You may be familiar with the term autoimmune given the popular media’s increasing attention to chronic inflammation and autoimmune disease. Autoimmune means that the body has an immune reaction to substances naturally present in the body. In other words, the immune system attacks the self. This can happen in most parts of the body; accordingly, more than eighty autoimmune diseases have been named and described. Many autoimmune diseases are rare and not very extensively researched. Table 1 lists a few of the more common examples.

Table 1. Small sample of autoimmune diseases (out of >80)

| thyroid | Hashimoto thyroiditis Graves disease |

| joints/skin | psoriasis vitiligo rheumatoid arthritis ankylosing spondylitis |

| central nervous system | multiple sclerosis |

| pancreas | type 1 diabetes |

| gastrointestinal tract | Crohn’s disease ulcerative colitis celiac disease |

Though many individual conditions are very rare, autoimmune diseases are collectively quite common, affecting about 7–10 percent of the population, with women being more commonly afflicted.[1] These diseases can be extremely difficult to diagnose and often present with vague symptoms like fatigue, odd pains, or skin rashes. Given the prevalence, the lack of scientific understanding, and the vague symptoms, autoimmune diseases have become something of a catch-all in the public mind. (And it seems that the prevalence of autoimmune disease is increasing.)[2] If an illness goes undiagnosed and is composed of a collection of nonspecific symptoms, many people are quick to wonder whether an autoimmune disease might be the cause.

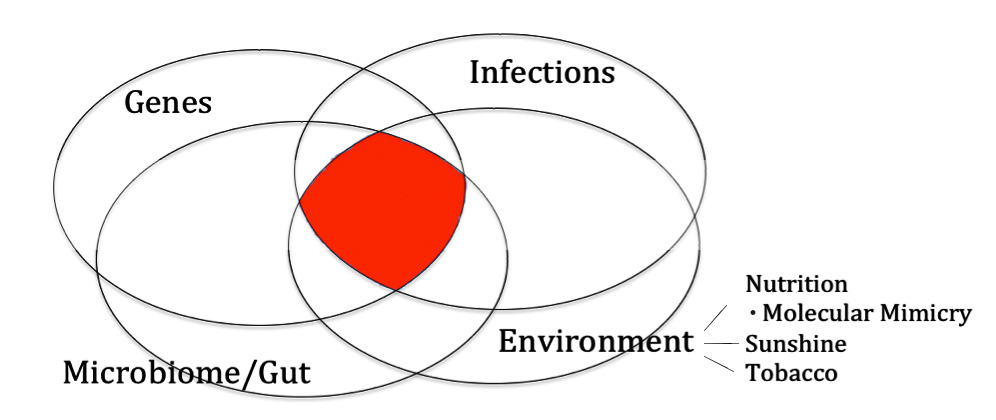

Autoimmune disease is complicated—extraordinarily complicated. According to my reading of the literature, several intertwined factors may affect risk:

- genes

- infections

- environment (including diet, sun exposure, and tobacco use)

- gut health (including the bacteria living in your intestine and their activity)

Let’s go through each of these briefly to illustrate their importance.

Genes

I have known many patients, particularly patients with family members who were afflicted, who believed autoimmune disease is nearly 100 percent genetic. It turns out that genes matter a great deal for some autoimmune diseases but are less important for others.

It seems that whenever more genetic research is done for any one disease, more regions of our genes are found to be involved in risk.[3] Human leukocyte antigens (HLA genes) are particularly prominent in autoimmune disease as they are involved in the body being able to distinguish the self from foreign invaders. For example, all celiac patients have one of two HLA genes, though many other genes may be involved.[4]

Table 2 shows summary data from identical twin studies.[5] Identical twins are useful to study because they have exactly the same genes. The term concordance in this context refers to the probability that a twin will have a disease given that their twin also has the disease.

Table 2. Autoimmune concordance among identical twins

| Disease | Concordance |

|---|---|

| type 1 diabetes | 13-47% |

| multiple sclerosis | 0-50% |

| celiac disease | 60-75% |

| autoimmune thyroid disease | 17-22% |

| psoriasis | 35-64% |

| Crohn’s disease | 20-50% |

| ulcerative colitis | 6-18% |

| lupus | 11-40% |

| rheumatoid arthritis | 0-21% |

| ankylosing spondylitis | 50-75% |

Some conditions, like celiac disease and ankylosing spondylitis, seem to have very strong genetic components. But the risk of getting many other autoimmune conditions, like multiple sclerosis, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, and type 1 diabetes, is clearly affected by something other than genes.

In other words, for many of these autoimmune conditions, having high-risk genes may be a necessary but not sufficient reason for a person to get the disease. It’s something more than just genes.

Infections

Certain infections are linked to autoimmune diseases. This should come as no surprise. Consider what your body does in response to infections: it revs up the immune system to fight the invaders.

In some cases, infections may actually lower the risk of autoimmune disease; in other cases, they may cause autoimmune disease.[6] How could they be protective? One theory is that growing up in a more and more sterile environment, increasingly common in modern life, is not good for the immune system. In simplistic terms, it’s almost as if the immune system needs some practice to get it right. In experiments involving mice bred to have a high risk of developing type 1 diabetes, researchers can prevent the disease by exposing the mice to infections early in life.[6]

Infections can be damaging too. Several autoimmune diseases have been linked to specific infections. Sometimes, it seems that chronic infection and inflammation from a viral or bacterial invader can precipitate immune system confusion at some point, triggering the start of the autoimmune process.[6] People who have been exposed to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which causes mono, have a higher rate of multiple sclerosis.[7][8] Those infected with EBV in adolescence or later in life have a 30 times higher risk of multiple sclerosis compared to those who are never infected.[7]

This is called molecular mimicry. The molecules mimic each other, in a sense. For example, the bacteria that causes strep throat (Streptococcus pyogenes) can lead to immune system cross-reaction with the heart muscle, causing rheumatic fever. This is a main reason why we give antibiotics for strep throat. Similarly, ankylosing spondylitis has been linked to Klebsiella pneumoniae; Guillain-Barré, to Campylobacter jejuni. Dozens of links have been discovered between various autoimmune conditions and viruses or bacteria.[9]

Environment

If the genetic component is important and infections frequently play a role, are autoimmune diseases basically just “luck of the draw” illnesses? No. That’s clearly not the whole picture, based on data related to other environmental exposures.

Rates of multiple sclerosis (MS), a disease that damages nerve sheaths, vary widely throughout the world. When I tell you that the rate of MS is higher the farther away a population is from the equator, how do you make sense of that?[10] How about the fact that those born in November have a slightly lower rate of MS and those born in May have a slightly higher risk than would be expected by random chance?[11] How are these connected? Does cold weather or some other seasonal factor somehow cause MS?

We now know that if migrants from a high-risk area move to a low-risk area, their risk becomes lower than that of their homeland population.[12] We obviously have to consider more than genes and viruses. Some other environmental exposure matters.

By environmental exposure, I mean food, exercise, tobacco, weather, environmental chemicals, X-rays, or basically anything to which we’re exposed. In the mystery of why MS is more common the farther from the equator you go, the answer is related to vitamin D: lower vitamin D levels are linked to a higher risk of MS and a higher risk of exacerbations if you already have the illness.[13][14] People farther from the equator have lower vitamin D levels. And babies born in the northern hemisphere in November compared to May have been in utero when their mom is more likely to have had better vitamin D status.

We make vitamin D when our skin is exposed to sunlight, so you can see how being far away from the equator might be linked to disease risk. We also know now that vitamin D is involved in immune system function.[15] Importantly, vitamin D supplements have not been shown to be helpful for multiple sclerosis.[16] You can’t take a nutrient supplement and get the same benefit for chronic disease (this principle has proven to be true many times in many studies).

What about nutrition? A population’s milk consumption is strikingly correlated with MS prevalence.[17] The more cow’s milk, the more MS. Molecular mimicry may play a role. Recall that MS damages nerve sheaths, the important covering on our nerve cells. It turns out that there’s a protein in cow’s milk that looks a lot like a protein on our nerve sheaths.[18] Our immune system reacts to both the cow’s milk protein and the nerve sheaths.

The link between dairy intake, autoimmune disease, and molecular mimicry doesn’t stop with MS. Type 1 diabetes, a disease in which the immune system attacks the insulin-producing cells of the pancreas, has also been linked to dairy. Again, the correlation between high dairy consumption in a population and disease rates is striking.[19] Patients with the disease have a strong immune response to proteins in milk that “mimic” components of the pancreas.[20] [21] Why does the immune system attack both the proteins in milk and the pancreas itself? Are exposures to milk proteins triggering the autoimmune process? This has been an ongoing hypothesis.

It may be that the timing of exposure to milk also plays an important role. The age at which an infant starts consuming solid foods seems to affect risk.[22] Breast milk appears to be protective.[23] One hypothesis has been that if infants are exposed to cow’s milk proteins too early, the proteins get through the wall of the gut and then play a role in initiating the autoimmune process. Animal studies support this idea. There is a type of rat that has been bred to have a high rate of type 1 diabetes; at the time of their weaning, exposure to cow’s milk protein leads to a dramatically increased incidence of type 1 diabetes.[24] Take away the milk protein and you can take away most of the diabetes.

But it gets even more complicated. It turns out you can also trigger type 1 diabetes in this animal model with gluten, the protein found in wheat, barley, and rye. If researchers withhold gluten at the time of weaning, they can quite strikingly prevent diabetes.[25] Gluten, of course, is also strongly linked to celiac disease. In fact, celiac disease does not exist without gluten. When exposed to gluten, the immune system goes a bit haywire in the intestinal wall and the resulting inflammation ends up greatly harming the intricate surface of the intestine. The disease is cured by removing gluten from the diet. (In related conditions, we also know that gluten can cause something called gluten ataxia, a debilitating disease causing loss of coordination and muscle function, and dermatitis herpetiformis, a skin rash; both of these, based on our current understanding, are rare.)

Of course, it’s not just cow’s milk and gluten that have been implicated in autoimmune disease. We know that the risk of inflammatory bowel disorders, Crohn’s colitis and ulcerative colitis, has been linked to infant feeding practices (breastfeeding being protective), cow’s milk, low intake of fiber and vegetables, and increased meat and added fats in the diet.[26] [27] Thyroid conditions are linked to iodine intake; both excessive and deficient intake can be problems.[28][29]

Gut Health

Partly from the research on celiac disease, we now know that part of the problem is a breakdown of the barrier in the intestine. This involves what is commonly known as leaky gut. The “seal” between the cells that line the gut, which keeps the outside food outside, breaks apart. Once the barrier is disrupted, incompletely digested material gets behind the first layer of cells in the gut. This can cause problems.

And if autoimmune diseases sometimes cluster together, as in the case of type 1 diabetes, celiac disease, and thyroid disease, might leaky gut be playing a common role?[30]

Of course, the health of the intestine is related to the health of the bacteria that live in the intestine. But despite the rampant claims for pills and potions sold on the internet for leaky gut, inflammation, and the microbiome, our current understanding of which bacteria exactly are good, what exactly they do, and how to best support them is in the early stages of research. Generally, we know that fiber and unrefined plant foods like leafy greens help to maintain a healthy diversity of beneficial bacteria in your intestine. This is consistent with research showing that Western diets high in meat, dairy, and saturated fats, and low in fiber, fruits, and vegetables are linked to some autoimmune diseases and increased inflammation in general.

Figure 1. The Autoimmune Formula

So, what do you take away from all this? I wish I could offer a simple explanation that answers the question about what causes autoimmune disease. But I can’t. I don’t think the science supports making blanket statements about autoimmune disease, but there are some key lessons we’ve seen so far that may be helpful.

As far as controllable factors, it seems that cow’s milk is, by far, the food most commonly linked to autoimmune disease. I suggest to my patients that they avoid all cow’s milk products. Second, avoid other components of a Western-style diet, meaning meat and added oils, and include plenty of fiber and green, yellow, and orange vegetables. Third, infant nutrition and breastfeeding may play a role, so I encourage moms to do everything they can to breastfeed. Fourth, get outside and get sun (without burning) and stay active regularly. Fifth, don’t smoke (smoking has been linked to some autoimmune diseases and is unhealthy for many other reasons too). Sixth, include some sea vegetables in the diet now and then or use iodized salt to ensure adequate iodine intake.

You may have noticed I didn’t mention gluten in my recommendations. I think it’s reasonable to avoid gluten, particularly if you have an autoimmune disease or are at risk, but you may want to discuss with your doctor about being tested for celiac disease before embarking on a gluten-free life. Despite the attention heaped on gluten, it is not as strongly implicated as cow’s milk in a broad array of autoimmune diseases. It is difficult to avoid gluten 100 percent of the time, and for most people, I’m not quite convinced it’s necessary. I have two full chapters on gluten in The China Study Solution (which is The Campbell Plan in hardcover).

By adhering to these strategies, will everyone avoid all autoimmune disease? Of course not. I believe it’s clear that autoimmune disease involves more than only nutrition, but nutrition is likely the single greatest modifiable risk factor for most people. And this isn’t just about prevention. There is now a smattering of evidence suggesting that diet can be an effective part of treating autoimmune disease.

In various publications, diet and lifestyle treatments have shown benefits in treating rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, Crohn’s colitis, multiple sclerosis, and even type 1 diabetes. We now know that once people are diagnosed with ulcerative colitis, consuming a more Western diet is linked to worse outcomes. Importantly, diet and lifestyle can also improve risks of related chronic diseases (many autoimmune conditions, for example, are linked to a higher risk of heart disease). So what have we got to lose in considering nutrition as part of the autoimmune conversation?

References

- Cooper GS, Bynum ML, Somers EC. Recent insights in the epidemiology of autoimmune diseases: improved prevalence estimates and understanding of clustering of diseases. Journal of autoimmunity 2009;33:197-207.

- NIH: The Autoimmune Diseases Coordinating Committee. Progress in Autoimmune Diseases Research: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2005.

- Ramos PS, Shedlock AM, Langefeld CD. Genetics of autoimmune diseases: insights from population genetics. Journal of human genetics 2015.

- Trynka G, Wijmenga C, van Heel DA. A genetic perspective on coeliac disease. Trends Mol Med 2010;16:537-50.

- Bogdanos DP, Smyk DS, Rigopoulou EI, et al. Twin studies in autoimmune disease: genetics, gender and environment. Journal of autoimmunity 2012;38:J156-69.

- Bach JF. Infections and autoimmune diseases. Journal of autoimmunity 2005;25 Suppl:74-80.

- Ascherio A. Environmental factors in multiple sclerosis. Expert review of neurotherapeutics 2013;13:3-9.

- Lauer K. Environmental risk factors in multiple sclerosis. Expert review of neurotherapeutics 2010;10:421-40.

- Cusick MF, Libbey JE, Fujinami RS. Molecular mimicry as a mechanism of autoimmune disease. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology 2012;42:102-11.

- Simpson S, Jr., Blizzard L, Otahal P, Van der Mei I, Taylor B. Latitude is significantly associated with the prevalence of multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 2011;82:1132-41.

- Dobson R, Giovannoni G, Ramagopalan S. The month of birth effect in multiple sclerosis: systematic review, meta-analysis and effect of latitude. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 2013;84:427-32.

- Gale CR, Martyn CN. Migrant studies in multiple sclerosis. Progress in neurobiology 1995;47:425-48.

- Duan S, Lv Z, Fan X, et al. Vitamin D status and the risk of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience letters 2014;570:108-13.

- Runia TF, Hop WC, de Rijke YB, Buljevac D, Hintzen RQ. Lower serum vitamin D levels are associated with a higher relapse risk in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2012;79:261-6.

- Aranow C. Vitamin D and the immune system. J Investig Med 2011;59:881-6.

- James E, Dobson R, Kuhle J, Baker D, Giovannoni G, Ramagopalan SV. The effect of vitamin D-related interventions on multiple sclerosis relapses: a meta-analysis. Mult Scler 2013;19:1571-9.

- Malosse D, Perron H, Sasco A, Seigneurin JM. Correlation between milk and dairy product consumption and multiple sclerosis prevalence: a worldwide study. Neuroepidemiology 1992;11:304-12.

- Guggenmos J, Schubart AS, Ogg S, et al. Antibody cross-reactivity between myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein and the milk protein butyrophilin in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol 2004;172:661-8.

- Dahl-Jorgensen K, Joner G, Hanssen KF. Relationship between cows’ milk consumption and incidence of IDDM in childhood. Diabetes Care 1991;14:1081-3.

- Monetini L, Barone F, Stefanini L, et al. Establishment of T cell lines to bovine beta-casein and beta-casein-derived epitopes in patients with type 1 diabetes. J Endocrinol 2003;176:143-50.

- Karjalainen J, Martin JM, Knip M, et al. A bovine albumin peptide as a possible trigger of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1992;327:302-7.

- Frederiksen B, Kroehl M, Lamb MM, et al. Infant exposures and development of type 1 diabetes mellitus: The Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY). JAMA pediatrics 2013;167:808-15.

- Egro FM. Why is type 1 diabetes increasing? Journal of molecular endocrinology 2013;51:R1-13.

- Daneman D, Fishman L, Clarson C, Martin JM. Dietary triggers of insulin-dependent diabetes in the BB rat. Diabetes research 1987;5:93-7.

- Funda DP, Kaas A, Bock T, Tlaskalova-Hogenova H, Buschard K. Gluten-free diet prevents diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 1999;15:323-7.

- Cashman KD, Shanahan F. Is nutrition an aetiological factor for inflammatory bowel disease? European journal of gastroenterology & hepatology 2003;15:607-13.

- Hou JK, Abraham B, El-Serag H. Dietary intake and risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:563-73.

- Duntas LH. Environmental factors and autoimmune thyroiditis. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 2008;4:454-60.

- Luo Y, Kawashima A, Ishido Y, et al. Iodine excess as an environmental risk factor for autoimmune thyroid disease. Int J Mol Sci 2014;15:12895-912.

- Kakleas K, Soldatou A, Karachaliou F, Karavanaki K. Associated autoimmune diseases in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). Autoimmunity reviews 2015;14:781-97.

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits