increased dramatically: “Age-adjusted incidence rates of diabetes doubled between 1980 and 2008 for both men and women between the ages of 18 and 79,” and the age-adjusted death rate for diabetes also increased by nearly fifty percent;

- Except for a couple cancers, including cancers of the lung/bronchus and of the larynx (the incidences of which have decreased due to reduced cigarette smoking), there has been little favorable change in cancer incidence rates in recent decades; the incidence of certain cancers has even increased.

This final example, cancer, illustrates the point about living with disease (i.e., responding to disease after it has developed) without preventing or treating disease. The result of this combination is that there is a more substantial proportion of cancer patients living in our society today. While this is obviously preferable to the alternative of cancer patients dying at a higher rate, it gives you an idea of how healthcare spending has increased to such an unsustainable extent.

Takeaways

Undoubtedly, improved disease response is a worthy goal. In emergency cases, improved disease response is often the difference between life and death. We should never deprioritize that response. But when it comes to diseases that can also be prevented and treated, the relative ineffectiveness of our prevention and treatment does begin to stand out.

The comparison of lung cancer illustrates this point quite well. We have been successful in decreasing the incidence of lung cancer, but why? Is lung cancer really that much easier to prevent than diabetes, which has moved in the opposite direction? Are we dealing with these two diseases differently? If so, why? If they are both preventable, why is the messaging from authoritative health policy institutions so different? If taking a stand against smoking has proven effective, then why have we not yet taken a stand against the standard American diet? (Incidentally, fifty years ago, it was shown that a healthful diet can also reduce lung cancer deaths, especially among heavy smokers.)[12]

The National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion has a page dedicated to the health and economic costs of chronic diseases[13] While it mentions cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption, it does not mention diet. I wonder at all the reasons why—at all the industries that profit from the food you eat and the management of the resultant diseases, at the limited strategies by which we respond to those diseases—and I wonder what the incidence trends of diabetes and other diseases related to malnutrition might look like if our society treated the consumption of provably dangerous foods the same as it treats the inhalation of provably dangerous tar and nicotine.

This article is part of a series on The Future of Nutrition: An Insider’s Look at the Science, Why We Keep Getting It Wrong, and How to Start Getting It Right, the latest book by T. Colin Campbell, PhD (with Nelson Disla). Learn more about the book here.

Read more articles in the “Future of Nutrition” series from Dr. T. Colin Campbell and Nelson Disla:

Healthcare vs Disease Response System – Part 1

Is it Time to Quit the “War on Cancer”?

How Much Does Malnutrition Really Cost?

References

- Hanowell, B. Life expectancy is, overall, increasing. SlateGroup (2016). https://slate.com/technology/2016/12/life-expectancy-is-still-increasing.html.

- Solly, M. U.S. life expectancy drops for third year in a row, reflecting rising drug overdoses, suicides. Smart News(2018). https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/us-life-expectancy-drops-third-year-row-reflecting-rising-drug-overdose-suicide-rates-180970942/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Increase in suicide mortality in the united states, 1999–2018 (2020). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db362.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). NCHS data on drug-poisoning deaths (2018). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/factsheets/factsheet-drug-poisoning.htm

- Case A. & Deaton A. Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism. Princeton University Press (2020).

- Goodwin, G. M. Depression and associated physical diseases and symptoms. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience 8(2), 259–265 (2006).

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Opioid overdose crisis (2020). https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/opioids/opioid-overdose-crisis

- Beltran-Sanchez, H., Preston, S. H., & Canudas-Romo, V. An integrated approach to cause-of-death analysis: cause-deleted life tables and decompositions of life expectancy. Demogr Res 19, 1323 (2008). doi:10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.35

- Crimmins, E. M. & Beltran-Sanchez, H. Mortality and morbidity trends: is there compression of morbidity? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 66, 75–86 (2011) doi:10.1093/geronb/gbq088

- American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS). American diabetes association report: diabetes is the most expensive chronic disease in america. Connect (2018). https://connect.asmbs.org/07-2018/american-diabetes-association-report-diabetes-is-the-most-expensive-chronic-disease-in-america

- American Diabetes Association. Economic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2017. Diabetes Care 41(5): 917–928 (2018). https://doi.org/10.2337/dci18-0007

- Shekelle, R. B. & Raynor W. J. Jr. Dietary Vitamin a and Risk of Cancer in the Western Electric Study. Lancet 2: 1185-90 (1981).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP). Health and economic costs of chronic diseases (2020). https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/costs/index.htm

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits