What are the benefits of pure vegetarian or vegan diets? How about a whole food, plant-based (WFPB) lifestyle—what threshold of so-called purity must you reach to optimize your health? The answer depends on your perspective. If you are choosing to avoid animal products for ethical reasons, I would think you would want to be as close to 100 percent as possible. But what about those choosing WFPB nutrition for health reasons?

For years, I have answered this question simply: the closer we get to a 100 percent WFPB lifestyle, the healthier we will be. It may, however, surprise some to learn that I am not aware of any verifiable evidence that 100 percent purity is needed to optimize health for all people at all times; the reason I recommend getting as close to 100 percent WFPB as possible is that dietary addictions—to dietary fat or refined carbohydrates, for example—make it difficult for us to eat only small amounts of unhealthy foods while remaining on the WFPB path. In many ways, it can be easier to transition fully rather than 90 percent.

We understand this intuitively from other health and lifestyle choices. We would probably not recommend someone cut down to one-tenth as many cigarettes as before they decided to quit smoking because we know that as long as some fragment of the unhealthy habit remains, they may be at risk of reverting. Our dietary choices are similar; tastes change more completely with a prolonged absence of addictive substances.

No, Not Veganism

Despite recommending a lifestyle as close to 100 percent WFPB as possible, I have tended to avoid the words vegan and vegetarian because these practices have mostly been driven by ideologies based on ethical considerations. While those ethical considerations are praiseworthy and sufficient rationales for many people, my motivation for questioning the standard American diet (SAD) is based on science. I was not even aware of these words when I began my experimental research program, more than 60 years ago. I was only interested in scientific research, and I had been raised to believe meat, milk, and eggs deserved their place at the center of our plates.

When our studies started to indicate a very different and provocative conclusion on the health value of animal protein, I was prompted to seek a new label, for although this new evidence trended toward the health benefits of vegetarian and vegan practices, it was not identical to those diets. Vegetarians consume animal products like dairy and eggs, and some who identify as vegetarian even occasionally eat fish; vegans avoid all animal products, but their diets often include highly processed products made with refined carbohydrates, added fat, and excess salt; in contrast, our research suggested the benefits of a more wholesome dietary lifestyle with lower amounts of fat and more whole foods. The term whole food, plant-based reflects this nutrient composition far better than either of the V words.

Another reason for my reluctance to use those words is that vegetarianism (and, even more so, veganism) was a very contentious subject up through the early 1990s when our evidence was gaining a wider audience. I wanted to signal to skeptics that my scientific inquiries were driven by curiosity and research, not animal welfare concerns. During this time, the New York Times reported on our findings in a lead article in the science section, and several physicians (McDougall, Esselstyn, Ornish) reached out to tell me about their impressive findings with human patients, thus helping to corroborate our basic research.

(Learn more about the difference between the WFPB lifestyle and a vegan diet: What Is a Whole Food, Plant-Based Diet?)

Applying the Evidence

Choosing what to eat based on the evidence is a matter of personal choice. Although the evidence is certainly impressive, we need not exaggerate that evidence. I prefer not to say that any scientific investigation can give us absolute proof. Proof is too certain of a word. I prefer to evaluate scientific evidence based on its weight: how much evidence there is, how varied it is, how big the effects are, and whether it is relevant for humans.

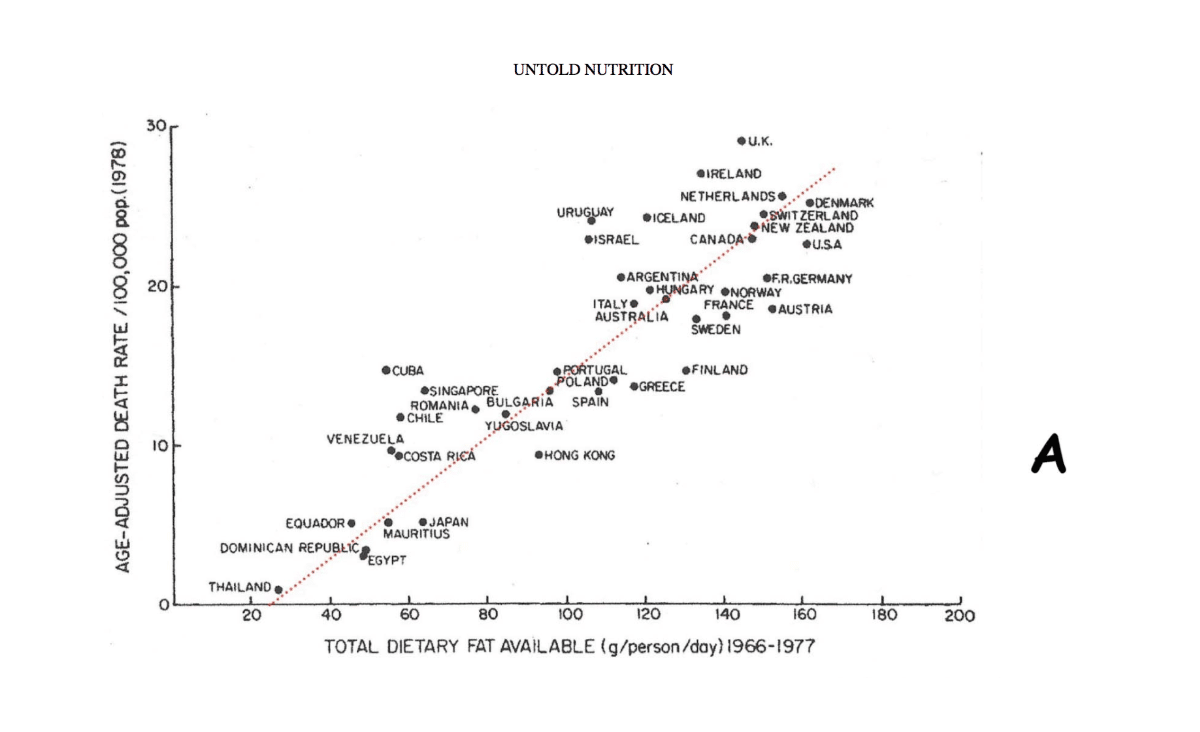

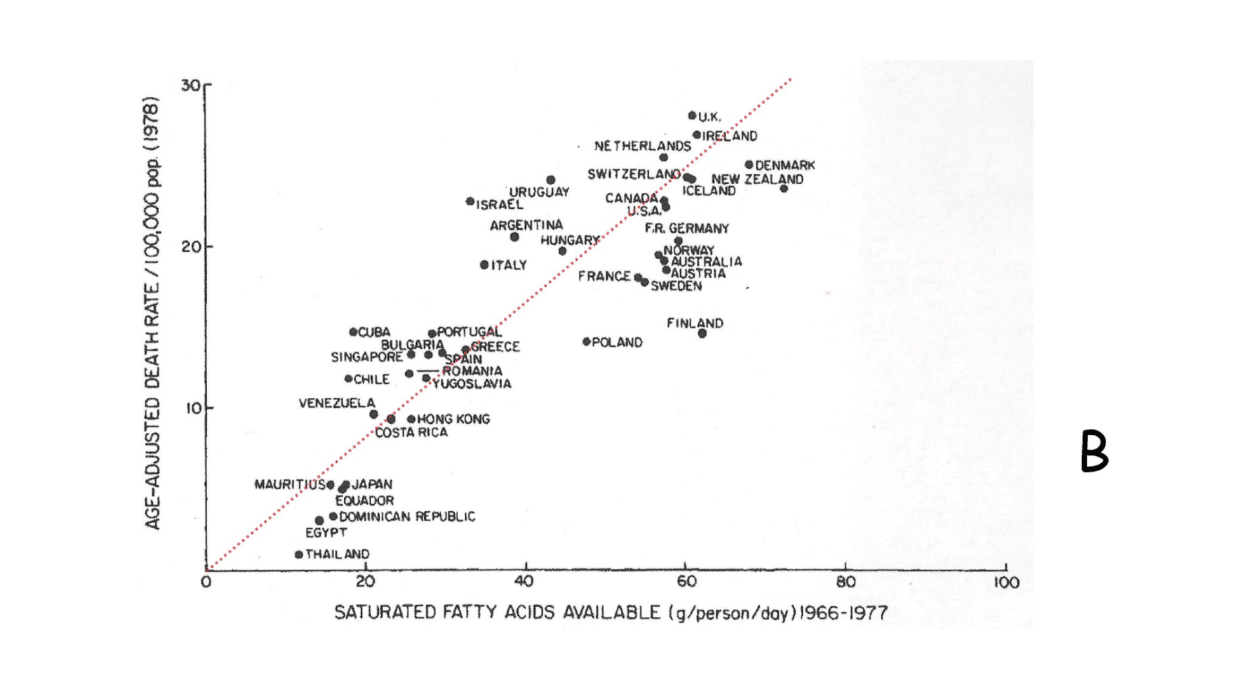

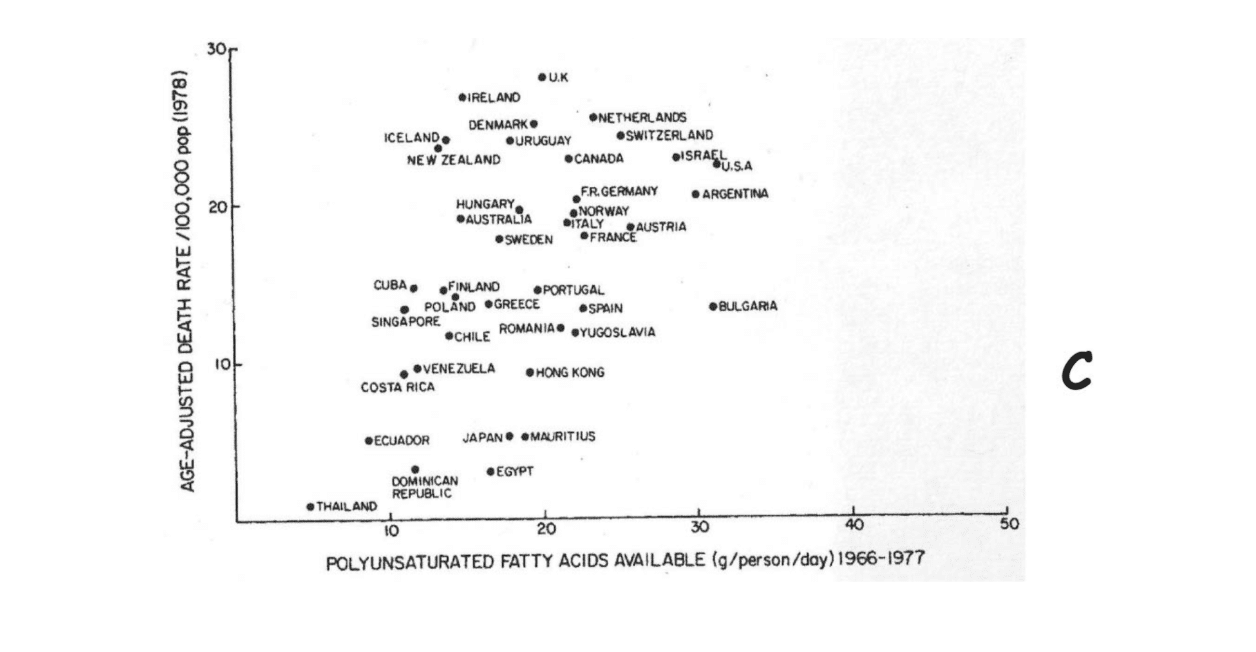

A wide, impressive variety of evidence supports my earlier statement that the closer we get to a WFPB lifestyle, the healthier we will be, but evidence is only ever supportive. The data below offer some supporting evidence for diets that approach a 100 percent plant-based composition. These charts show the association between breast cancer mortality and three kinds of dietary fat in various countries. In chart A, total fat (both animal and plant) is shown. Chart B shows saturated fat consumption, which comes mostly from animal-based foods. Chart C shows polyunsaturated fat consumption, which mostly comes from plant foods.[1] Notice the relationship between fat and breast cancer mortality in charts A and B and the lack of a relationship in chart C.

This seemingly suggests that the impressive correlation between total fat and breast cancer is due to saturated fat (typically provided by animal-based foods) rather than unsaturated fat (typically provided by plant-based foods). This information did not make a lot of sense when it was first published because there was also evidence showing that plant fat (i.e., oils) caused breast cancer to develop much more effectively than animal fat; however, this contradiction occurred only when total fat consumption was high, as is typical for Western diets!

Something more is needed: saturated fat and animal protein are highly correlated.[2] The relevant correlation is with animal-based foods. Notice also that the regression line in chart B for animal-based food passes through the origin (i.e., zero), thus suggesting that breast cancer risk increases even with minimal amounts of animal-based food. But this association is not only the effect of increased animal food intake: when animal-based food becomes a larger share of the diet, plant-based food simultaneously becomes a lesser share. Together, these changes, comprising countless nutrients, are associated with an increased risk of breast cancer and many other degenerative diseases. This still does not prove causality but is nonetheless supportive.

A similar case can be made with our China Project data, in which serum cholesterol ranged from 90–170 mg/dL; the lower end of this range would be considered extremely low. To illustrate, the typical range in the US is about 170–270 mg/dL. Our data indicated that even small increases in animal protein consumption in China were associated with increasing serum cholesterol. In reality, small amounts of animal-based food consumption in rural China are associated with increased risks for breast cancer and other Western diseases. The same is true with the US and other Western countries with a much higher range of serum cholesterol and animal protein consumption. In other words, the findings are consistent whether a population eats only small amounts of animal foods or a greater amount. The findings are particularly impressive when supported by multiple mechanisms explaining a powerful animal protein effect on cancer formation.

With benefits so broad and convincing with little or no downside, why would one not choose this diet?[3] Additionally, we now have data showing that intervention with this diet can produce broad, dramatic effects in a short period. That is not to say we have factual evidence that the WFPB diet always works for everyone and for all conditions. It is only, as I said above, a matter of weighing the evidence. Said another way, the odds of achieving health, both short- and long-term, with the WFPB lifestyle are so high that it seems foolish not to use it. This is especially true when we broaden our scope to include other considerations, such as environmental problems, health care costs, and unnecessary violence toward other sentient beings. The enslavement of animals on factory farms, as if animals are mere mechanical robots waiting for slaughter, is a far cry from my experiences growing up on a dairy farm, where our animals had names, green pastures, and personalities!

Nevertheless, I find it counterproductive to rely solely on ethical arguments for a WFPB diet. Strategies that involve trying to make other people feel unethical can easily backfire. Critically, trying to defend the ethical view by incorrectly saying that science has proven the health benefits of a 100 percent vegan diet is also a counterproductive approach. Much of the reluctance of my research colleagues to even be curious about this evidence relates to their belief that a WFPB dietary lifestyle is just a vegan diet in disguise. Many scientists are also understandably wary of claims about certain proof.

It is not that traditional scientists uniformly avoid or reject the ethical issues surrounding vegan and vegetarian practices, but these practices are not based on acceptable science. To some extent, I can understand these scientists’ concerns. When I browse the internet for information on vegetarian and vegan diets, I find far too much of it uninformed and superficial. It may be hearsay or not professionally published, it may lack primary referencing, or it may be biased by blatant commercial interests (e.g., supplement sales). What I am most concerned about, however, is the unwillingness to engage in discourse that challenges our views, and that goes for both plant-based enthusiasts and trained science professionals.

Good science involves being open to information that challenges one’s own views, as well as dominant institutional and cultural views. In the spirit of good science, I propose that we remain open to the numerous good reasons for choosing a WFPB lifestyle: environmental, financial, health, ethical, and more. Successfully advancing the case for WFPB nutrition will likely require a more comprehensive message. We have no reason to needlessly limit ourselves to only one point of view, especially if that viewpoint is based solely on personal values and absolutes.

References

- Armstrong, D. and R. Doll (1975). “Environmental factors and cancer incidence and mortality in different countries, with special reference to dietary practices.” Int. J. Cancer 15: 617-631.

- Campbell, T. C. and T. M. Campbell, II (2005). The China Study, Startling Implications for Diet, Weight Loss, and Long-Term Health. Dallas, TX, BenBella Books, Inc.

- Carroll, K. K. (1986). Experimental studies on dietary fat and cancer in relation to epidemiological data. Dietary Fat and Cancer. C. Ip, D. F. Birt, A. E. Rogers and C. Mettlin, Alan R. Liss, Inc.: 231-248.

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits