-

“Evidence that disputes the status quo will always be controversial, whether it is true or not, because that’s the very definition of controversy: disagreement over conventional understanding… To downplay scientific evidence because it is controversial is to downplay scientific evidence for the very same, fundamental reason that science is celebrated.” T. Colin Campbell, Introduction to The Future of Nutrition

At the end of November 2023, Stanford nutrition researchers including Christopher Gardner, PhD, published the findings of a new twin study in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA).[1] Six weeks later, a four-part documentary series about the study, You Are What You Eat: A Twin Experiment, debuted on Netflix.[2] Given the attention garnered by the study and miniseries, I decided to dig into the research, digesting not only the JAMA paper but also the paper’s lengthy supplements, which offer much greater detail on the study design and include all the data published to date.

The eight-week clinical study is, in many respects, a perfect natural experiment. Researchers randomly assigned half of each identical twin pair to a “healthy vegan diet” and the other half to a “healthy omnivorous diet,” thus automatically eliminating the confounding influences of age, sex, and genetic factors on clinical outcomes and allowing the differential impact of the two diets to be measured. Differences in clinical outcomes were found as early as four weeks into the study. By the end of the eight-week study, researchers found that the twins consuming a “healthy vegan diet showed significantly improved low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentration, fasting insulin level, and weight loss compared with twins consuming a healthy omnivorous diet.”

The authors conclude their paper by summarizing their observations and offering a somewhat timid recommendation for clinicians: “In this randomized clinical trial, we observed cardiometabolic advantages for the healthy vegan vs. the healthy omnivorous diet among healthy, adult identical twins. Clinicians may consider recommending plant-based diets to reduce cardiometabolic risk factors, as well as aligning with environmental benefits.” Those who haven’t read the study could be forgiven for concluding that the main message is that people just need to eat more plants, as opposed to also eliminating animal products. In an interview to publicize the study’s findings for Stanford Medicine News, Gardner stated, “What’s more important than going strictly vegan is including more plant-based foods into your diet.”[3]

I can only speculate as to why Gardner framed the study’s conclusion in this watered-down fashion. Perhaps he wanted to appeal to the large majority of the public that would reflexively dismiss the idea of switching to a 100 percent plant-based diet. Perhaps he was also cognizant that his increasing visibility, as a result of the Netflix documentary, could make him a target for the ire of authorities in the food industry, especially if he were to draw attention to the negative impact of overconsumption of animal protein on cardiometabolic health, let alone recommend the elimination of meat and dairy products from the nation’s diet.

Below, I argue that based on the study’s data such wishy-washy framing of the results is misleading. While the results do indeed support the adoption of a plant-based diet, the limited advice to include more plant-based foods in your diet does a disservice to the public by neglecting to publicize the most obvious contributor to the beneficial impact observed for the vegan group compared to the omnivorous group: the absence of animal products.

Study Background

The starting point for this twin study is the recognition that “Abundant evidence from observational and intervention studies[4][5][6][7][8][9][10] indicates that vegan diets are associated with improved cardiovascular health and decreased cardiovascular disease, likely because of the higher consumption of vegetables and fruits, legumes, whole grains, and nuts and seeds compared with other different types of dietary patterns.[11]” We can see from this framing that already the researchers have in mind that the increase in plant-based foods is the primary factor in promoting cardiovascular health. There is no mention whatsoever of animal protein. The authors then point out that most of the studies looking into the health benefits of vegan diets have been epidemiological rather than clinical, and they express concern about confounding variables in epidemiological studies. Specifically, they note the “bias of self-decided vegans who may differ from nonvegans in factors that may influence diet and health.” This is a reasonable concern for epidemiological studies conducted in the US and other highly industrialized countries. However, it suggests that the researchers are either unaware of the China Study or do not believe its findings are relevant. Since the China Study was conducted in rural China at a time when diets in any given village were remarkably homogeneous, even as they differed from those in other villages, the confounding effect described was irrelevant. Peasants in any given village did not “self-decide” between meat-heavy and vegan diets. They had no choice in the matter. Dr. Campbell was able to compare health outcomes across more than a hundred villages that differed in their typical diet, especially in the continuous variable of the proportion of calories coming from animal protein.

Study Design

The Stanford study was innovative in that it compared 22 pairs of identical adult twins assessed to be healthy at the outset of the study (based on widely accepted markers of cardiovascular health such as BMI, LDL cholesterol, and blood pressure) and randomized to follow either a “healthy vegan diet” or a “healthy omnivorous diet,” both of which were designed to be “replete with vegetables, legumes, fruits and whole grains and void of sugars and refined starches.” The researchers told the participants in both groups to eat until they were satiated. No effort was made to make the two diets isocaloric (i.e., of equal total energy), so calorie intake was not controlled for.

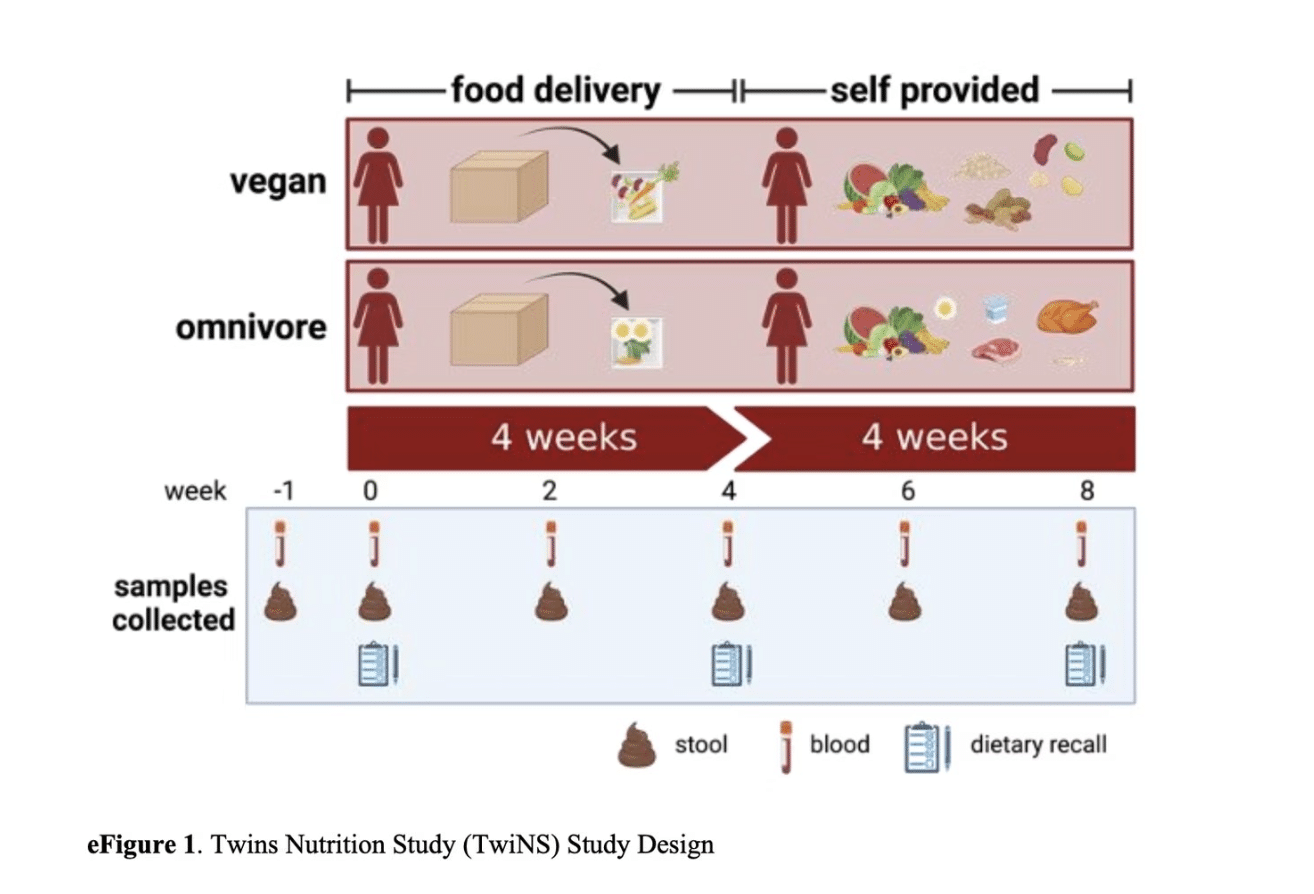

Body measurements and lab tests were completed at baseline, four weeks, and eight weeks. Stool samples were also collected at regular intervals for future analysis. For the first four weeks, all meals were provided by a meal service called Trifecta Nutrition. During this initial period, the study subjects also received health educator counseling on how to shop for and prepare meals that adhered to the criteria for the recommended healthy diet. In the second four weeks, they shopped for and made their own meals and had access to health educator support. Participants were asked to log their food intake using the Cronometer app. The food log data was shared in real time with health educators, allowing them to proactively reach out to participants to help them course correct and stick to the guidelines.

The graphic below, shown as it appears in supplement 2, illustrates the study design.

Study Outcomes

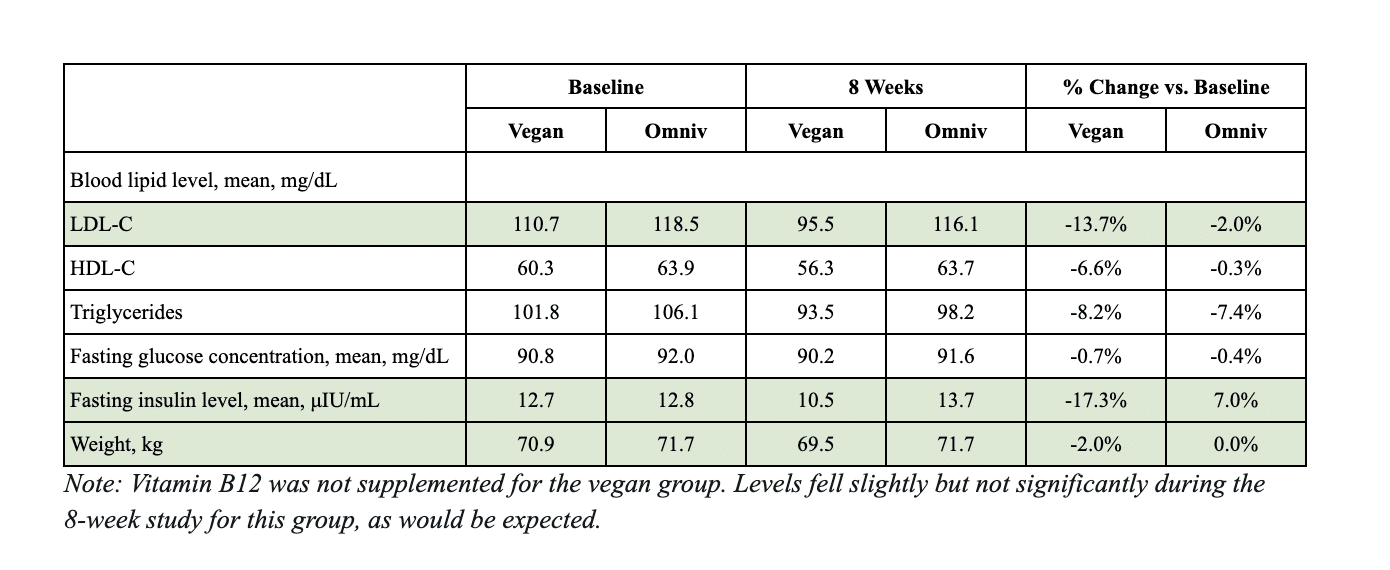

At eight weeks, the vegan group had significantly improved LDL-C, fasting insulin level, and weight loss relative to the omnivorous group. The differences are especially impressive given the short length of the study and the fact that the baseline values of these measures were considered normal. The table below shows the week eight data compared to baseline values. The metrics highlighted by the study authors are shaded green.

Why Did the Vegan Group Do Better?

Despite the significant differences in key measures of cardiovascular and metabolic health between the participant groups at the eight-week mark, the JAMA paper does not take a strong position on this question. The researchers state, “Although our findings suggest that vegan diets offer a protective cardiometabolic advantage compared with a healthy, omnivorous diet, excluding all meats and/or dairy products may not be necessary because research[12][13] suggests that cardiovascular benefits can be achieved with modest reductions in animal foods and increases in healthy plant-based foods compared with typical diets.”

To answer the question, I delved deep into supplement 2 (linked to the main paper) and focused on two things:

- What exactly were participants told to eat to be compliant with their specific diet?

- How closely did participants adhere to that guidance? (i.e., what did they actually eat?)

Dietary Guidance

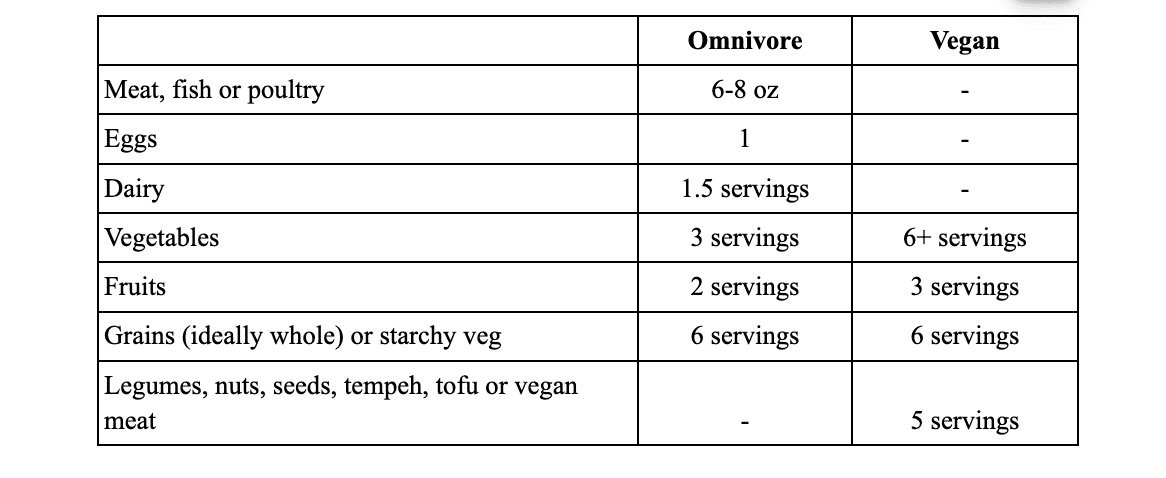

Health educators gave detailed instructions to each group, including specific targets for the number of daily servings of different kinds of foods:

- The healthy omnivorous diet group was told to eat enough animal products daily to differentiate from the vegan group. Specifically, this included targets of six to eight ounces of meat, fish, or poultry, one egg, and one and a half servings of dairy each day, on average. Aside from animal products, targets included three servings of vegetables, two servings of fruit, and six servings of grains or starchy vegetables each day.

- The healthy vegan diet group was told to avoid all animal products for the course of the study. Specific targets included six or more servings of vegetables, three servings of fruit, five servings of legumes, nuts, seeds, or vegan meat, and six servings of grains or starchy vegetables each day.

For ease of comparison, these guidelines are summarized in the table below. No restrictions were imposed on the use of salt or fatty plant foods, including oils. No supplements were provided.

Additionally, to ensure that both groups of participants would consume diets “healthier compared to their pre-study dietary pattern demonstrated by increased vegetable intake and decreased refined grains intake [emphasis added],” health educators instructed all study participants to:

- Choose minimally processed foods.

- Build a balanced plate with vegetables, starch, protein, and healthy fats.

- Choose variety within each food group.

- Individualize these guidelines to meet preferences and needs.

How closely did participants adhere to the guidance for their specific diet?

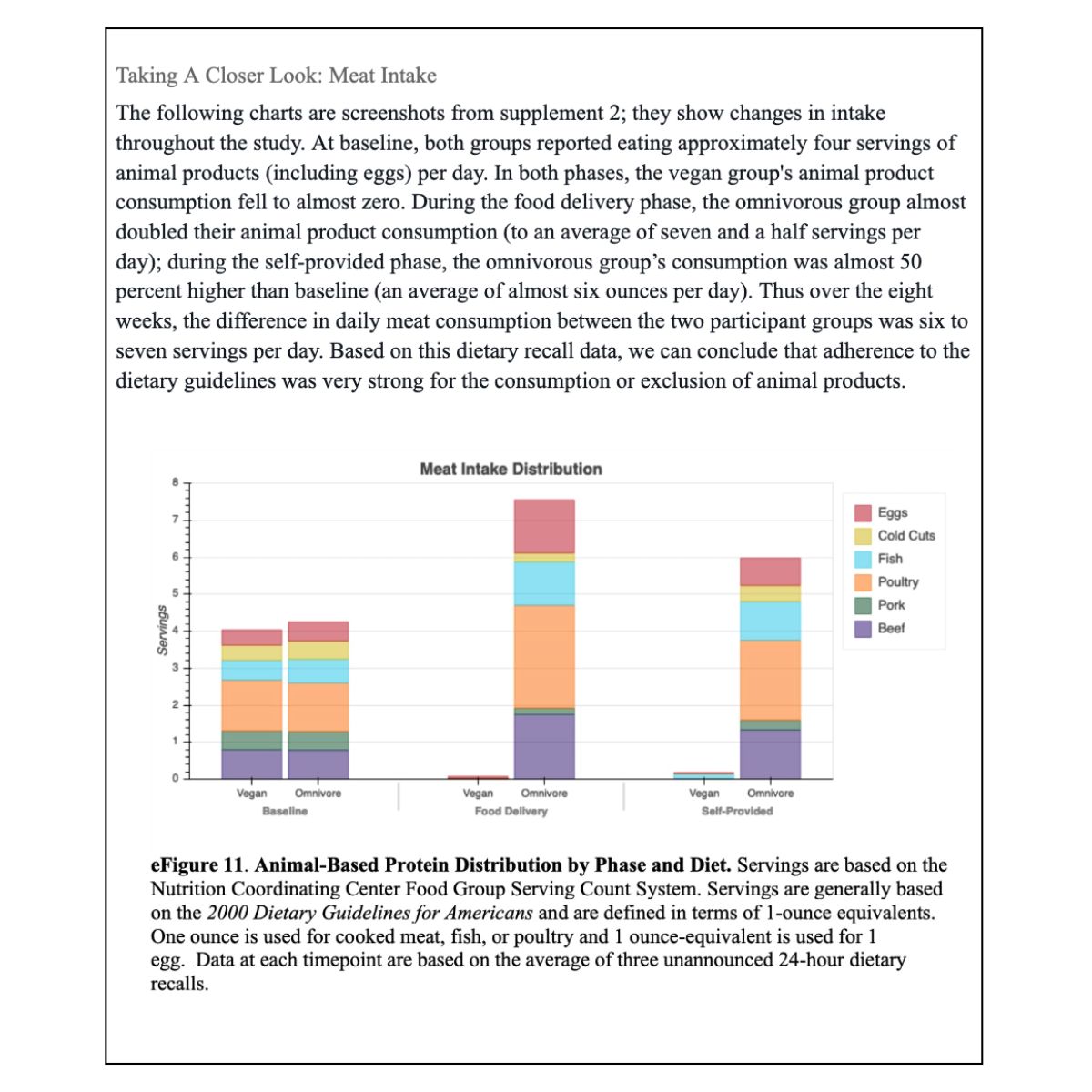

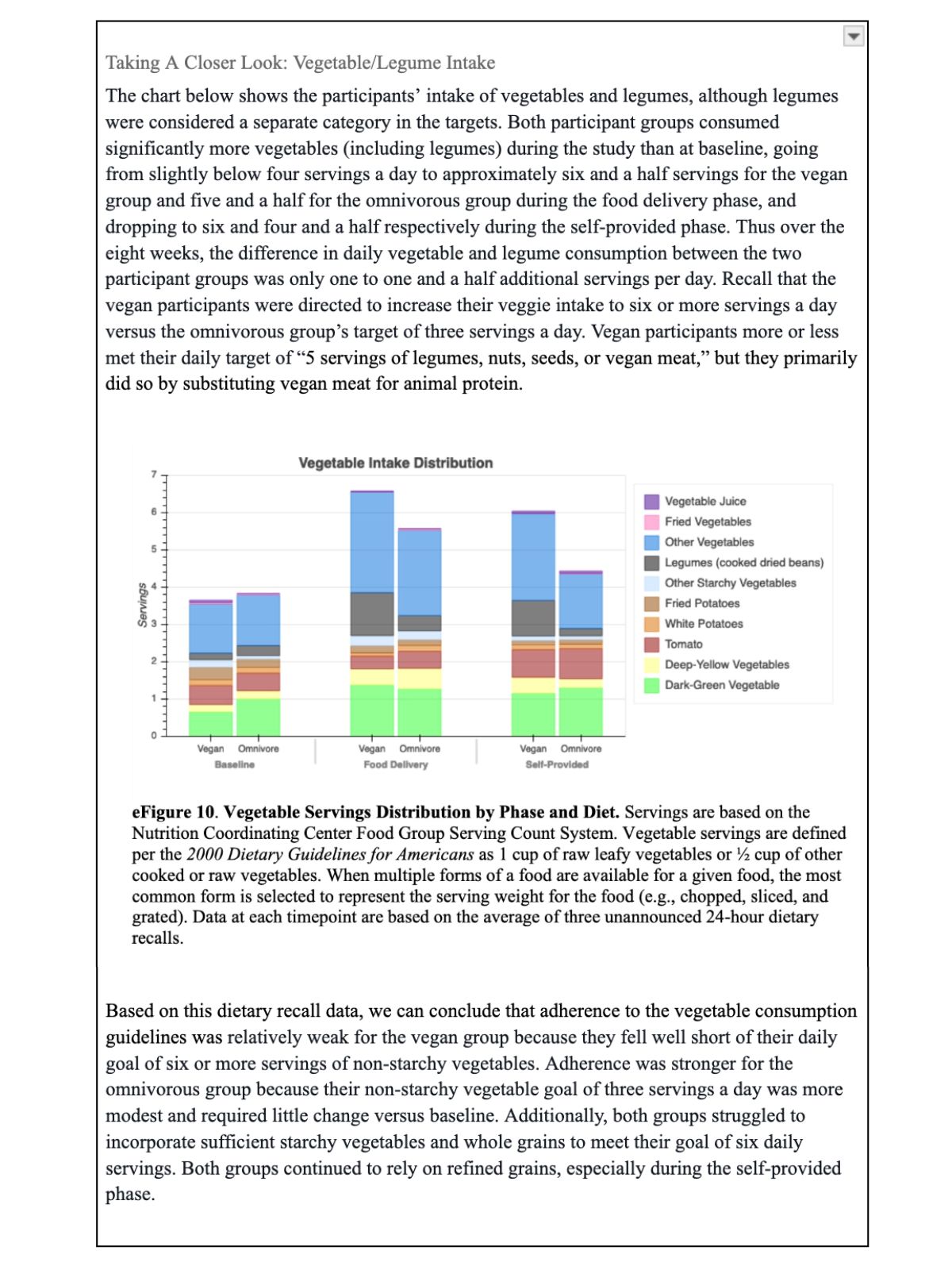

Supplement 2 provides summaries of self-reported food intake at baseline, following the food delivery phase (week four), and following the self-provided phase (week eight). These data were gathered via unannounced 24-hour dietary recall interviews with participants which were conducted three times during week zero (baseline), three times during week four, and three times during week eight.

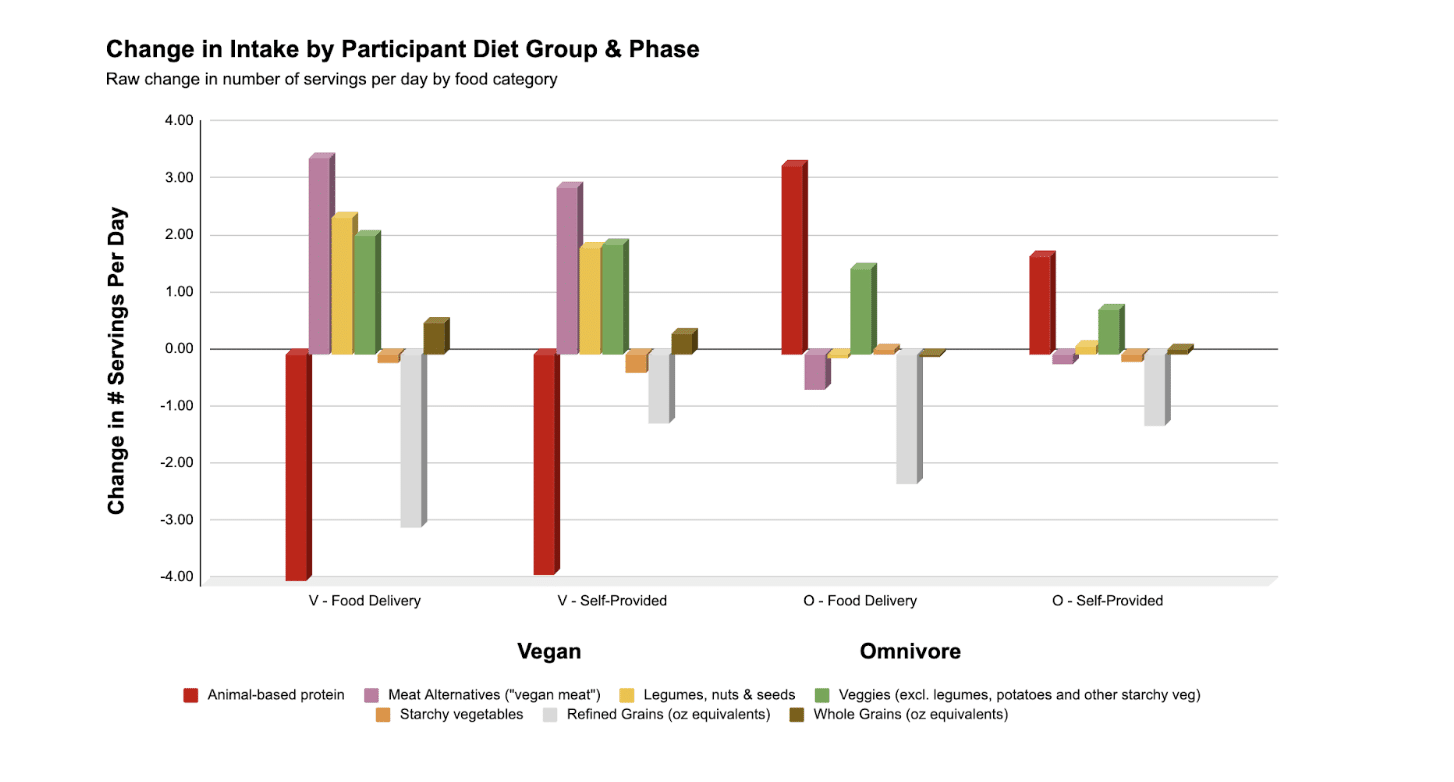

The chart below shows the change in the average number of servings per day of different food groups compared to the baseline intake.

It is immediately apparent that for both vegan and omnivorous groups the increase in the number of servings of non-starchy vegetables (green bar) is modest relative to changes in the principal source of protein; i.e., animal versus plant protein. The omnivorous group ate more meat each day than at baseline while the vegans ate none. Meanwhile, the increase in veggie servings for vegans is not much greater than the increase for omnivores. Starchy vegetable intake actually fell for the vegan group and barely moved for the omnivorous group. The chart also illustrates that while both groups of participants decreased their intake of refined grains, they barely increased their consumption of whole grains.

In summary, adherence to the specific dietary targets was strongest for the consumption or exclusion of animal products. It is harder to assess how well participants followed the general dietary guidance, such as ensuring variety and balance across food groups. What we do know is that the vegan group primarily substituted animal products with meat alternatives (vegan meat). Since most of these are highly processed, it seems likely that their diet was relatively heavy in ultra-processed food, despite the direction to choose minimally processed foods.

A Missed Opportunity

A mere glance at the data in supplement 2 reveals that both the recommendations and the actual diet consumed by the vegan group during the eight weeks fall way short of a whole food, plant-based (WFPB) diet. The vegan diet’s positive impact on cardiovascular and metabolic health, while statistically significant, was likely less impressive than what could have been achieved within the eight-week time frame with a vegan diet that more closely resembled a WFPB diet.

As Dr. Campbell writes in The Future of Nutrition, the WFPB diet can be described in a dozen words, distilled to two recommendations:[14]

- Consume a variety of whole, plant-based foods.

- Avoid consumption of animal-based foods.

Despite claims to the contrary, the researchers created a vegan diet that, when implemented, was largely defined by what it eliminated rather than what it emphasized. While the vegan participants did indeed avoid almost all animal protein—all meat, dairy, and eggs—they were not advised to consume only whole plants. Their diets were intended to be “minimally processed,” but they were not told to exclude oils or meat alternatives which tend to be highly processed and laden with oil. The fact that vegan participants relied heavily on vegan meat during the food delivery phase and the self-provided phase suggests that this was a design choice, not a bug. On the plus side, participants were told to “choose variety within each food group.” Had they met the targets for vegetables and chosen whole grains instead of refined grains, their diets would have aligned more closely to optimal.

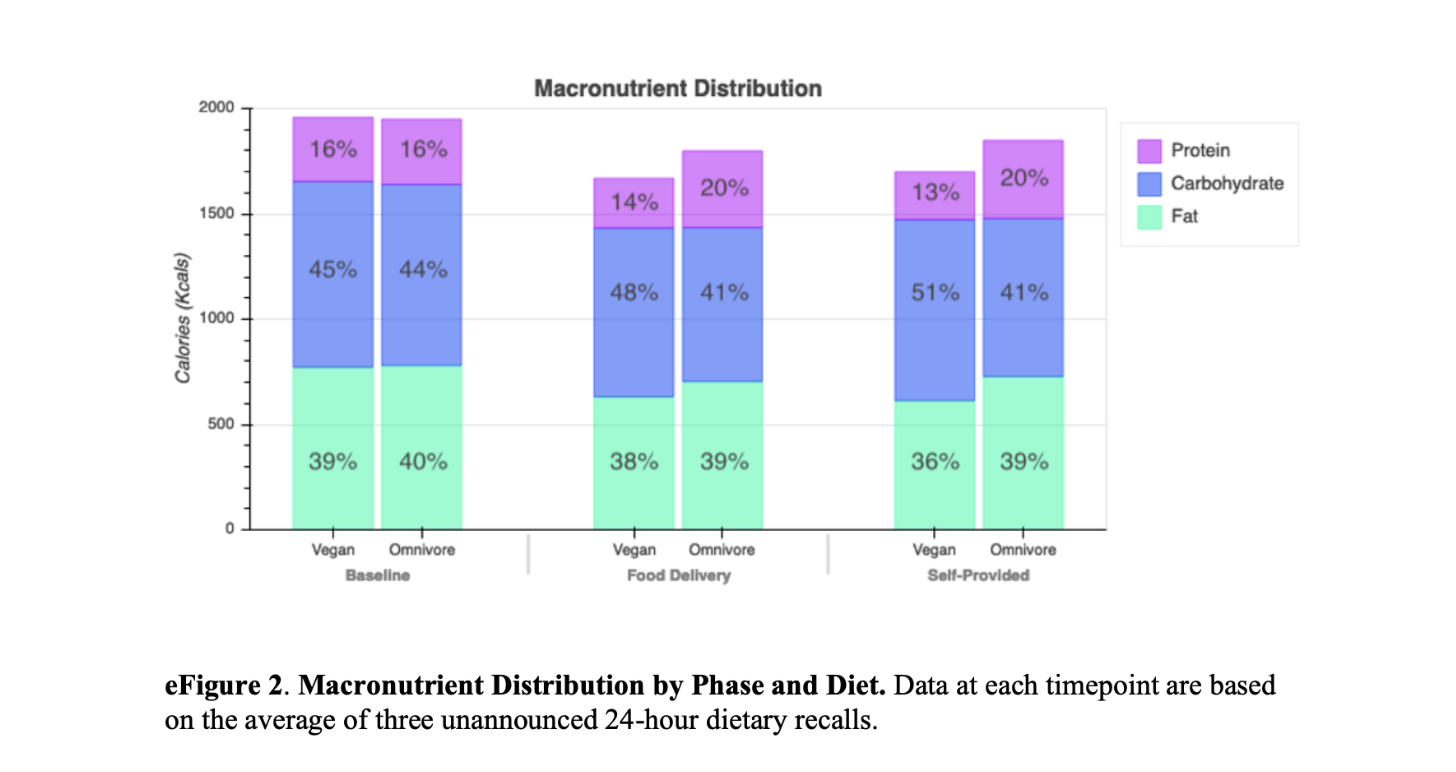

The macronutrient distribution chart below, pulled from supplement 2, shows that fat intake for the vegan group never dipped below 36 percent of total calories, as compared to CNS’s recommendation of 10 percent, the average proportion of calories that fat comprises in whole plants. Protein intake fell to 13–14 percent, which is slightly higher than CNS’s recommendation, while carbohydrate intake increased only slightly from 45 to 48 percent during the food delivery phase and up to 51 percent during the self-provided phase. Carbohydrate intake thus fell well below the 70–80 percent that CNS recommends.

Since we know that the researchers worked with Trifecta to “develop menu offerings to match a healthy vegan and omnivorous diet, which emphasized vegetables, fruits, and whole grains while limiting added sugars and refined grains,” it seems reasonable to assume that the diet the vegan participants consumed during the first four weeks closely matched the intent of the researchers. That said, to “meet their energy requirements,” participants were allowed to purchase and consume snacks in addition to their three provided meals, so we cannot know for sure.

The Bottom Line: Unfulfilled Potential

The Stanford Twin Nutrition Study (TwiNS) is garnering a great deal of attention and helping to shift the Overton Window on what counts as acceptable knowledge in nutrition. Still, I cannot help but be disappointed that the researchers held back from articulating the clear findings related to animal protein. Buried in supplement 2, there is an acknowledgment that “Vegan participants’ intake of protein overwhelmingly came from plant-based sources, while the majority of omnivorous participants’ intake of protein came from animal-based sources [emphasis added].” But there is no discussion of the importance of this stark difference in the diets and no acknowledgment of the relatively modest difference in vegetable consumption.

The unfulfilled potential of the study is very common in dietary studies and appears to reflect low expectations around participants’ ability to make radical changes to their diets. (To learn more about the difficulties of trying to achieve optimal health with only moderate changes, read about the dietary pleasure trap.)

As Dr. Campbell writes in The Future of Nutrition, there are many examples of how “the scientific community selectively prohibits certain ‘controversial’ subjects (when they threaten the status quo) from discussion.” Until leading researchers like Gardner (who has been mostly vegan for decades) are willing to be more direct about the consequential impact of animal products, especially animal protein, on cardiovascular and metabolic health, we are not going to meaningfully shift the discourse.

Having said that, I do look forward to additional papers based on this study. The paper notes, “Stool samples were collected for future analysis to examine changes to the gut microbiome, metabolites, inflammatory markers, and additional health factors.” Such studies would be fascinating given that even identical twins typically have meaningful differences in their microbiome. Hopefully, more analysis will be released over time, including on the levels of dietary adherence and the relative impact of animal product consumption versus plant intake on microbiome health.

References

- Landry MJ, Ward CP, Cunanan KM, et al. Cardiometabolic Effects of Omnivorous vs Vegan Diets in Identical Twins: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(11):e2344457. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.44457

- Psihoyos L, dir. You Are What You Eat: A Twin Experiment. Released January 1, 2024, on Netflix.

- Moskal E. Twin research indicates that a vegan diet improves cardiovascular health. Stanford Medicine News. November 20, 2023. https://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2023/11/twin-diet-vegan-cardiovascular.html

- Kaiser J, van Daalen KR, Thayyil A, Cocco MTARR, Caputo D, Oliver-Williams C. A systematic review of the association between vegan diets and risk of cardiovascular disease. J Nutr. 2021;151(6):1539-1552. doi:10.1093/jn/nxab037

- Dybvik JS, Svendsen M, Aune D. Vegetarian and vegan diets and the risk of cardiovascular disease, ischemic heart disease and stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Nutr. 2023;62(1):51-69. doi:10.1007/s00394-022-02942-8

- Selinger E, Neuenschwander M, Koller A, et al. Evidence of a vegan diet for health benefits and risks – an umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational and clinical studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. Published online May 16, 2022. doi:10.1080/10408398.2022.2075311

- Satija A, Hu FB. Plant-based diets and cardiovascular health. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2018;28(7):437-441. doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2018.02.004

- Gardner CD, Vadiveloo MK, Petersen KS, et al; American Heart Association Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health. Popular dietary patterns: alignment with American Heart Association 2021 dietary guidance: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023;147(22):1715-1730. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001146

- Thompson AS, Tresserra-Rimbau A, Karavasiloglou N, et al. Association of healthful plant-based diet adherence with risk of mortality and major chronic diseases among adults in the UK. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(3):e234714. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.4714

- Turner-McGrievy GM, Barnard ND, Scialli AR. A two-year randomized weight loss trial comparing a vegan diet to a more moderate low-fat diet. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15(9):2276-2281. doi:10.1038/oby.2007.270

- Parker HW, Vadiveloo MK. Diet quality of vegetarian diets compared with nonvegetarian diets: a systematic review. Nutr Rev. 2019;77(3):144-160. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuy067

- Satija A, Bhupathiraju SN, Spiegelman D, et al. Healthful and unhealthful plant-based diets and the risk of coronary heart disease in US adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(4):411-422. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.047

- Fleming JA, Kris-Etherton PM, Petersen KS, Baer DJ. Effect of varying quantities of lean beef as part of a Mediterranean-style dietary pattern on lipids and lipoproteins: a randomized crossover controlled feeding trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;113(5):1126-1136. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqaa375

- Campbell TC. The Future of Nutrition (with Nelson Disla). BenBella Books, Inc., Dallas TX, 2020.

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits