Just before 2020 closed out, the 164-page 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGAs) were released by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).[1] The purpose of these guidelines, released every five years, is to provide, “advice on what to eat and drink to meet nutrient needs, promote health, and prevent disease”.[2]

And while most Americans rarely give a thought to the the DGAs when shopping for food or cooking dinner, these guidelines play a critical role in determining which foods are prioritized in all national food programs, including school breakfast and lunch programs and food assistance programs, which provide food for over 70 million Americans a year.[3-5] Understanding how those guidelines are created is therefore critical to understanding how American nutrition policy works (or, as the case may be, fails).

Who Creates the DGAs?

Before the USDA and HHS finalize the DGAs, the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee—made up of twenty nutrition and medicine experts—meet to review the latest studies on nutrition and health. This past July, they released The Committee’s Scientific Report summarizing their findings.[6] The USDA and HHS, guided by that report, then create the final DGAs for the public; simply put, top health scientists make evidence-based recommendations to inform how our government gives nutrition advice to Americans.[7] Sounds simple enough, right?

Source: Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025

Unfortunately, not so much. By the time the final DGAs are released, there are often large discrepancies between the Advisory report and the guidelines that determine national food programs, and these discrepancies have seriously negative impacts on our health. Here are the big three from the 2020–2025 DGAs:

1. Added Sugar

Advisory Committee Recommendation: ≤ 6% of daily calories from added sugar.

Final Dietary Guidelines Recommendations: ≤ 10% of daily calories from added sugar.

The Committee’s Scientific Report echoed what nutrition science has been screaming for decades: higher intake of added sugars, particularly from sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) are associated with type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality.[8-11] For that reason, the Committee recommended reducing added sugars to ≤6% of total calories. This recommendation is in line with a broader recommendation that Americans consume at least 85% of total calories from nutrient-dense foods, leaving no more than 15% for added sugars and saturated fat.

And yet the DGAs recommended limited added sugars to ≤10% of total daily calories.

Both the Advisory Committee’s and DGA’s recommendations rested on two major assumptions: (1) that Americans are consuming only the most nutrient-dense versions of foods to meet recommendations (i.e., Steel-cut oatmeal vs. sweetened breakfast cereal to meet grains recommendations), and (2) that Americans are not consuming alcohol, another low-nutrient calorie-dense beverage. Unfortunately, neither of these assumptions are true. In fact, 56% of adults over 21 years-old reported consuming alcohol in the past month, and nearly half of those currently drinking reported binge drinking.[12] Thus, to keep within recommended calorie intake while still meeting nutrient-dense food recommendations, one would have to balance and reduce added sugar intake to accommodate for saturated fat and alcohol.

2. Alcohol

Advisory Committee Recommendation: ≤1 drink per day for both men and women.

Final Dietary Guidelines Recommendations: ≤2 drinks per day for men and ≤1 drink a day for women.

The Advisory Committee outlined a large body of evidence showing that alcohol does not improve human health and that both higher consumption levels and binge drinking are associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality. Ethanol, the chemical compound itself, has no nutritional value, and alcoholic beverages provide few recommended food groups or nutrients. While the DGAs do advise that those not currently drinking do not start, they still allow for up to 2 drinks a day for men and 1 drink a day for women. The differences in recommendations between genders stem from general differences in body mass and alcohol’s impacts on different body masses. However, the Advisory Committee argued that substantial evidence shows that men who drank 2 drinks a day had “modest but meaningful increase in [mortality] risk” compared to men who drank 1 drink a day.

3. Saturated Fat

Advisory Committee Recommendation: Reduce saturated fat intake and replace with unsaturated fat.[6]

Final Dietary Guidelines Recommendations: Limit saturated fat intake to ≤10% daily calories.

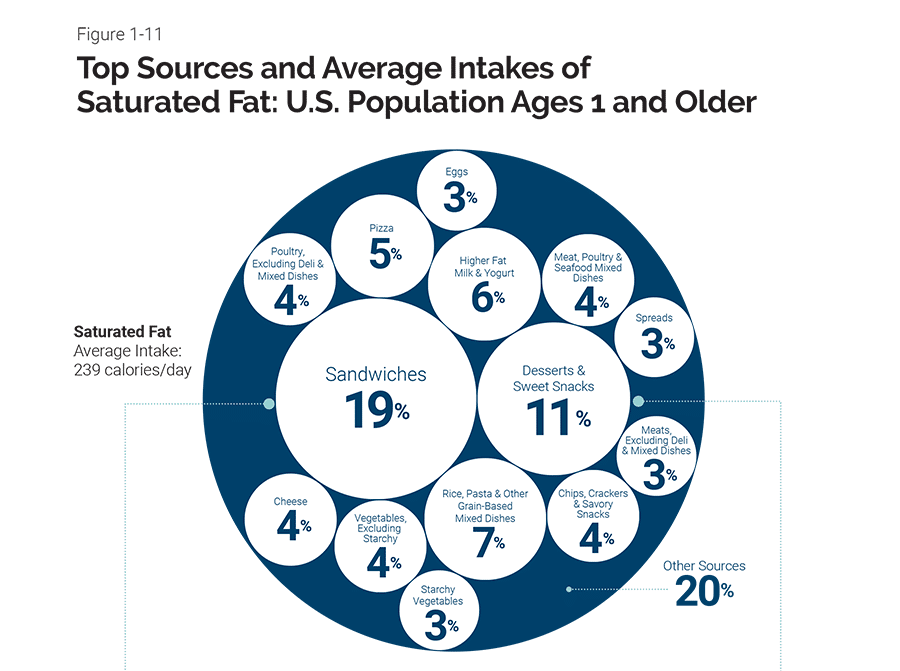

The Advisory Committee outlines strong evidence that diets lower in saturated fat are associated with lower LDL and total cholesterol in children, and that substituting saturated with unsaturated fat was associated with lower risk of heart disease and cardiovascular disease mortality in adults.[6] But while the Committee Report defined “fatty meats and full-fat cheese” as major sources of saturated fat[6], the final DGAs state that the largest sources of saturated fat are “sandwiches, including burgers, tacos, and burritos; desserts and sweet snacks; and rice, pasta, and other grain-based mixed dishes.”[2] This statement bypasses the true culprits of saturated fat in our diet: meat, eggs, high-fat dairy products and refined plant oils.

The Advisory Committee is explicit that not all substitutions are equal. Replacing saturated fat with refined carbohydrates does not improve, and can even worsen, CVD risk; on the other hand, substituting saturated fat with unsaturated fat, found mainly in whole plant foods, can lower CVD risk.[13] However, the DGAs recommendation for lowering saturated fat intake is that Americans choose low-fat dairy or leaner cuts of meat.[2] But does this recommendation go far enough to encourage optimal health? Given that the average adult is not meeting recommended vegetable intakes, particularly dark-green vegetables and legumes,[2] why not recommend foods like soy milk, collard greens, and beans over dairy and lean meat?

Why Do We See These Differences?

While we’d like to think the United States government hands off our national nutrition guidelines to the best and most informed scientists, the Advisory Committee’s job is severely limited: they can only advise the DGAs. They may not always go far enough in their recommendations, but even if they do, there is no guarantee that those recommendations will be heeded. Those responsible for final DGAs can veto, revise, and ignore any recommendations from the Committee’s report. And unlike the Committee, the two individuals who oversee the DGAs are not nutrition researchers or physicians. They are politically appointed cabinet members—in this case, Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue and Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar.[14,15] Perdue, the former governor of Georgia, violated the law by advocating for President Trump’s reelection in 2020.[16] Alex Azar is a former executive of Eli Lily, a pharmaceutical company based in Indianapolis.[17] In addition to lacking any authority or expertise in nutrition, can we really trust that these two appointees have the American peoples’ best interests in mind?

Or are they merely puppets of our administration’s agenda and of corporate dominance over the American food system?

References

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 9th ed. U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2020.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Purpose of the Dietary Guidelines | Dietary Guidelines for Americans. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/about-dietary-guidelines/purpose-dietary-guidelines. Published 2020. Accessed January 9, 2021.

- Food and Nutrition Services. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation and Costs. U.S. Department of Agriculture; 2020.

- Food and Nutrition Services. WIC Program Participation and Costs. U.S. Department of Agriculture; 2020. https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/wic-program . Accessed September 29, 2020.

- Food and Nutrition Services. National School Lunch Program: Participation and Lunches Served. U.S. Department of Agriculture; 2020. https://www.fns.usda.gov/nslp. Accessed September 29, 2020.

- Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Scientif Ic Report of the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service; 2020.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Who’s Involved in Updating the Dietary Guidelines. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/about-dietary-guidelines/process. Published 2020. Accessed January 10, 2021.

- Evert AB, Dennison M, Gardner CD, et al. Nutrition therapy for adults with diabetes or prediabetes: A consensus report. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(5):731-754. doi:10.2337/dci19-0014

- Rahman I, Wolk A, Larsson SC. The relationship between sweetened beverage consumption and risk of heart failure in men. Heart. 2015;101(24):1961-1965. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307542

- Lee AK, Binongo JNG, Chowdhury R, et al. Consumption of less than 10% of total energy from added sugars is associated with increasing HDL in females during adolescence: a longitudinal analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(1):e000615. doi:10.1161/JAHA.113.000615

- Collin LJ, Judd S, Safford M, Vaccarino V, Welsh JA. Association of sugary beverage consumption with mortality risk in US adults: A secondary analysis of data from the REGARDS study. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e193121. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3121

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Rockville, Maryland: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2017.

- Sacks FM, Lichtenstein AH, Wu JHY, et al. Dietary fats and cardiovascular disease: A presidential advisory from the american heart association. Circulation. 2017;136(3):e1-e23. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000510

- Bluestein G. Donald Trump picks Sonny Perdue as secretary of agriculture. Atlanta. News. Now. https://www.ajc.com/news/state–regional-govt–politics/breaking-donald-trump-taps-sonny-perdue-his-agriculture-chief/oWpJvzgWCungyRdmw0N8FP/. Published August 10, 2017. Accessed January 11, 2021.

- Mangan D. Senate confirms Alex Azar as President DonaldTrump’s health chief. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2018/01/24/senate-confirms-alex-azar-as-president-donaldtrumps-health-chief.html. Published January 24, 2018. Accessed January 11, 2021.

- The Associated Press. USDA head Perdue violated Hatch Act by advocating for Trump re-election, gov’t watchdog says. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2020-election/usda-head-perdue-violated-hatch-act-advocating-trump-re-election-n1242687. Published October 9, 2020. Accessed January 11, 2021.

- Cancryn A, Karlin-Smith S. Trump picks ex-pharma executive Azar to lead HHS . Politico. https://www.politico.com/story/2017/11/13/alex-azar-hhs-secretary-trump-244837. Published November 13, 2017. Accessed January 11, 2021.

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits