Superfoods are supposed to offer profound nutritional benefits. And they are marketed as such. The problem is that it’s not always clear whether the label is deserved because there is no accepted standard for what makes one food super and another merely healthy.

Moreover, it’s unclear whether this focus on individual foods is worth pursuing in the first place. The fact is that broader dietary patterns are much better predictors of health outcomes than the consumption of any one food, no matter how healthy it is.

Still, superfoods are mega-trendy. Google news search trends show a massive spike in searches for superfoods starting mid-2016; the number of web searches has generally been much higher throughout the past ten years than the six years before that.[1] “Superfoods” returns hundreds of millions of Google search results, many of which are focused on the exact same questions:

- What is a superfood?

- How many superfoods are there?

- How do we obtain superfoods?

- Which are the best superfoods for x illness (e.g., diabetes), or y life condition (e.g., expectant mothers)?

Much rarer are results questioning the premise, effectiveness, and potential dangers of this focus on superfoods. And that is worrying. Because even though many of the foods touted as “super” are healthy, our celebration of their miraculous properties might not be. In fact, I believe the focus on these foods often goes overboard, and I worry these attitudes have negative repercussions.

The popularity of this concept illustrates how marketing has come to dominate over nutrition. Is that worth preserving and encouraging? Do we prefer to approach something as critical as our health through marketing gimmicks? Can we not encourage healthy behavior in other ways?

But maybe that critique seems somewhat abstract and idealistic. Here are four specific reasons why a focus on superfoods is dangerous.

1. It creates endless opportunities to mislead the public about the healthfulness of certain foods.

Most published articles about superfoods are formatted as lists of superfoods. In these, each item is often accompanied by very little text. Maybe a short paragraph, often even less. These articles are easy to read and beautify with colorful, mouthwatering photos. Unfortunately, they do not offer adequate space to cover any food item in depth, meaning they’re also more susceptible to misleading information.

A few years ago, a Healthline article listed eggs as a superfood and described them more generally as “one of the healthiest foods.”[2] At a glance, the claim that eggs are a superfood seems hard to dispute:

Whole eggs are rich in many nutrients … [are] loaded with high-quality protein … contain potent antioxidants … known to protect vision and eye health … [and] despite fears surrounding egg consumption and high cholesterol, research indicates no measurable increase in heart disease or diabetes risk from eating up to 6–12 eggs per week … more research is needed to draw a definite conclusion [emphasis added].

There are many issues here to unpack.

First, without directly comparing eggs to any other food or combination of foods, the claim of nutrient richness is thin. Greater context is required. Many nutrient-dense foods also have unfavorable qualities, such as high cholesterol, fat, and animal protein. Shouldn’t these downsides figure into our calculation of whether a food is super or not?

Second, the claim that eggs are “loaded with high-quality protein” is provided with even less context. The article says nothing about how or why the protein of eggs should be regarded as higher quality than the protein of other foods. It says nothing about the history of measuring protein quality, which has long been biased toward animal protein without a convincing justification.[3] And even if the author wanted to, how could they elaborate on these subjects? Remember, this is just one item in a list of 16 superfoods; how much text can realistically be devoted to each item?

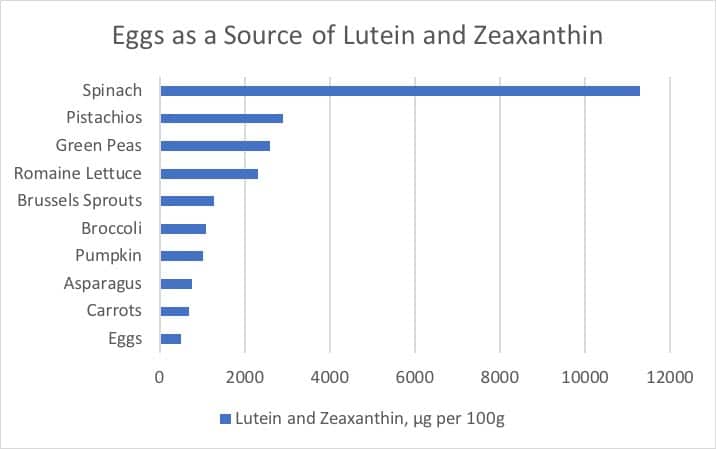

Third, and perhaps most misleadingly, is the mention of eggs’ antioxidant content, which is used to imply that eggs are uniquely good for eye health. Never mind that many foods provide far more antioxidants than eggs or that neither of the references in the Healthline article mentions eggs as especially good sources of these antioxidants. [4][5]

If it’s eye-healthy antioxidants you want, eggs don’t deserve a place on the table. Dark leafy green vegetables in particular are great sources of lutein and zeaxanthin, providing many orders of magnitude more of these antioxidants than eggs. Even non-leafy green vegetables provide much greater quantities of these antioxidants than eggs. The following chart includes only a couple leafy greens—there are many more containing large quantities of lutein and zeaxanthin—but play around with the MyFoodData database[6] and you can see how eggs stack up.

Source: MyFoodData; Reproduced from USDA Food Data Central

https://www.myfooddata.com (Accessed on 06 January 2021)

Fourth and finally, the article breezes by one of the most common concerns associated with egg consumption—its high cholesterol content—and “debunks” the concern by providing two “trusted sources,” both of which disclose authors’ connections to the animal foods industry. [7][8] This isn’t to say these researchers shouldn’t be taken seriously, but considering that none of the opposing research on the potential negative effects of egg consumption was discussed in any depth, I have to question the Healthline article’s claims.

Granted, all of these arguments for why eggs should be considered superfoods could be presented in any article format. But the formatting of superfood lists, which emphasizes brevity and style over substance and depth, makes them especially susceptible. It is not, in other words, that this information would not exist otherwise, but that the way we deliver information about superfoods encourages even more manipulation and cherry-picking.

2. It doesn’t do enough to provoke broad dietary change and might even encourage complacency by giving consumers a false sense of security.

Even in the case of legitimately healthful foods for which there is not a great deal of conflicting evidence—kale, for instance, is less controversial as a health food than eggs—an emphasis on superfoods might still have negative effects. People who don’t like kale shouldn’t feel pressured to eat it just because it’s trendy. Bok choy might not top as many lists of superfoods, but that’s okay—we should lean toward the healthy foods we most enjoy, and enjoy their variety, not bend to the popularity of single food items.

More importantly, by focusing on individual foods, we may be more inclined to look for “magic bullets” rather than sweeping change. Most Americans’ diets require a far more substantial change than the introduction of a few foods. Our outsized focus on those foods doesn’t encourage that substantial change and might give people a false sense of security (i.e., I got my daily dose of turmeric and blueberries—covered my bases!) Of course, if we enjoy turmeric and blueberries and want to integrate them into a whole food, plant-based (WFPB) diet, that’s great. But we should be wary of thinking about them as supplements.

3. It contributes to our society’s distorted perception of how much it costs to be healthy.

There is a widely held misconception that healthy eating is difficult to achieve on the average budget. It is a myth that ignores several costs associated with food—especially the costliness of disease and the cheapness of healthy staples (foods like sweet potatoes, legumes, and whole grains).

Once again, our focus on superfoods might make this condition worse.

That’s because many foods labeled as “super” are expensive and difficult to find. That does not mean they aren’t healthy, but as long as we want healthy living to be accessible to everybody, we should avoid placing too much emphasis on exotic products like cordyceps mushrooms, maqui berries, and maca powder.

You might personally decide to enjoy the unique health benefits of these foods. Fair enough. Just remember that the extraordinary effects of broad dietary change that incorporates a wide range of affordable foods are much more impressive.

This point is even more important on a societal, communal, or even familial level. It’s trickier to budget for foods like acai berry powder than for foods like purple cabbage. We should be encouraging not only sweeping dietary change but also a sweeping change in how “normal” people view the cost of health.

Too often, superfoods encourage the opposite perspective. They epitomize a consumer-producer relationship that is off-limits to most people, such that “their consumption is seen as the expression of the endeavor to achieve a healthy, wealthy and long life, and thus social distinction.”[9] In other words, marketers are not only selling “health,” but also a feeling of superiority and elitism.

Well-meaning consumers should not be blamed for that. Who wouldn’t want to eat the healthiest food available? Even if only for the extra sense of protection and peace of mind. Nevertheless, these attitudes have secondary effects, and they can be damaging to how we view health, especially to less-prosperous consumers.

4. It has environmental and social repercussions often unseen by consumers.

In an article published in People and Nature, researchers explore how surging demand for superfoods can impact the people and ecosystems where those foods are produced.[10] Through a series of case studies, they link superfood commodification to:

- the erosion of local food systems,

- the damaging spread of monocropping,

- decreased genetic diversity of plant life,

- a boom-or-bust economic cycle that leaves farmers and communities more vulnerable to the whims of distant consumers,

- increased greenhouse gas emissions,

- the increased use of agrochemicals, and

- unsustainable land clearing.

For example, when demand for quinoa peaked around 2006–2013, farmers responded by departing from more sustainable traditional harvesting practices. [11] “The demand for quinoa was focused on only a few of the over 3,000 different varieties [. . . prompting] farmers to abandon many of these varieties.” And when the cost of quinoa plummeted, those economies were in a much worse position than they had been before. “According to a study conducted on Bolivian farmers of quinoa, more than half said the quality of their soil has worsened.”

And again, this is not to say that quinoa should be avoided. Nor is the point to condemn unwitting, health-seeking consumers that fuel demand. Nevertheless, it illustrates the unintended effects that can accompany the mass commodification of healthy food.

But wait—aren’t there benefits?

You might wonder: if more people are eating kale and goji berries because of the thousands of articles citing kale and goji berries as superfoods, then isn’t that enough of a benefit to outweigh the concerns listed above?

Maybe, but let’s not forget—there are many other ways to encourage the consumption of kale and goji berries free of the baggage listed above. For instance, we could better share the body of evidence supporting a WFPB diet, which encourages the consumption of diverse plant foods without getting caught up on any individual food item. We could nurture and protect the healthy foods that grow where we live. We could better train health professionals in nutrition. We could advocate for numerous changes to limit the industry’s influence over national food policy.

These might not be the sexiest, most clickable, or most profitable suggestions. In many ways, they are the opposite. But is that so bad? We have given marketing and profit a turn; for decades, we have given things like sexy, clickable superfoods a lot of attention. How has it helped our health?

This article is part of a series on The Future of Nutrition: An Insider’s Look at the Science, Why We Keep Getting It Wrong, and How to Start Getting It Right by T. Colin Campbell, PhD, (with Nelson Disla) released December 2020.

Read more articles in the “Future of Nutrition” series from Dr. T. Colin Campbell and Nelson Disla:

Healthcare vs Disease Response System – Part 1

Healthcare vs Disease Response System – Part 2

Is it Time to Quit the “War on Cancer”?

How Much Does Malnutrition Really Cost?

References

- Google Trends. Superfoods. Online access: January 6, 2021.

- Hill, A. 16 superfoods that are worthy of the title. Healthline (2018). https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/true-superfoods

- Campbell, T. C. The cult of animal protein. The Future of Nutrition: An Insider’s Look at the Science, Why We Keep Getting it Wrong, and How to Start Getting it Right (2020).

- Delcourt C., Carriere I., Delage M., Barberger-Gateau P., Schalch W.; POLA Study Group. Plasma lutein and zeaxanthin and other carotenoids as modifiable risk factors for age-related maculopathy and cataract: the POLA study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47(6) 2329–35 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.05-1235

- Gale C. R., Hall N. F., Phillips D. I., Martyn C. N. Lutein and zeaxanthin status and risk of age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 44(6) 2461–5 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.02-0929

- MyFoodData. Online access: January 6, 2021. https://www.myfooddata.com

- Richard, C., Cristall, L., Fleming, E., Lewis, E. D., Ricupero, M., Jacobs, R. L., Field, C. J. Impact of egg consumption on cardiovascular risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes and at risk for developing diabetes: a systematic review of randomized nutritional intervention studies. Canadian Journal of Diabetes 41(4)2 453–463 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjd.2016.12.002

- Blesso, C. N., Fernandez, M. L. Dietary cholesterol, serum lipids, and heart disease: are eggs working for or against you? Nutrients 10(4) 426 (2018). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10040426

- MacGregor, C., Petersen, A., Parker, C. Promoting a healthier, younger, you: the media marketing of anti-ageing superfoods. Journal of Consumer Culture (2018) https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540518773825

- Magrach A, Sanz MJ. Environmental and social consequences of the increase in the demand for ‘superfoods’ world-wide. People and Nature 2(2):267-278 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10085

- Lu K. The problem with superfoods: for you and the world. Study Breaks. April 24, 2021. Accessed March 13, 2023. https://studybreaks.com/thoughts/the-problem-with-superfoods/

Copyright 2026 Center for Nutrition Studies. All rights reserved.

Deepen Your Knowledge With Our

Plant-Based Nutrition

Certificate

Plant-Based Nutrition Certificate

- 23,000+ students

- 100% online, learn at your own pace

- No prerequisites

- Continuing education credits