I’ve been around this diet and health realm for just a fraction of the time Dr. John McDougall was around it. I remember interviewing him for The China Study with my dad around 20 years ago and appreciating one of his incisive observations from his years of practice: “People love to hear good things about their bad habits.” How true this is.

This manifests in the preternatural ability for the same “Eat your favorite foods, get healthy” message to repeatedly spring back into the popular nutrition world. It is dusted off and resurrected every few years in some superficially different form; the darn thing just doesn’t go away. While the message evolves somewhat from book to book, the core is the same: Eat only your favorite richest foods and lose weight.

Of course, today I’m talking specifically about the low-carb message. It reached mass awareness with Dr. Atkins, then has returned in the overlapping messaging of The South Beach Diet, Protein Power, The Paleo Diet, a couple of antiwheat diets, and now the eat-fat diets. In conjunction with other books written in a more “scientific narrative” style by journalists Gary Taubes and Nina Teicholz, the low-carb message has been enjoying something of a renaissance over the past few years.

This is the ebb and flow of popular nutrition information, which I am convinced is unavoidable. Like the tides of the oceans, but much less calming, these familiar messages rise and fall. With my articles and books, I contribute to the tides of nutrition information as much as anyone else, but of course, I’m on the side of plant-based diets. So, let me explain how I interpret the latest round of low-carb messaging and why I remain disagreeable with its basic tenets. Let me specifically comment on its latest incarnation: fat will save us from the evils of carbs, specifically sugars and grains. Of course, as is probably true with all persistent messages, some important truths and lessons do emerge from the low-carb messages, and it’s important that we can understand, acknowledge, and incorporate them into our understanding of optimal nutrition.

The Recipe for a Low-Carb Book in Four Easy Steps

- Explain that the government nannies of the past 40 years have duped us into trying a low-fat experiment that has gone terribly awry. During that time, we’ve gotten fatter and sicker than ever while on a trial of a low-fat, practically vegetarian diet of unprecedented scale. (Tip: Mix in historical explanations of Ancel Keys leading us astray regarding saturated fat with lies, scientific dishonesty, and blustery ego.)

- Explain why we should ignore most nutritional science, particularly epidemiology, because observational research doesn’t count. Oh, and animal research really doesn’t count either. Oh, and human research also doesn’t count if it’s not randomized and controlled or if it’s too small or controversial. Oh, and also, it probably is rigged if it’s by someone with an “agenda,” who might even be suffering from the same personality defects that obviously afflicted Ancel Keys.

- Some science does count. Review this science, which includes randomized controlled trials favoring low-carb diets, studies showing no benefit of low-fat diets, and studies tangentially related.

- Tell people to eat lots of meat and added fats and take supplements that you sell. Sit back, relax, and enjoy your freshly cooked audience.

Part 1: The Setup

“It’s possible to think of the low-fat, near-vegetarian diet of the past half-century as an uncontrolled experiment on the entire American population, significantly altering our traditional diet with unintended results.” – Nina Teicholz, The Big Fat Surprise

It’s like the myth that the Inuit don’t have heart disease: If you repeat a falsehood often enough, it can very nearly seem truthful. The story has an intuitive appeal. We have all heard messages to eat less fat. We have been inundated with fat-free food products, including fat-free cookies, candies, and drinks. But the proliferation of these products doesn’t mean we have actually followed the recommendations.

In fact, we certainly have not been eating a low-fat diet. Neither have we been eating anything close to a near-vegetarian diet at any point in the past 50 years in America. To claim that we have been is ridiculous.

Low-carb authors refer to data showing that Americans have been eating more calories over the past several decades and that a disproportionate amount of those additional calories come from carbohydrates (mostly from sugar and refined grains). This means that our fat intake, as a percentage of total calories, has decreased slightly. But it does not mean we have been reducing the total amount of fat we eat. This is from a paper finding that fat intake, as a percentage of total calorie intake, has decreased:[1]

… although the percentage of energy from fat has decreased, the total amount of fat consumed has not decreased in the setting of an overall increase in energy intake, primarily from carbohydrates. Even normal-weight men and women consume at least 33% of calories from fat, which could be considered a high-fat diet as absolute fat intake has not decreased but the proportion is smaller because of the overall increase in energy intake (reference cited).

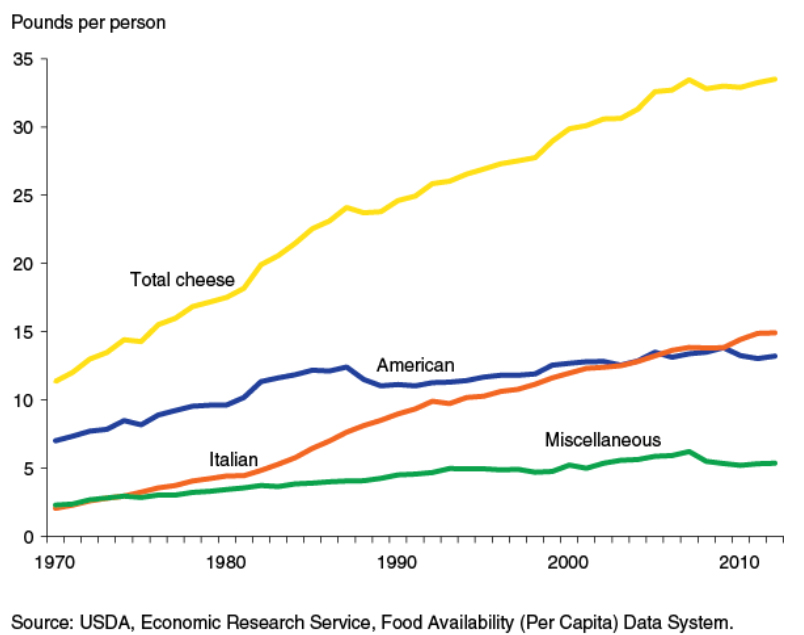

We’ve also continued eating lots of animal foods in addition to added fats. Added fat in the food supply has increased significantly since 1970, and the availability of cheese has dramatically increased over the past 40 years, according to the USDA.[2][3]

Total meat consumption has increased over the past 40 years, as it did throughout the 1900s.[4] While red meat has leveled off or decreased recently, we’ve more than made up for that with increased poultry consumption. This may be one of the most significant outcomes of the low-fat recommendations: Americans adding more poultry to their diet.

Let’s say you have a friend who eats scrambled eggs, toast and butter, and sausage for breakfast, a lunch of cold cut meat sandwiches with cheese and mayonnaise, and roast ham and baked beans for dinner. It’s the good ol’ standard American diet. Now, imagine your friend starts drinking several bottles of soda throughout the day and makes a few minor tweaks to their meals (grilled chicken with a smaller portion of ham, extra turkey sausage instead of normal sausage, margarine instead of butter, and extra cheese). Would you say they’re genuinely experimenting with a low-fat diet?

It’s true that refined carbohydrate consumption has increased disproportionately over the past 40 years.[5] But please, don’t characterize that as a low-fat dietary trial. That’s essentially what the setup of the low-carb formula claims, and it’s not truthful.

Part 2: Science Denial

“Many questioned Keys’ scientific conclusions, but he was vigorous in criticizing anyone who challenged him. He was a dominant, persuasive, and charismatic man who convinced the world of his hypothesis.” – Mark Hyman, MD, Eat Fat, Get Thin

The next step in the high-fat, low-carb book is to explain how we got it so terribly wrong with the low-fat message, with a brief review of the evidence. Ancel Keys is a popular figure to attack, because his work on heart disease was prominent and well-known. Many popular authors level a bunch of personal attacks at Keys, suggesting essentially that the low-fat history was based on his highly manipulated presentation of the data, questionable honesty, and bullying that forced the world to his point of view.

Of course, the fat recommendation was based on far more than diet and heart disease. Populations worldwide have been observed to have lower rates of not only heart disease while consuming a lower fat, particularly animal fat, diet, but also diabetes and cancer.[6] [7]Referencing both observational studies and animal experiments, the prominent 1982 Diet, Nutrition, and Cancer expert panel report said, “The committee concluded that of all the dietary components it studied, the combined epidemiological and experimental evidence is most suggestive for a causal relationship between fat intake and the occurrence of cancer.”[8]

A necessary part of any low-carb message is explaining away the data showing lower rates of common Western diseases in populations eating more plant-based diets that are lower in added fats and sugars. The way they achieve this is to say that observational studies show correlations but cannot prove causation. This statement is correct, but don’t take the next step in believing that observational research should be thrown out.

If you look around the world and see that most healthy, trim traditional populations with low rates of common chronic Western diseases ate a relatively unprocessed, low-fat plant-based diet, it seems to me that you have a very steep hill to climb by claiming that the polar opposite diet, a high-fat, high-meat diet, is actually the real key to longevity and health. Observations can generate hypotheses for further research and reveal context to come back to for evaluating results from other types of studies.

Another strategy is for the low-carb proponents to point out the inaccuracies of observational research. This is also valid. Dietary surveys can be susceptible to inaccuracies. But these inaccuracies are more often likely to lead to a null result when a relationship between two variables may exist. When you find relationships between diet and disease, and when you start to see consistent findings that plants or plant components are linked to healthier outcomes, it becomes a more convincing finding, especially when it has been shown that the relationship is biologically plausible.

Yet another strategy is claiming that research is too small or controversial (even if it’s just controversial among those who don’t like its findings). Reverse heart disease? Early-stage prostate cancer? Turn bad genes off and good genes on? It must be too small a group or too controversial. These arguments are superficial and unconvincing.

Part 3: The “Good” Science that Counts.

Some science does matter, of course, according to low-carb advocates. This science comes in three flavors: Research showing no relationship between fat and disease, research favoring very low-carbohydrate diets, and science that seems related but is actually tangential to the claims at hand. Let’s call these the three sisters of the low-carb message. At the end, you can harvest a menu plan full of meat and fat.

1) The “no relationship” studies

Tons of studies show no relationship between diet and disease, including some exceptionally well-done studies. Take, for example, the Women’s Health Initiative, which found that a modestly lower fat diet did not significantly reduce the risk of breast cancer or heart disease. Notice I said lower, not low: the study subjects only got down to about a 25% fat diet briefly before slipping, and they ended the study closer to a 30% fat diet. This is a valuable finding. We now know that maintaining a Western-style dietary pattern and choosing low-fat meats and low-fat dairy for a few years—using poultry instead of red meat, for example—is unlikely to make a big dent in cancer or heart disease rates. They found that a transient, modest reduction in fat intake alone while not altering the overall dietary pattern (the diet remained very high in animal-based foods and very low in fiber and antioxidants) does little. There was marginal, transient weight loss among subjects and no significant benefit on chronic disease.

Great! This is a valuable finding, and I think this was an amazing study for its scope and execution. But let’s be careful how we discuss these results. It doesn’t prove that fat is healthy. It doesn’t prove that there’s no benefit from all types of low-fat diets. It doesn’t confirm or deny the promise of the original dietary patterns seen in observational studies for preventing breast cancer or heart disease. It did not test predominantly plant-based dietary patterns low in processed food. Was it interesting? Yes. Useful? Sure. Proof there’s no harm from consuming high-fat animal-based diets? No way.

Studies can show no relationship between diet and disease for numerous reasons, even if there is a strong relationship between diet and disease. We should be wary of any arguments that use a null result as evidence after they throw away mountains of research in the previous breath.

2) Pro-low carb studies

Several short-term trials have shown that very low carbohydrate, high-fat diets may result in lower weight, insulin, and blood sugar and higher HDL (the “healthy” cholesterol, though this moniker is flawed).[9] Some well-done studies also show that lots of added sugar is bad in numerous ways (added sugar is not the same as whole, fresh fruit).[10][11] Added sugar is more than just empty calories. It will rot your teeth, worsen your cholesterol panel, and increase fat inside and outside your body. It will make your diet more nutrient deficient, contribute to excess calorie intake, and fuel an addictive relationship that encourages processed food consumption.

In addition, studies have shown the Mediterranean diet is healthy. Mediterranean diets are generally more plant-based, with fish and vegetable oils (mostly canola or olive oils), and reduced animal foods. They have shown benefits for dementia and heart disease compared to the standard Western diet. In fact, if you take someone eating a high-fat, standard Western diet and tell them to instead consume a Mediterranean diet with a liter of olive oil weekly, they can significantly reduce stroke risk.[12] This provides fuel for the argument that added fats (olive oil, in this case) are healthy.

While interesting, this study is extra confusing for the public because the press communicating its findings called the high-fat control diet a low-fat diet. This is because the researchers suggested people in the control arm limit their fat; the problem is that none of the study subjects actually lowered their fat consumption significantly. They consumed a very high-fat diet throughout the study and marginally decreased their fiber intake. Nonetheless, the intervention utilizing a Mediterranean diet with olive oil demonstrated reduced strokes. And there was a trend to fewer heart-related issues as well. Collectively, there was a 30% reduction in heart attacks, strokes, and deaths from either of these. Regarding heart attacks specifically, the number of heart attacks was 3.1 per 1000 people per year in the olive oil group compared to 3.9 per 1000 people per year in those eating the high-fat control diet.[12] Does this mean olive oil is a keystone of the optimal diet?

A low-carb book usually doesn’t get into these questions. It suffices to cite the study and say that added oils reduce cardiovascular disease.

3) Tangential Information

Finally, a portion of the science in any low-carb book is tangential biomedical facts. For example, we know that fat is crucial in a wide variety of functions throughout the body. It is important in making surfactant, which allows our lungs to function. It is important in brain function. In fact, the brain is 60% fat.

While these facts are interesting and true, are they relevant to nutritional intake? “Eat more fat to build a better brain” makes for a catchy story, but nutrition and physiology don’t work that way. They are more complicated than that. We can’t eat lungs and expect to breathe better, for example.

Hopefully, you’re beginning to see how a fad diet book is created. You can claim that we’ve trialed a low-fat (almost vegetarian!) diet while getting fatter and more diabetic than ever and that we got here by worshiping useless observational research. Accordingly, it turns out that personally flawed, compromised researchers, namely Ancel Keys, pulled the wool over the world’s eyes for their own egos and agendas. Looking at the more recent research that counts, we can now put together a story with plenty of citations that show no benefit of the prevailing recommendation to consume low-fat diets, highlight the dangers of added sugars, and indicate short-term benefits for low-carb diets on certain biomarkers (weight, triglycerides, glucose, HDL cholesterol). We can even explain the benefits using tangential facts (feed the brain, which is fat, etc.).

The layperson can very quickly get mightily confused. It seems so scientific!

It’s important to learn from the studies showing certain benefits of low-carbohydrate diets. These are the three main lessons:

- Americans consume vast quantities of junk carbohydrates. That’s pretty much all the carbohydrates we consume—mammoth amounts of added sugars and white flour, which are usually packaged with added fats. I opened the freezer at work the other day to find a box of frozen waffles flavored as “chocolate chip muffins” that someone had brought in. It seems that there are no limits anymore to the candyfication of our foods. Many cereals, for example, are blatantly marketed as flavors of our favorite candies. While marketed differently, adult “healthy” cereals often have just as much added sugar and fat. Different industrial formulations of refined sugars, flours, flavorings, salt, and oil occupy the bulk of the middle of every grocery store, and people can achieve enormous health gains by eliminating this junk. I always applaud patients for lowering their consumption of these junk carbohydrates. It may be the most beneficial dietary improvement many consumers can make, and the low-carbohydrate research has contributed valuable insight into this problematic aspect of Western diets.

- Calories matter. I don’t suggest counting calories or portions, but the fact is that if you choose a diet that automatically and significantly restricts calories, you may have significant health benefits, regardless of the type of diet.

- The problem (or solution) has never been and will never be a single food component. Our health problems cannot be ascribed solely to carbohydrates, fat, protein, fiber, cholesterol, antioxidants, or any other single food component. There has been vast confusion generated by people tinkering with one nutrient at a time, assigning blame or salvation to a different food component without looking at their overall dietary pattern. All food components work together to create or undermine health.

Unfortunately, in addition to discounting broad swaths of science, the low-carb claims outright ignore other research. Very low-fat, plant-based diets with minimal processed foods have been observed to correlate with very low heart disease rates.[13] In animal and human studies, they lower cholesterol.[14][15] They cause weight loss.[16] Most importantly, they can reverse advanced heart disease, something that has never been shown with a high-fat diet containing meat.[17][18]

Animal studies show that very low-carbohydrate, high-fat diets may improve biomarkers while decimating the arteries, growing atherosclerotic plaques at a far more prodigious rate than a lower-fat, higher-fiber diet.[19] We now know that fiber-rich plant foods increase the body’s production of endothelial progenitor cells, the repair cells that bolster the vital lining of your blood vessels.[20] And we know that humans in some of these very low-carbohydrate dietary trials show no improvement of their arterial function (flow-mediated dilatation) after a period on the diet, sometimes even worsening their arterial function, even though other biomarkers may improve.[21][22] Observational studies find that those people eating lower carbohydrate diets have poorer functioning small arteries and a higher risk of death, particularly death from heart disease.[23]–[26]

We could go through a similar exploration of ignored evidence linking low-fat, unprocessed plant-based diets and reduced burden of diabetes and obesity.

There’s a lot of discussion about fat and brain health. People ask me about the risk of dementia from a low-fat diet, having heard that added fats are essential for brain health. Cardiovascular disease (blood vessel disease) plays a large role in dementia, and I just mentioned a small sample of research that suggests the diet best for your blood vessels is a whole-food, plant-based diet naturally low in fats. This will help your brain. We also know that whole-food, plant-based diets naturally low in fat can prevent and reverse diabetes and metabolic syndrome, which are also linked to dementia.

East Asian and Pacific populations that have been noted historically to have lower rates of Alzheimer’s dementia have traditionally eaten a more plant-based diet lower in fat.[27] Their diet and lifestyle are changing, with significantly increasing rates of Alzheimer’s dementia in the Pacific region. This comes after several decades of a dietary transition, characterized in China by increasing animal foods and added oils and decreasing whole grains and beans (and only more recently added sugars).[28] In populations followed over time, those who eat a more plant-rich Mediterranean diet, marked by more fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and fish, less red meat and dairy, more unsaturated fats than saturated fats, and moderate alcohol consumption, have dramatically lower rates of cognitive impairment and dementia.[29] This is a dramatically different diet from the low-carb diets popularly espoused. This is actually a relatively high-carbohydrate diet.

I have no concerns about the risk of dementia on a no–added oil, whole-food, plant-based diet supplemented with B12. In fact, I have concerns about brain health in people consuming a diet with lots of added fat and animal foods.

Finally, lots of evidence is left out or discarded in the low-carb formula. Even worse, evidence is presented inaccurately or without references, so the veracity of the claims can’t be checked. In a more recent popular book, Dr. Ornish’s study results were incorrectly characterized. The author writes that the low-fat group gained weight; in fact, they lost weight. An important metabolic study was inaccurately described. The author writes that the low-carb subjects burned more calories, which was the opposite of the actual finding; the low-fat group burned more calories. I trust these are honest mistakes, but the consistent omission or discounting of contextual research is a more problematic, obviously deliberate strategy of science denialism in most low-carbohydrate plans.

Part 4: The Payoff

The most important part of the low-carbohydrate formula is to tell people they can eat their favorite “bad” foods abundantly and get trim and healthy. This is where the food guides and recipes (and supplements) come in.

In a recent popular book, readers are asked to eliminate all grains, sweeteners, beans (with a couple exceptions), starchy plants (except for optional 2–4 cups, maximum, per week, of limited starchy foods), and all fruit (except for small amounts of select fruit). Other things are also off the menu, including refined oils, dairy, gluten, and alcohol.

Even if one were to eat a salad with every meal, restricting this many starchy plants would mean that most of the calories provided by this diet would come from added fats or meats. Even if people eat pounds of non-starchy veggies, it will only amount to a few hundred calories a day (and, of course, most readers won’t come close to consuming pounds). For most, the vast majority of calories consumed on this diet will be provided by fat and protein; in other words, it’s another low-carbohydrate, high-fat, high-protein diet.

The recipes in this particular book are consistent with this. About 75% of the recipes are centered on meat. The rest are focused on fat (coconut oil, avocado, olive oil, nuts, etc.).

Additionally, no fewer than 11 supplements are recommended at baseline, with four additional supplements listed as optional. You can conveniently buy the first 21-day supply for $213 on the author’s website.

So there you have it. If you can write clearly and communicate well, you now have the recipe to write a low-carbohydrate book. You better do it quickly, though. This incarnation of the low-carb diet will only be here for a short while. It’ll come back later as a slightly different message, perhaps focusing on protein again.

Or perhaps, more optimistically, the argument for plant-based diets, based on sound science, will continue to gain momentum, and we’ll move beyond the low-carb diet cycle. I surely hope so!

References

- Austin GL, Ogden LG, Hill JO. Trends in carbohydrate, fat, and protein intakes and association with energy intake in normal-weight, overweight, and obese individuals: 1971-2006. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;93:836-43.

- Wells HF, Buzby JC. Dietary Assessment of Major Trends in U.S. Food Consumption, 1970-2005: Economic Information Bulletin Number 33: Economic Research Service; March 2008.

- Trends in U.S. Per Capita Consumption of Dairy Products, 1970-2012. United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, 2014. (Accessed April 15th, 2016, 2016, at http://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2014-june/trends-in-us-per-capita-consumption-of-dairy-products,-1970-2012.aspx#.VxD9d8dHIuU.)

- Daniel CR, Cross AJ, Koebnick C, Sinha R. Trends in meat consumption in the USA. Public Health Nutr 2011;14:575-83.

- Johnson RK, Appel LJ, Brands M, et al. Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2009;120:1011-20.

- Himsworth H. Diet and the incidence of diabetes mellitus. Clinical Science 1935;2:117-48.

- Carroll KK. Experimental evidence of dietary factors and hormone-dependent cancers. Cancer Res 1975;35:3374-83.

- Assembly of Life Sciences (U.S.). Committee on Diet Nutrition and Cancer. Diet, nutrition, and cancer. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1982.

- Hite AH, Berkowitz VG, Berkowitz K. Low-carbohydrate diet review: shifting the paradigm. Nutrition in clinical practice : official publication of the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 2011;26:300-8.

- Stanhope KL, Medici V, Bremer AA, et al. A dose-response study of consuming high-fructose corn syrup-sweetened beverages on lipid/lipoprotein risk factors for cardiovascular disease in young adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;101:1144-54.

- Lustig RH, Mulligan K, Noworolski SM, et al. Isocaloric fructose restriction and metabolic improvement in children with obesity and metabolic syndrome. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015.

- Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvado J, et al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet. N Engl J Med 2013.

- Campbell TC, Parpia B, Chen J. Diet, lifestyle, and the etiology of coronary artery disease: the Cornell China study. Am J Cardiol 1998;82:18T-21T.

- Kritchevsky D. Dietary protein, cholesterol and atherosclerosis: a review of the early history. The Journal of nutrition 1995;125:589S-93S.

- Ferdowsian HR, Barnard ND. Effects of plant-based diets on plasma lipids. Am J Cardiol 2009;104:947-56.

- Barnard ND, Levin SM, Yokoyama Y. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Changes in Body Weight in Clinical Trials of Vegetarian Diets. J Acad Nutr Diet 2015.

- Ornish D, Scherwitz LW, Billings JH, et al. Intensive lifestyle changes for reversal of coronary heart disease. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 1998;280:2001-7.

- Esselstyn CB, Jr., Gendy G, Doyle J, Golubic M, Roizen M. A Way to Reverse CAD? J Fam Pract 2014;63:356-64b.

- Foo SY, Heller ER, Wykrzykowska J, et al. Vascular effects of a low-carbohydrate high-protein diet. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:15418-23.

- Mano R, Ishida A, Ohya Y, Todoriki H, Takishita S. Dietary intervention with Okinawan vegetables increased circulating endothelial progenitor cells in healthy young women. Atherosclerosis 2009;204:544-8.

- Ruth MR, Port AM, Shah M, et al. Consuming a hypocaloric high fat low carbohydrate diet for 12weeks lowers C-reactive protein, and raises serum adiponectin and high density lipoprotein-cholesterol in obese subjects. Metabolism 2013.

- Ballard KD, Quann EE, Kupchak BR, et al. Dietary carbohydrate restriction improves insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, microvascular function, and cellular adhesion markers in individuals taking statins. Nutr Res 2013;33:905-12.

- Merino J, Kones R, Ferre R, et al. Negative effect of a low-carbohydrate, high-protein, high-fat diet on small peripheral artery reactivity in patients with increased cardiovascular risk. The British journal of nutrition 2013;109:1241-7.

- Fung TT, van Dam RM, Hankinson SE, Stampfer M, Willett WC, Hu FB. Low-carbohydrate diets and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: two cohort studies. Ann Intern Med 2010;153:289-98.

- Sjogren P, Becker W, Warensjo E, et al. Mediterranean and carbohydrate-restricted diets and mortality among elderly men: a cohort study in Sweden. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2010;92:967-74.

- Trichopoulou A, Psaltopoulou T, Orfanos P, Hsieh CC, Trichopoulos D. Low-carbohydrate-high-protein diet and long-term survival in a general population cohort. European journal of clinical nutrition 2007;61:575-81.

- Chen C, Homma A, Mok VC, et al. Alzheimer’s disease with cerebrovascular disease: current status in the Asia-Pacific region. J Intern Med 2016.

- Zhai FY, Du SF, Wang ZH, Zhang JG, Du WW, Popkin BM. Dynamics of the Chinese diet and the role of urbanicity, 1991-2011. Obes Rev 2014;15 Suppl 1:16-26.

- Morris MC, Tangney CC, Wang Y, Sacks FM, Bennett DA, Aggarwal NT. MIND diet associated with reduced incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 2015.

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits