In Part 1 of this series I discussed the origins of the ketogenic diet and the biological role of ketone bodies. In Part 2 I then addressed the question of whether a ketogenic diet (and, by extension, living in a state of near-permanent ketosis) is natural to humans. But the truth is that most people who are attracted to the ketogenic diet don’t really care about these issues: they just want to know if it will help them lose weight. And that’s what I’m going to cover in this article.

The ‘carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis’ is central to the ketogenic diet philosophy. It states that eating a high-carbohydrate diet drives insulin levels up. This causes fat to accumulate in adipose tissue and suppresses energy expenditure, thus lowering the metabolic rate. Simply put, according to advocates of the ketogenic diet, eating ‘carbs’ causes excessive insulin production which makes us fat. They claim[1] that ketogenic diets offer a metabolic advantage over every other type of weight loss diet, including low-carb diets that aren’t ketogenic. According to them, exchanging calories from carbohydrates for calories from fat will have several beneficial outcomes: it will drive down insulin levels, increase energy expenditure and metabolic rate, increase the release of fat from our adipose tissue stores, increase the oxidation of fat as a fuel, and ultimately result in an increased loss of body fat. ‘A calorie is not a calorie’ they state.

But what does the science say?

Putting Ketogenic Diets to the Test

First of all, ketogenic diets don’t demonstrate any ‘metabolic advantage’ compared to standard low-carbohydrate weight loss diets that are not ketogenic, according to a 2006 study[2] which found no significant difference in weight loss or body fat loss in obese adults who were randomly assigned to either a ketogenic diet (60% energy from fat, and 5% from carbohydrate) or a non-ketogenic low-carbohydrate diet (30% of energy from fat, and 40% from carbohydrate) for 6 weeks.

However, one participant assigned to the ketogenic group developed cardiac arrhythmias (a known side-effect of ketogenic diets) during the first week of the study and had to drop out. The inflammatory risk profile also increased amongst the ketogenic dieters, and they reported lower vigor and poor mood.

The claim that cutting dietary carbohydrate results in a greater loss of body fat than cutting dietary fat because it increases the amount of fat oxidized as fuel was put to the test in 2015[3]. 19 obese adults were confined to a metabolic ward (i.e. a dedicated research facility where the only food consumed was that supplied by the researchers) for 2 x two-week periods to test the effects of a high carbohydrate, reduced fat versus reduced carbohydrate, high fat diet. The volunteers did 1 hour of exercise per day on a treadmill, and were otherwise sedentary during their time on the metabolic ward.

For the first 5 days of the study, they were fed a baseline diet of 50% carbohydrate, 35% fat, and 15% protein. Then, they were put on one of the test diets: a reduced carbohydrate diet (50% of daily calories from fat, 30% from carbohydrate) or a reduced fat diet (72% carbohydrate, 8% fat). After a two to four-week ‘washout’ period, they then swapped over to the other diet, so that their results on each diet could be compared. Both test diets contained 30% fewer calories than the participants’ customary diets, with the reduction being achieved either by cutting fat or cutting carbohydrates. The protein content of both test diets was the same (20% of daily calories) so that researchers could directly compare the effects of reducing dietary fat versus carbohydrate on weight loss.

And the results were…

As predicted by the carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis, insulin secretion dropped when participants were on the carbohydrate-restricted diet, and the amount of fat they were burning for fuel increased. However, participants lost more body fat while eating the low-fat diet (an average of 89 g per day) than when they were on the low-carbohydrate diet (53 g per day), despite having higher insulin levels and less fat oxidation! As the researchers concluded:

“This study demonstrated that, calorie for calorie, restriction of dietary fat led to greater body fat loss than restriction of dietary carbohydrate in adults with obesity. This occurred despite the fact that only the carbohydrate-restricted diet led to decreased insulin secretion and a substantial sustained increase in net fat oxidation compared to the baseline energy-balanced diet.”

In other words, most of the extra fat that participants burned when they were carbohydrate-restricted came from their diet rather than their fat stores. On the other hand, when participants ate a diet lower in fat, they burned less fat and more carbohydrate to fuel their bodies, but ended up losing more body fat.

However, ketogenic diet supporters still didn’t accept these findings, because according to them the low-carbohydrate diet used in this study wasn’t low-carb enough – after all, it comprised 30% of energy from carbohydrates. A truly ketogenic diet, they said, would have resulted in more fat loss due to the ‘metabolic advantage’.

Any weight loss that you do manage to achieve on a ketogenic diet comes at the cost of a higher risk of death, especially from heart disease and cancer.

To answer to this objection the researchers tested a truly ketogenic diet the following year[4]. 17 overweight or obese men were confined to a metabolic ward for eight weeks. For the first four weeks, they were fed a baseline diet comprising 50% carbohydrate, 15% protein and 35% fat. This was followed by four weeks on a ketogenic diet (5% carbohydrate, 15% protein, 80% fat) with the same number of calories as the baseline diet. Their energy expenditure was measured during sleeping and waking periods, and their changes in body composition were measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans. Additionally, they were prescribed 90 minutes of low-intensity aerobic exercise per day on an exercise bike.

And the results were…

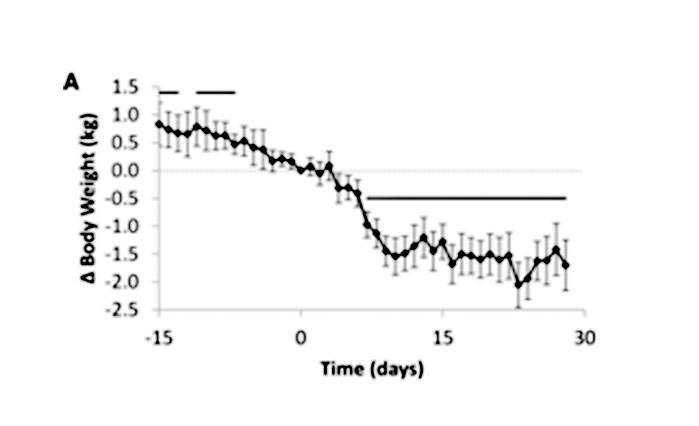

Although the baseline diet was not intended to cause weight nor fat loss, subjects lost 0.8 kg in the last 15 days of the diet, including 0.5 kg of body fat loss. However, despite a small increase in energy expenditure on the ketogenic diet, body fat loss actually slowed down when compared to fat loss on the high carbohydrate diet.

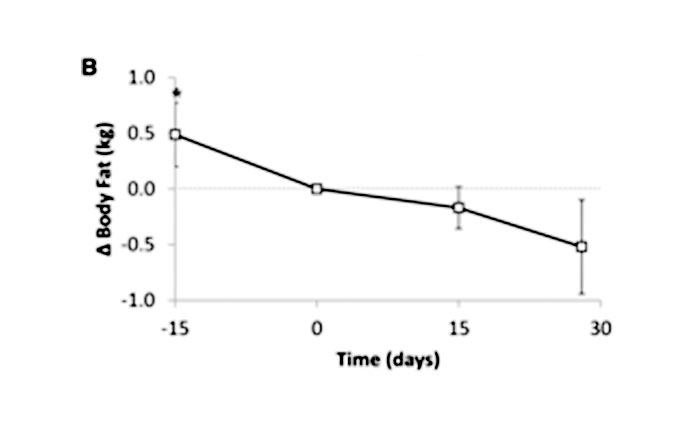

The diagram below illustrates the fat mass loss during this study. The slope is steeper, meaning quicker fat loss, in the last 15 days of the 50% carbohydrate baseline diet (-15 to 0 days). Then, in the first 15 days of the ketogenic diet (0 to 15 days), the slope is less steep, meaning slower fat loss. The participants took the entire 30 days on the ketogenic diet to lose the same amount of fat they lost during the last 15 days of the higher carbohydrate diet.

Participants experienced a rapid loss of 1.6 kg of overall weight during the first 15 days of the ketogenic diet phase, with a total loss of 2.2 kg during their 30 days on it.

As stated before, only 0.5 kg of the 2.2 kg was body fat loss despite a 47% reduction in insulin levels. Consequently, these results do not support the carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity.

To make matters worse, fat-free mass (muscle and bone) declined on the ketogenic diet. Urinary nitrogen excretion also increased, indicating significantly increased protein utilization. To recap, certain cells in the body, including brain, kidney, and red blood cells are almost completely dependent on glucose as an energy source. If insufficient carbohydrates are supplied, then the body will break down protein to turn its amino acids into glucose to fuel these cells.

So what did this meticulously-conducted study reveal about weight loss on a ketogenic diet? As explained in part 1, the initial rapid weight loss that lures people into following these diets is mostly from the depletion of glycogen and the water it holds. However, ketogenic diets are not good for fat loss, which is, after all, what counts when trying to lose weight. Instead, they deplete fat-free tissues, such as the vital muscle mass which maintains a healthy metabolic rate and helps to prevent weight gain as we age. So why don’t ketogenic diets work for fat loss? The researchers hypothesized:

“We suspect that the increased dietary fat resulted in elevated circulating postprandial [after-meal] triglyceride concentrations throughout the day, which may have stimulated adipose tissue fat uptake… and/or inhibited adipocyte lipolysis [breakdown of fat from fat cells, to use for energy production]. These physiologic questions deserve further study, but it is clear that regulation of adipose tissue fat storage is multifaceted and that insulin does not always play a predominant role.”

Does the Ketogenic Diet Suppress Appetite?

It is well known that weight loss can result in an increased appetite[5], and this is one of the primary reasons why most diets fail. Keto enthusiasts claim that weight loss, and the maintenance of weight-loss goals, is easy on a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet because ketone bodies suppress appetite while in ketosis. This then prevents the resulting increase in appetite that usually sabotages the dieter’s best intentions.

However, a study[6] of the effects of an eight week low-energy ketogenic diet on hunger perception and appetite hormones in obese men and women found that appetite was increased in the first three weeks of the diet, then tapered off for the remaining five weeks. Unfortunately, once participants returned to a normal energy intake, their appetites came back strongly: both hunger feelings and the concentration of the ‘hunger hormone’, ghrelin, were significantly higher than at baseline, before they started the diet.

What Actually Works for Weight Loss?

Here’s the real surprise: the most effective dietary intervention for long-term weight loss ever published in a peer-reviewed journal, the BROAD Study, used the opposite of a ketogenic diet. Overweight and obese patients from a single GP practice in Gisborne, New Zealand ate a low fat (< 15% of daily calories from fat), high carbohydrate, whole food, plant-based diet. Participants were instructed to eat ad libitum (until they were full, with no portion control) and were not prescribed any exercise. Weight loss at six months averaged 12.1 kg, and at twelve months, 11.5 kg. As the authors concluded:

“To the best of our knowledge, this research has achieved greater weight loss at six and twelve months than any other trial that does not limit energy intake or mandate regular exercise.”

The BROAD Study’s findings should not have caught anyone by surprise. Back in 2001, the Continuing Survey of Food Intake by Individuals found that people with the highest carbohydrate intake had the highest nutritional quality and the lowest body mass index (BMI), while those eating diets which derive less than 30% of their energy from carbohydrates were found to have the lowest micronutrient and fiber intakes and the highest BMI

So Why Is There Such Enthusiasm for the Ketogenic Diet?

There is no doubt that many people do experience rapid weight loss when they adopt a ketogenic diet. Unfortunately, most don’t realise that the plummeting numbers on the scales are primarily from depletion of glycogen, water and lean tissue rather than the body fat that they’re desperate to shed.

People eating a ketogenic diet tend to eat fewer calories, partly because the diet is quite monotonous and not very appealing (there’s only so much bacon, eggs, cheese, avocado and oil that the average person can stomach, and many people become nauseated by the high fat intake), and partly because ketone bodies do have an appetite-suppressing effect. As the authors of a review of low carbohydrate diets[9] concluded, “participant weight loss while using low-carbohydrate diets was mostly associated with decreased caloric intake and increased diet duration but not with reduced carbohydrate content.” There is no ‘metabolic advantage’ to ketogenic diets; at the end of the day, the research literature shows that a calorie is still a calorie, and if you eat less calories, you’ll lose weight.

However, maintaining that weight loss over the long term on a ketogenic diet is challenging. The lack of palatability of ketogenic diets, and the brain’s unquenchable desire for its preferred fuel – carbohydrates – results in difficulties adhering to the diet after the initial rapid weight loss. A review of studies using very low carbohydrate diets for type 2 diabetes[10] found that 1 year after being assigned to the low-carb diet group, with instructions to eat less than 50 g of carbohydrate per day, participants were eating between 132 and 162 g per day. The sheer number of articles on how to fend off carbohydrate cravings that appear on ketogenic diet websites reveals the extent of the problem. And as soon as people begin to eat more of the carbohydrates that their bodies are urging them for, they go out of ketosis and their appetite returns with a vengeance.

To top it all off, any weight loss that you do manage to achieve on a ketogenic diet comes at the cost of a higher risk of death[11], especially from heart disease and cancer[12]. Low carbohydrate diets impair flow-mediated dilatation[13], an important marker of the health of your arteries. Animal studies reveal that high fat diets have adverse effects on cognition, memory and mental well-being; induce metabolic dysfunction, intestinal hyperpermeability (‘leaky gut’), inflammation and liver damage; and raise the risk of osteoporosis[14].

No one embarking on a weight loss program aims to become the skinniest corpse in the morgue. Switching to a whole food, plant-based diet not only facilitates a sustainable reduction in energy intake and inherent long-term body fat loss without deprivation but also improves nutritional quality, overall health and decreases the risk of premature death. Why settle for anything less than this?

References

- Manninen, A.H. (2004), Is a calorie really a calorie? Metabolic advantage of low-carbohydrate diets. J Int Soc Sports Nutr.;1(2):21-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2129158/

- Johnston, C.S., Tjonn, S.L., Swan, P.D., White, A., Hutchins, H. & Sears, B. (2006), Ketogenic low-carbohydrate diets have no metabolic advantage over nonketogenic low-carbohydrate diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 83(5):1055-61. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16685046

- Hall, K.D., Bemis, T., Brychta, R., et al (2015), Calorie for Calorie, Dietary Fat Restriction Results in More Body Fat Loss than Carbohydrate Restriction in People with Obesity. Cell Metab. 22(3):427-36. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26278052

- Hall, K.D., Chen, K.Y., Guo, J. et al (2016), Energy expenditure and body composition changes after an isocaloric ketogenic diet in overweight and obese men. Am J Clin Nutr. 104(2):324–333. https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/104/2/324/4564649

- Cornier, M.A. (2011), Is your brain to blame for weight regain? Physiol Behav. 104(4):608-12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21496461/

- Nymo, S., Coutinho, S.R., Jørgensen, J., Rehfeld, J.F., Truby, H., Kulseng, B. & Martins, C., (2017), Timeline of changes in appetite during weight loss with a ketogenic diet. Int J Obes. 41(8):1224-1231.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28439092 - Wright, N., Wilson, L., Smith, M., Duncan, B. & McHugh, P., (2017), The BROAD study: A randomised controlled trial using a whole food plant-based diet in the community for obesity, ischaemic heart disease or diabetes. Nutr Diabetes. 7(3):e256. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28319109

- Kennedy E.T., Bowman, S.A., Spence, J.T., Freedman, M., King, J. (2001), Popular diets: correlation to health, nutrition, and obesity. J Am Diet Assoc.;101(4):411-20.

- Bravata, D.M., Sanders, L., Huang, J., Krumholz, H.M., Olkin, I., Gardner, C.D. & Bravata, D.M. (2003) Efficacy and safety of low-carbohydrate diets: a systematic review. JAMA;289(14):1837-50.

- van Wyk, H.J., Davis, R.E., Davies, J.S. (2016), A critical review of low-carbohydrate diets in people with Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med.;33(2):148-57.

- https://empowertotalhealth.com.au/low-carb-deja-vu/

- https://empowertotalhealth.com.au/eating-low-carb-get-your-facts-straight-your-life-depends-on-it/

- Buscemi, S., Verga, S., Tranchina, M.R., Cottone, S., Cerasola, G. (2009), Effects of hypocaloric very-low-carbohydrate diet vs. Mediterranean diet on endothelial function in obese women. Eur J Clin Invest. 39(5):339-47.

- Brouns F. (2018), Overweight and diabetes prevention: is a low-carbohydrate-high-fat diet recommendable?. Eur J Nutr.;57(4):1301-1312.

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits